U.S. cities don't know nearly enough about how many people are biking — and until they harness the power of big data and static counters, they could remain in the dark about how to best support some of the most vulnerable users on the road, a new study argues.

In a recent paper for the National Institute for Transportation and Communities, researchers took a close look at the shockingly nascent science of bicycle counting and how cities could do a better job of measuring where its residents ride.

Countless American cities have invested in networks of car counters, whose infamous "level of service" data transportation leaders often use to justify dubious lane expansion projects on the busiest segments of their road networks. Far fewer U.S. communities, though, have invested in comprehensive physical or digital methods of counting people on two wheels, with many relying on little more than an annual paper-and-pen bike count conducted by volunteers, if they bother to count at all. That means that dynamic changes in ridership caused by easily fixable problems can go totally unnoticed until a resident makes a report — and even basic, critical metrics, like how likely pedestrians are to be killed in a fatal crash per miles traveled, aren't analyzed at all.

With so little data on where (and even whether) people are riding, bike-focused infrastructure can all too easily be put on the back burner, as sky-high automobile counts bump car-focused projects to the top of the priority list.

"These estimates have been available for decades on the motorized side, but they’ve only become feasible in the last decade or so on the non-motorized side," said Sirisha Kothuri, senior research associate at Portland State University and the lead author of the paper. "But we've always needed these network-wide estimates of bicycle volumes because they are really important for evaluating the safety, equity, health, and climate of our road networks."

To get a sense of how to build a better bike counting program, Kothuri and her team pored over data from six cities — Boulder, Charlotte, Dallas, plus the Oregon cities of Portland, Bend and Eugene — that run the gamut between urban bike Meccas and suburban communities with relatively little cycling infrastructure or tools to count riders.

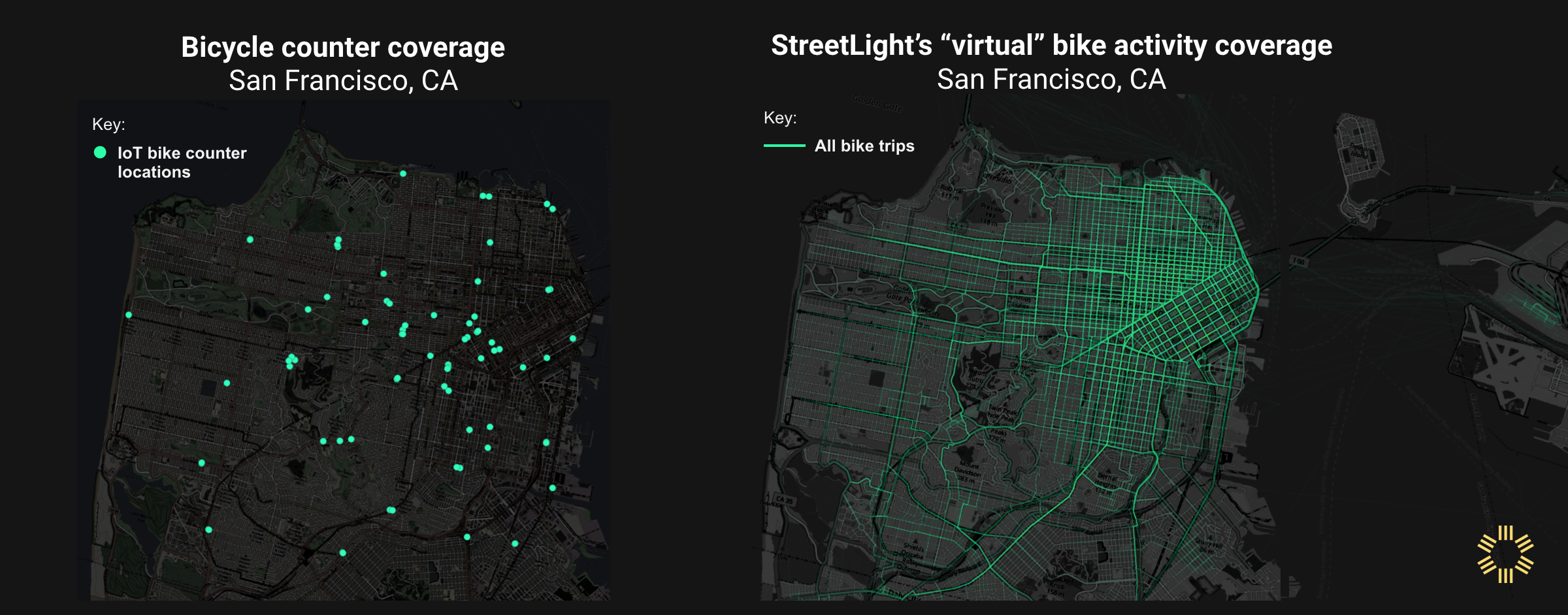

Unlike previous studies, the data included both physical counters that automatically sense when a person on two wheels is rolling by a specific location, as well as more diffuse data from bikeshare providers, voluntary ride-tracking app Strava, and the Big Data company Streetlight, which uses anonymized cell phone data to automatically sense how many people are pedaling through an entire region in real time. (And Streetfilms auteur Clarence Eckson Jr. has his own method.)

All of those data sources are valuable, but Kothuri emphasizes that none of them alone provides an accurate picture of what biking looks like American cities. Physical counters are expensive, often stop transmitting data when they need maintenance, and tend to be clustered in highly trafficked city centers rather than everywhere a cyclist might ride. Strava, meanwhile, tends to be used by recreational riders who travel far outside the core downtown, while bikeshare data, particularly for docked systems, obviously skews towards routes near hubs where people are most likely to pick up and return their vehicles.

Even big data company Streetlight can't capture data from the 15 percent of Americans who don't have smartphones, and the researchers say they may overcount bicyclists at some locations — like along a traffic-choked transit route where bus riders are going about the same speed as a cyclist — while undercounting them at others, such as along busy bike boulevards where anonymized riders' signals get mixed up with one another. The researchers found that "using Strava or StreetLight counts to predict annual average daily bicycle traffic without static adjustment variables [from physical counters] increased expected prediction error by a factor of about 1.4."

"We need counters pretty much everywhere; they’re giving us our best representation of street-level ground truth," said Kothuri. "At the same time, we want estimates across the entire network, and in many places, the physical counters we have can't give us that."

To get the most accurate possible bicycle traffic forecast, Kothuri and her team developed a "pooled" model that synthesizes data from every available traffic source across the six cities — though she cautions that creating a bespoke, city-specific model using a similar methodology would yield the most accurate predictions, and that local leaders should consult her paper for tips on how to do it right.

Even city leaders without a top-flight environmental engineer on staff, though, could still be doing a better job of measuring its vulnerable road user activity. Kothuri particularly recommends that policymakers go after any available grant money they can find to invest in automatic bicycle counters in addition to big data services, validate and maintain those static counters rigorously, and place them thoughtfully throughout the community, not just on the recreational trails where counters are most likely to record big numbers. (NACTO recently released a great guide to bike counter siting, among other considerations.) Standardizing the format in which data is collected could also go a long way towards helping cities build meaningful models that they can use to make informed infrastructure decisions fast.

However they approach the problem, though, Kothuri emphasizes that cities shouldn't let a lack of resources be an excuse not to do start counting bikes however they can — and taking steps to make those tallies as accurate as they can be.

"We really need to count bicyclists and pedestrians," she adds. "They are active users of our system, and they’re also the most vulnerable. We need them to improve conditions for them, and frankly, when we do it, we improve conditions for everybody. We did it for motorists; now let's do it for everyone else."