Utah cut alcohol-involved crashes nearly 9 percent in a single year after adopting the lowest threshold for drunk driving in the nation, a new study finds — but better transit might deserve a little credit, too.

On Feb. 1, the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration released a new analysis of the Beehive State's new DUI law, which dropped the threshold for drunk driving from 0.08 grams of alcohol per deciliter of blood to just 0.05 g/dl in 2019.

Utah already had some of the lowest rates of drunk driving crashes in the country, thanks in part to the fact that 60 percent of the population belongs to the Church of Latter Day States, which forbids alcohol consumption — but those who do drink are more likely to binge drink than the US population at large.

After Utah instituted the new limits, though, drunk-driving crashes dove a further 8.9 percent below what the team projected they would have been without the change, based on the previous 12 months — and the percentage of drivers on the road who tested above the new legal limit fell 22.5 percent.

Maybe the most remarkable thing about Utah's new law is that it's seen as remarkable at all — at least in contrast to the rest of America's permissive DUI policies.

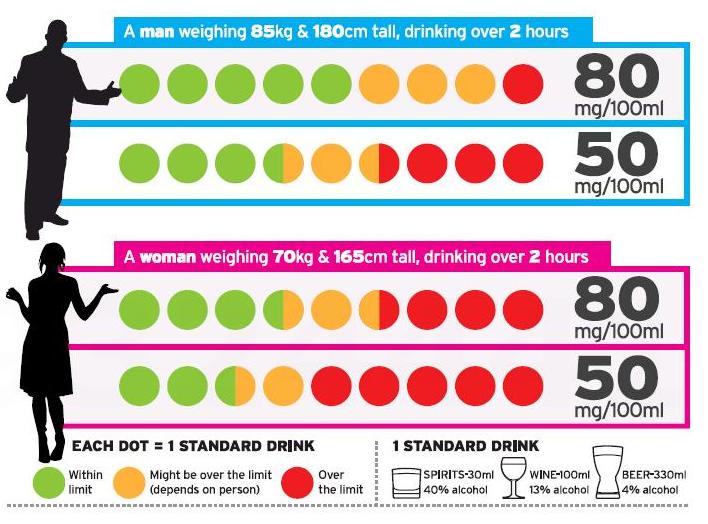

After all, it typically takes a lot of drinking to get to a blood alcohol content of .05, which researchers say roughly equates to a 185-pound man drinking four alcoholic beverages on an empty stomach over a two-hour period, or a 154-pound woman having three drinks, give or take differences in that driver's age and metabolism rate. Decades of studies have shown that drivers who blow a 0.05 are 1.38 times more likely to be involved in a collision than a sober motorist — and drivers who blow an 0.08, the threshold in every other state in America, are 2.69 times more likely to crash.

Setting a sensible alcohol limit, though, isn't the same thing as getting drivers to actually follow it — and NHTSA struggled to identify exactly why Utah's law worked so well. The agency noted that the state barely publicized the policy shift, save a brief FAQ page and a single video that emphasized that law enforcement would treat the new law as "business as usual;" it had been viewed by just 451 people at the time of this article's publication.

Researchers noted that the state did not launch a major public awareness campaign about the new limits, and police didn't arrest significantly more drivers for DUI in 2019 than in previous years. In a 2019 survey, only 54 percent of respondents who drank even knew about the new law, though that was up significantly from how many knew about the old threshold in 2018 (31 percent.)

Moreover, NHTSA didn't explore the impact of less conventional DUI countermeasures, like improving access to high-quality transit as an alternative to driving. Utah did just that in the years before the new law went into effect, adding bus rapid transit lanes, increasing service frequency, and beginning in 2019 — the same year the new law went into effect — offering free transit to many of the state's college students under a federal grant.

That year, bus ridership through the Utah Transit Authority increased 8.2 percent statewide, reversing years of steady declines.

NHTSA also wasn't able to analyze the impact of biking, walking, micromobility, and other sustainable transportation on DUI rates for 2019, because data on those modes isn't regularly collected.

Those gaps in NHTSA's analysis might also explain why Utah's law succeeded while similarly stringent laws in other communities failed.

Last year, researchers in the United Kingdom found that when Scotland dropped its own DUI threshold to 0.05 BAC, alcohol-involved crashes and the rates of drunk driving overall did not improve.

The study authors concluded that was, in part, because the country poured its money into educational campaigns rather than increasing access to transit, taxis, carpool, and other mobility options. Just like Utah, survey respondents were more likely to indicate that they'd changed their driving behavior in response to the new limits, but the Scots didn't actually do it.

“When the law changes, people need an alternative way to get to the bars or the pubs,” Jonathan James, senior lecturer of economics at the University of Bath and co-author of the paper, told Streetsblog. “Most of the international evidence we have tends to suggests that changing drink-driving limits alone doesn’t do much if you don’t do that.”

At the time, James also pointed out that Scotland hadn't put additional resources towards enforcing the new law, like adding more police patrols and DUI check-points — though Utah didn't, either, and it drunk driving metrics did improve. That could suggest that fear of increased enforcement wasn't the missing ingredient in Scotland's strategy after all, nor was it a driving factor in driving down Utah's DUI stats.

If other states follow Utah's lead and adopt lower limits — which, to be clear, they absolutely should — lawmakers would be wise to analyze the impact of those policies in the broader context of their entire transportation culture, including how easy it is for their residents to get home from the bar on the bus.