A slate of new guidelines will encourage all states to spend their federal safety dollars on protecting vulnerable road users, while requiring some to do it based on a new rule buried in the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law— but some advocates say both the recommendations and the rule could be even stronger.

On Wednesday, the Federal Highway Administration released updated guidance for how states should spend the money they get from the the Highway Safety Improvement Program — a program which, contrary to the confusing name, can be used on any road, not just highways owned by state DOTs — which will provide $15.6 billion over the next five years for projects aimed at curbing roadway deaths and serious injuries.

The document places a strong emphasis on the department's new national goal of ending road deaths completely, rather than merely making marginal safety improvements focused on drivers — a significant shift for a program that, until recently, allowed states to benefit from the federal money even if they set fatality reduction "targets" that wouldn't actually reduce deaths at all. Namely, the guidelines:

- explicitly note that projects aimed at protecting vulnerable road users "warrant additional consideration," over and above other types of projects.

- discourage states from utilizing the loophole in federal law that allows them to shift Highway Safety Improvement Program dollars to other federal programs not concerned with safety — something 23 states did last year — and encourages them to shift non-safety dollars into the HSIP instead.

- remind states that do "flex" their funds that there's a new policy folded into the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law which allows them to use Highway Safety Improvement Program dollars to cover the 10-percent state match required to access another pot of money called Transportation Alternatives — or, in other words, that they can get the federal government to cover the entire cost of bike- and walk-focused projects, rather than just 90 percent.

In 2021, 21% of the people who died using the Texas transportation system were pedestrians or riding bicycles at the time.

— Jay Blazek Crossley (@JayCrossley) February 2, 2022

Texas will be required to spend at least 15% of HSIP on pedestrian, bicycle safety improvements.

In FY22, @TxDOT spent 9.6% of the HSIP on ped/bike safety. https://t.co/njqYMXXN2p

The grants will be distributed to states based on a federal formula, which means that the Federal Highway Administration can't actually deny states money if they don't put people outside cars first — except in a few special cases.

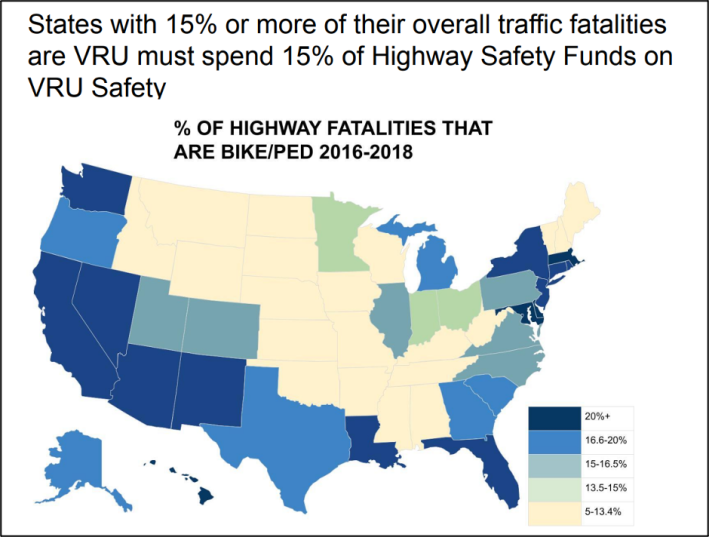

Under the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law, states in which vulnerable road user deaths make up 15 percent or more of total fatalities will now be subject to the new Vulnerable Road User Special Rule, which requires them to spend at least 15 percent of Highway Safety Improvement Program funds on projects specifically focused on those groups, or else give that money back to the feds.

The new policy is widely expected to unleash millions of new federal dollars on communities that previously devoted all their Highway Safety Improvement Program money to driver safety alone; in 2010, for instance, just six states put any of those funds towards bicycle- and pedestrian-focused projects.

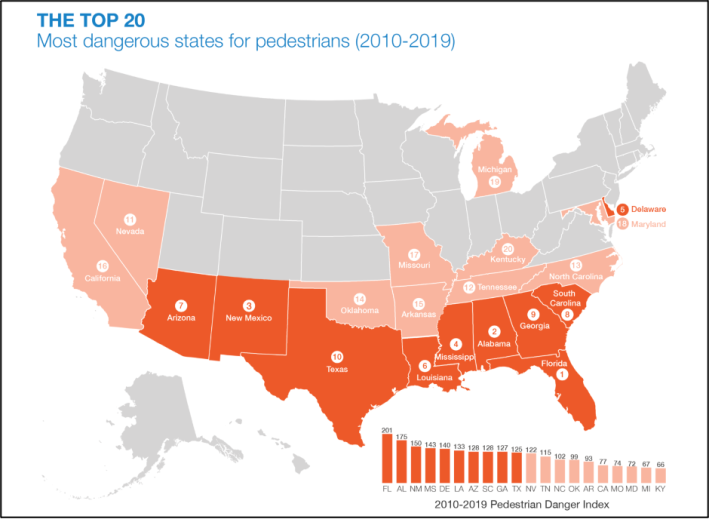

Some advocates have questioned, though, whether the scope of the new rule is too narrow — and whether all states shouldn't be required to spend more on vulnerable road user safety, regardless of that single metric.

Alabama, for instance — which is routinely ranked as the second-most dangerous state in the country for pedestrians, relative to how much they actually walk — would not be subject to the new law because just 12 percent of its fatalities are vulnerable road users, presumably because people are so likely to die when they travel outside a car that they don't even dare to try. Unsurprisingly, Alabama spent zero Highway Safety Improvement Program dollars on projects that made vulnerable road user safety their emphasis in 2020, give or take the construction of a single "pedestrian-friendly" shoulder on a highway that didn't list walkers as the project focus. Despite the recommendations in the new FHWA guidelines, Alabama state leaders won't actually be obligated to spend any more to protect vulnerable road users next year.

Rhode Island, by contrast, which has the lowest pedestrian fatality rate per 100,000 residents in the country, would be obligated to spend more on walking safety ... but the Ocean State already devoted 36 percent of its Highway Safety Improvement Program funds to vulnerable road users last year, and was widely expected to do the same in years to come anyway. But that still doesn't mean Little Rhody is doing a perfect job: 78 non-motorized travelers still died on its roads that year, signaling that transportation leaders should probably be spending even more to protect them.

The new guidelines have other potential shortcomings, too.

USDOT pointed out that up to 10 percent of Highway Safety Improvement Program funds can be spent on public awareness campaigns and "student sessions on bicycle and pedestrian safety," which some fear could be used to produce more of the same victim-blaming pedestrian safety campaigns that state DOTs churn out every year (particularly around Halloween), rather spending every available dollar on infrastructure to actually protect children and caregivers.

The Bipartisan Infrastructure Law also includes a new provision which allows states, for the first time, to spend Highway Safety Improvement Program dollars on automated enforcement, which could be a positive step towards ending police brutality and murder of BIPOC in the traffic realm ... or a way for cities to generate big revenue on speed-inducing roads that should be calmed before a camera goes up, depending on how they're implemented.

Still, if states take the DOT's Vision Zero goal seriously — and if the FHWA uses every available power of its office to pressure them to do so — the new-and-slightly-reformed Highway Safety Improvement Program could represent a turning point on U.S. roads, at least in the states that are required to spend the money right.