Street safety advocates, government leaders and cannabis industry reps are banding together to ask drivers to please not drive under the influence of marijuana — but advocates question whether it will have enough of an impact if the nation does not undertake systemic change that gives residents other options to get around when they've been hanging out with the Doobie Brothers.

Representatives from Mothers Against Drunk Driving Colorado joined with state transportation leaders, police, and cannabis professionals on Wednesday to urge drivers to take a voluntary "safe driving pledge" ahead of the unofficial "420" holiday next week. Colorado dispensaries typically report a 48-percent sales spike in the days before April 20, which enthusiasts have long treated as an international celebration of all things reefer-related for a bunch of vague reasons that have become the stuff of urban legends.

What's decidedly not vague, though, is the anguish of Coloradans whose loved ones were killed by impaired drivers, who were implicated in 37 percent of the Centennial State's roadway fatalities last year. Toxicology screening for THC can be a challenge — more on that later — but 52 percent of the 6,071 drunk drivers whom the state tested for cannabinoid compounds in 2019 returned positive results.

The coalition is hoping that its public service announcements will help reverse that trend, despite a disappointing World Health Association analysis that found drunk driving education campaigns do not definitively reduce fatalities — and scant evidence that pot-focused campaigns will be any different.

Small's recommendation that marijuana users "plan ahead for a safe ride home" was echoed by the other members of the panel, who emphasized automotive solutions like taxis or relying on friends with cars to get around when they're high.

Signifcantly less airtime, though, was given to keeping cannabis customers out of cars at all — much less the formidable task of giving them meaningful access to active and shared transportation on dangerous Colorado roads. About 75 percent of Coloradans currently drive to work alone, a metric that experts consider a rough proxy for overall travel behaviors — and even in highly urbanized and dispensary-rich Denver, that ratio holds true for all but the most transit-rich neighborhoods.

"We're all against impaired driving, but if we're going to be against impaired driving, we need to rethink our whole system," said Skylar McKinley, regional director of public affairs for AAA Colorado, in the last 10 minutes of the event. "We have built our entire society around the car. And if we want to get serious about solving this, we need to ... make transit appealing to people who get drunk and high. What can we do to make it safe to walk home from your friend's house, or walk home from the bar?"

Why pot is so hard to spot

The omission of those strategies is particularly strange considering the inherent challenges of detecting THC intoxication behind the wheel — and how few solutions are in sight.

Despite being legal for either recreational or medicinal use in 40 states — and a lot of emerging evidence that stoned driving is a road safety problem, at least in combination with alcohol — policymakers have struggled to develop a meaningful threshold for THC intoxication behind the wheel. Unlike alcohol, no roadside detection device for cannabis currently exists, and THC can often be found in the blood and saliva up to 36 hours after consumption, long after any cannabinoids may have lost their effect — and it stays in the urine and hair even longer.

Moreover, those effects can vary wildly from user to user, depending on the amount of weed he or she habitually consumes — a particular problem among daily medical users — the potency of the user's preferred strains, height and bodyweight, and even what food the smoker ate that day.

Colorado legally allows drivers to have up to five nanograms of THC in their bloodstream behind the wheel, but experts say that number is troublingly arbitrary. A 2016 AAA study found that nanogram levels bore almost no relation to drivers' actual ability to perform on standardized field sobriety tests, concluding that "a quantitative threshold for per se laws for THC following cannabis use cannot be scientifically supported."

In the absence of a meaningful legal threshold, law enforcement officers rely on field sobriety tests to estimate a drivers' unique level of impairment — though some advocates argue that any programs that increase contact between officers and the public are unacceptable, given the well-documented dangers such encounters can pose to people of color.

Moreover, studies have shown that basic walk-and-turn tests common in drunk driving stops aren't even good at determining whether a driver is too high to get behind the wheel. More comprehensive and accurate field evaluations, like those performed by police certified as Drug Recognition Experts, are still being conducted by police, rather than scientists or doctors — a fact that has lead at least one judge to dismiss the DRE program as "are not based on science."

And even when judges don't dismiss testimony from Drug Recognition Experts, that doesn't mean they always have the opinion of one ready at hand when they prosecute impaired drivers. The entirety of Colorado has just 168 officers certified under the program, and they're patrolling a state with more than 183,000 miles of roads.

Inherently hostile streets

The good news, of course, is that Colorado and every pot-friendly state like it has a model for how to end cannabis-related road deaths: the notoriously bike-friendly (and blunt-friendly) Holland.

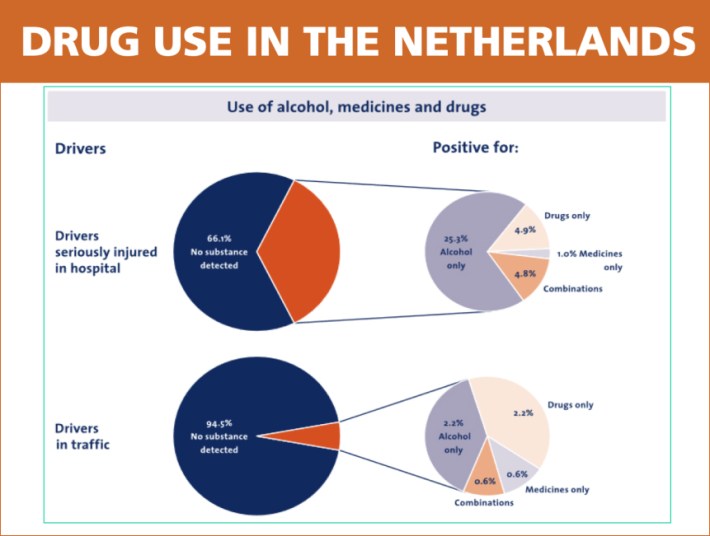

A 2012 study found that only 0.5 of Dutch drivers who had been seriously injured in crashes tested positive for THC, compared to 8 percent of drivers in Belgium — even though the Dutch sample included more risky young male drivers and four times as many drivers who admitted to using cannabis regularly when not behind the wheel.

The reason why, researchers say, probably boils down to the fact that the Dutch simply drive — and crash — a lot less than the Belgians, who have a 42 percent higher per-capita road death rate than their lowland neighbors. Moreover, that study was conducted five years before Holland specified a legal threshold for stoned driving and upped DUI penalties, to harsh criticism from cannabis industry reps.

For AAA Colorado's Skyler McKinley, though, simply emphasizing the need for safe systems isn't enough. Also a veteran of the state's Office of Marijuana Coordination, he says he thinks every state considering legalization should take steps now to make sure they're giving stoners a safe way to get home — by investing marijuana taxes into Vision Zero funds.

"If the goal of these conversations is to save lives, we would be remiss not to say, 'Maybe we should be looking at the automobile,'" he added in a follow-up interview with Streetsblog. "Cannabis predates the automobile, but we treat driving [dependency] as the thing that's not going to change. ... You won't hear a lot of cannabis or alcohol companies advocating for transportation reform, and that's something I'd love to see change."

McKinley adds that private and public intervention is particularly critical when it comes to marijuana users, who have no supervised public space to consume their preferred intoxicant, and thus no trained bartender (or budtender) to take away their keys. And he also adds that making the world safe for stoners (to adapt a famous saying from epidemiologist Susan P. Baker) would help drunk travelers, too — and sober people who struggle to navigate dangerous roads even with all their wits about them.

"Whether you're drunk, high, or sober as a judge, we have a lot of hostile cues in our built infrastructure that makes walking unappealing, dangerous and difficult," added McKinley in a follow up interview with Streetsblog. "If you want to encourage people to make the safe transportation choice, you have to address that."