Despite decades of increases in car ownership, it still takes Black workers 22.4 minutes longer to get to work every week than their White counterparts, according to a new study, suggesting it may not be possible to speed up city commutes with automotive strategies alone.

Researchers for the Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia examined how commute times have shifted as America grew increasingly car dependent over the last 40 years, and how those shifts varied across racial demographics.

As previous research has shown, Black commuters in the U.S. have pretty much always had the longest commutes of any group, averaging 26 minutes each way back in 1980 when census-takers first began asking U.S. residents how long it took them to get to to work. That was five minutes longer than their White counterparts' average journeys to work that year, or about 50 lost minutes every single week — a difference that the researchers attribute in large part to the fact that Black road users were (and still are) significantly more likely to rely on shared and active modes, neither of which are given the resources necessary to get people where they need to go conveniently.

That small time difference, by the way, makes a big difference when it comes to quality of life. A 2017 study from the University of West Bristol found that "every extra minute of commute time reduces job satisfaction, reduces leisure time satisfaction, increases strain and reduces mental health," and that those downsides compound when a worker's job is too far away way to walk. And because the Census still doesn't collect data on how long it takes Americans to get anywhere besides work, these stats don't even give a full picture of the delays that Black travelers face when navigating their communities when they're off the clock.

At least at first glance, that might seem like a good argument for subsidizing private vehicle ownership among Black commuters, as some non-profits have done for low-income families, sometimes to positive effect. And that's essentially what America did over the next 40 years — not by directly buying vehicles for under-resourced groups, but by subsidizing car ownership overall in a myriad of well-documented ways.

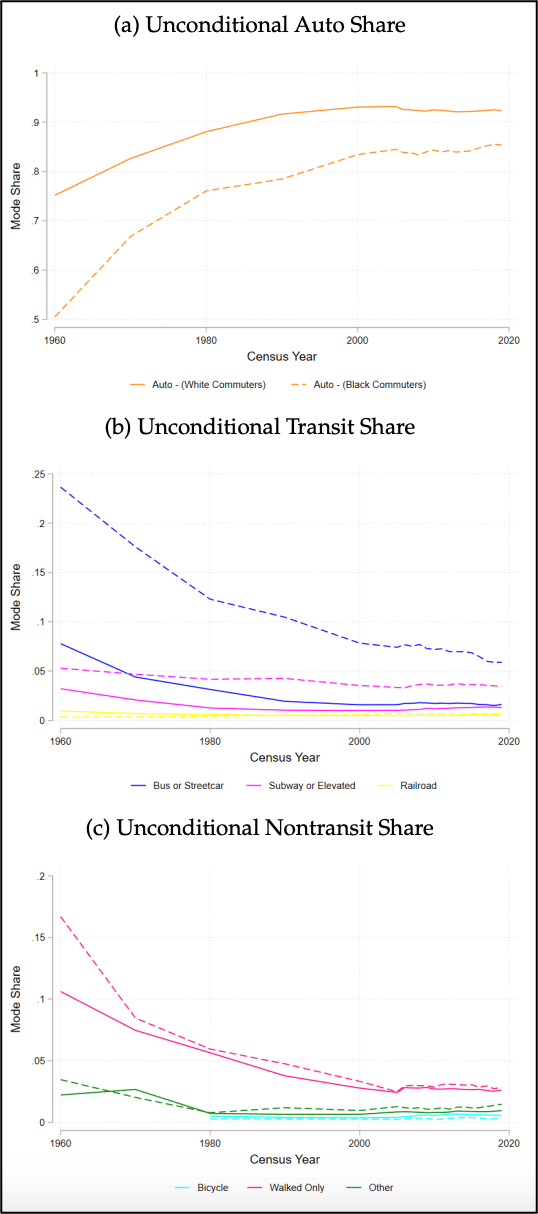

Indeed, by 2019, a staggering 85 percent of Black U.S. residents were climbing behind the wheel every day they punched a clock, up from 76 percent in 1980 (and just 50 percent in 1960, by the way). While that happened, though, average commute times actually got longer, rising to 28 minutes each way — a 7-percent bump in 40 years. (White workers spent a little more time in rush hour, too — 26 minutes, or a 19-percent spike — even as their car usage soared from 88 percent of all workers in 1980 to 92 percent in 2019.)

The upside of those damning numbers, of course, is that the gap between Black and White commuters' average travel time has shrunk over the past four decades — though the researchers were careful to note that it didn't happen everywhere.

As Black and white workers saw their commute times roughly equalize in small- and mid-sized cities — particularly those with lots of freeways — the discrepancy actually got wider in big metros, even as Black workers gained access to opportunities that should have put more commuting and housing options within their reach.

"In some cities — large, segregated, and congested or transit-dependent — a car may be insufficient to ensure a fast commute," the researchers wrote. "Further, high land costs may price a car (and parking) beyond the reach of many households."

The rising price of housing itself is also keeping trip times long, even for Black workers who do drive — especially in highly segregated big cities where they can't find homes anywhere near their jobs. The study authors estimated that if all cities' home prices had been frozen in 1980, the difference between Black and White workers' trip times would have been roughly halved, even if employment centers migrated.

"Job growth is often concentrated in particular suburbs that may not overlap with the suburbanization of communities of color," the researchers added. "Indeed, the two may be on opposite ends of the city, as in Dallas-Fort Worth or Washington, D.C."

Of course, when enough workers are forced to cross town in a car to earn a paycheck, commute times swell even more — because everyone ends up stuck in traffic.

"Large and congested cities may be relatively impervious to car-based convergence," the researchers wrote. "High land prices make cars expensive and slow travel speeds transform extant racial and employment segregation into a racialized commute differential."

Put another way: unless big cities end housing and employment segregation, no amount of driving subsidy can meaningfully speed up Black workers' commutes, even if we can someday close the gap among workers' driving times by sticking everyone in giant traffic jams. Subsidizing driving any more than we already do, though, will make streets incalculably more polluted and dangerous — and both burdens will almost certainly fall on communities of color where the dirtiest and deadliest thoroughfares are disproportionately located.

There are better ways to erase these racialized commute time differences, of course: by building bus rapid transit and trains, removing the unique barriers to active transportation faced by people of color, and building communities where jobs, housing, and essential services are located within sustainable commuting distance — all while supporting robust policies that makes sure Black residents can live, work, thrive, and feel at home in these people-centered neighborhoods. And until we change our approach, a lot of folks will be left behind.