A top intergovernmental organization released a 10-point plan to cut gasoline use worldwide in response to Russia's invasion of Ukraine, which the group says will put the planet on track to meet its broader emissions-reduction goals — but the U.S. will have trouble actually implementing it without an upheaval on our national transportation culture.

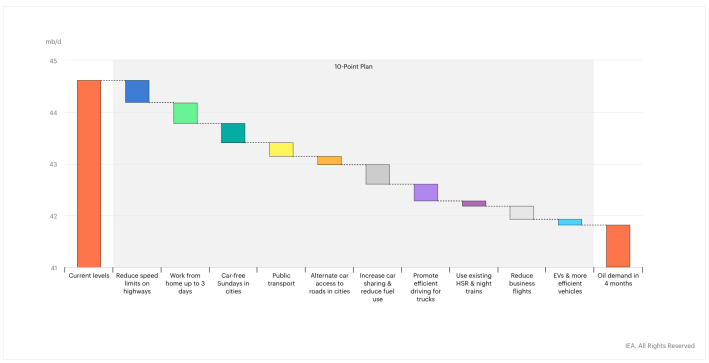

Last week, the International Energy Agency urged government leaders to implement a raft of emergency strategies that will immediately ease pain at the pump by getting residents to pass on gasoline entirely — all without sacrificing their basic mobility. Those ideas, collectively, would reduce oil demand by 2.7 million barrels every day if deployed across the organization's 31 member states and eight associated countries, a list which includes the United States. (Context: The world consumes close to 100 million barrels of oil every day.)

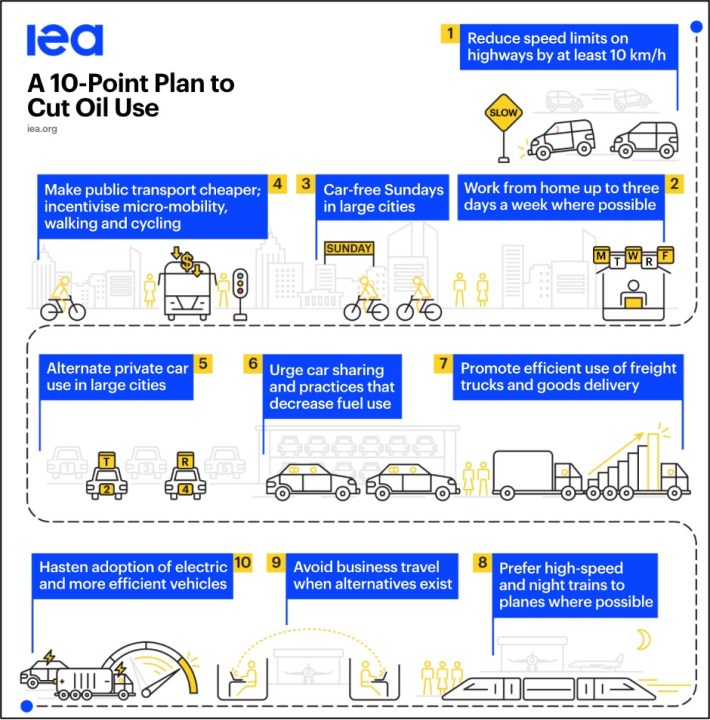

Notably, all but one of the Agency's recommendations were aimed at reducing car usage or vehicle speeds, with hastening electric and efficient vehicle adoption landing last on the list.

The most impactful suggestions, meanwhile, all focused on getting vehicles off the road entirely, including:

- Increasing remote work (500k barrels/day if everyone who possibly can skips their commute just three days a week),

- Carpooling (which would save 470k barrels/day, especially if drivers turned off the air conditioning and monitor their tire pressure), and,

- Instituting car-free Sundays in urban areas (380k/barrels for every day without private vehicle traffic, with a handful common-sense exemptions, such as emergency services vehicles, delivery trucks, and cars used as mobility aids)

The list stands in stark contrast to many U.S. lawmakers' recommended responses to the ongoing fuel crisis, which have largely emphasized increasing oil supply with additional drilling and artificially decreasing fuel prices by temporarily eliminating federal and state gas taxes.

Most experts seem to agree, though, that neither strategy will lower oil prices very much. New domestic oil leases will take years to actually generate new supply, and road user fees like gas taxes are already so low — and subsidized so heavily by general funds — that even eliminating them outright would barely make a dent.

"A gas tax holiday might help consumers in the short run, but by further cementing our dependence on fossil fuel-fired cars, it will only leave Americans even more vulnerable to the next crisis," said Matthew Casale, environment campaigns director at the U.S. Public Interest Research Group.

Casale supports the International Energy Agency's emphasis on demand-side solutions to the current fuel price crisis, which advocates have pointed out is only a crisis at all because America depends so heavily on private automobiles (which have gotten larger), rather than on a broad range of low- or no-fuel mobility options.

Getting American communities to actually try those solutions, though, won't be easy without dramatically rethinking the country's core transportation structure and culture first. And some suggestions on the agency's list, like pushing commuters towards high-speed trains over fuel-intensive plane travel, simply aren't possible, because America functionally has no high-speed rail at all.

"If we had been doing these things all along, we wouldn't be in this mess in the first place," Casale added. "But in the U.S., we're not geared towards these kinds of proposals....Reducing demand just isn't the focus of the conversation on either side of the political aisle, but it needs to be."

To make sure that America is insulated against future crises, Casale says it's critical that the country rethink how we pay for transportation overall — and particularly, how much drivers pay for their impacts on society. U.S. PIRG recently released its own multi-point plan to fix America's transportation financing systems, which the group says would make it all but impossible for communities to justify building car-focused mobility networks.

In the meantime, short-term strategies like reducing highway speed limits and providing incentives for fuel-free travel can work — and they're the least we can do to confront the far larger challenges of climate change.

"The IEA's 10-point plan would be a good start, and would help alleviate many immediate problems," added Casale. "But to ensure this leads to a longer-term fix, we need to reform our entire system of pricing and paying for transportation so that the cheapest and most convenient modes of transportation are also the cleanest, healthiest, safest, and most efficient."