Sometimes you wonder why the federal government even bothers.

After the Biden administration told states that they should spend federal transportation dollars on projects that put safety, sustainability, equity, and road repair first, two top Republican senators have told GOP governors to ignore the guidelines and spend the money any way they want.

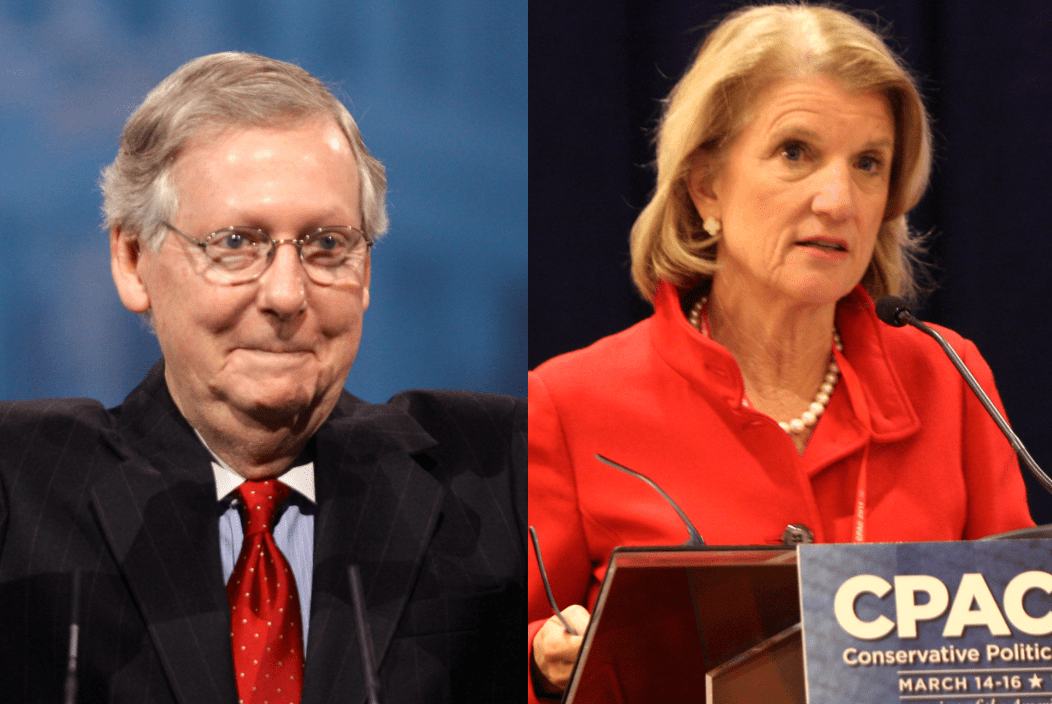

On Feb. 9, Senate Republican Leader Mitch McConnell (R-Ky.) and Senator Shelley Moore Capito (R-W. Va) issued a memo to 16 GOP governors who had slammed the US DOT's recent commitment to prioritizing sustainability, equity and multimodal safety in its grant-making processes as "an attempt to push a social agenda through hard infrastructure investments."

But don't worry about the federal initiative said the anti-federal initiative McConnell and Capito, who told the governors they can still embark on highway-building free-for-alls.

"Nothing in the [Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act] provides FHWA with the authority to dictate how states should use their federal formula funding, nor prioritizes public transit or bike paths over new roads and bridges." they wrote. "The FHWA memorandum is an internal document, has no effect of law, and states should treat it as such."

Some advocates, though, think US DOT's guidelines might be stronger than the senators think — and it some cases, it actually could strangle bad projects. That's because state highway agencies still have to submit their infrastructure plans to their respective FHWA state division offices for review, and those offices, in turn, are obligated to answer to Washington.

biden admin to states: hey here's some way to use infrastructure funds to do green things, you know, cause the planet is heating up and could end all life on earth

— Oliver Willis (@owillis) February 10, 2022

mitch mcconnell: STOP THIS MAN NOW! https://t.co/pzUxj5zfB1

"US DOT has to give [states] the money at the end of the day, but they can use the bureaucratic process to make it as difficult as possible," said Benito Pérez, policy director for Transportation for America. "[Pollack] can definitely use the power that she has within those division offices to exert pressure in the review process."

Pérez was careful to note that some division offices may well shrug off the new guidelines, and that McConnell and Capito are right that Pollack's advisories are not legally binding.

But the governors are also right not to underestimate the awesome power of government bureaucracy, which has already stalled some of the most significant highway projects on their wish lists since Secretary Pete Buttigieg took the helm at DOT. Less than a year ago, the Texas Division of the Federal Highway Administration forced the state to pause a long-sought highway expansion in Houston to give the state time to investigate a civil rights claim against the project, partially at the national agency's urging; a similar project in Portland, Ore. faced a similar fate.

Pérez points out that the Civil Rights Act isn't the only tool at DOT's disposal to stop bad projects, either. In particular, an obscure and rarely-enforced federal code could give the agency grounds to deny states formula dollars for future projects if transportation leaders fail to repair broken infrastructure built with federal money — despite Congress' refusal to re-commit to a "fix-it-first" provision in the new infrastructure law itself.

"The FHWA could enforce that and say, 'well, we’re not going to give you money until you get this done,'" he added. "Other lines of code contradict [that one], but it's not impossible."

“We want to see states focus on repairing what they have before they build new things, and as they build new things have a plan to maintain it."@LeaderMcConnell said, nah, ignore that.https://t.co/xDkdSzFnH3

— Beth Osborne (@BethOsborneT4A) February 11, 2022

Pérez also cautions advocates not to underestimate the power of other state and regional leaders to subvert highway offices' road expansion plans. State senators, he points out, often have significant authority over the policies that dictate how federal dollars are spent, even in communities with transit-hostile governors. Just weeks ago, for instance, the Maryland state legislature overrode a gubernatorial veto that would have denied a funding increase to the state transit authority on grounds that it would deny the state DOT "flexibility" over their own budget, a common euphemism for giving them license to build more unnecessary highways.

Municipal planning organizations also wield more power over how federal funds are distributed regionally than many advocates realize — and by pressuring every transportation decision maker, Pérez says, advocates can really move the needle.

"There’s still an ingrained status quo for road capacity expansion, but there’s a slow movement to change that paradigm," he added. "And DOT is sending a signal that the status quo isn’t going to cut it anymore."