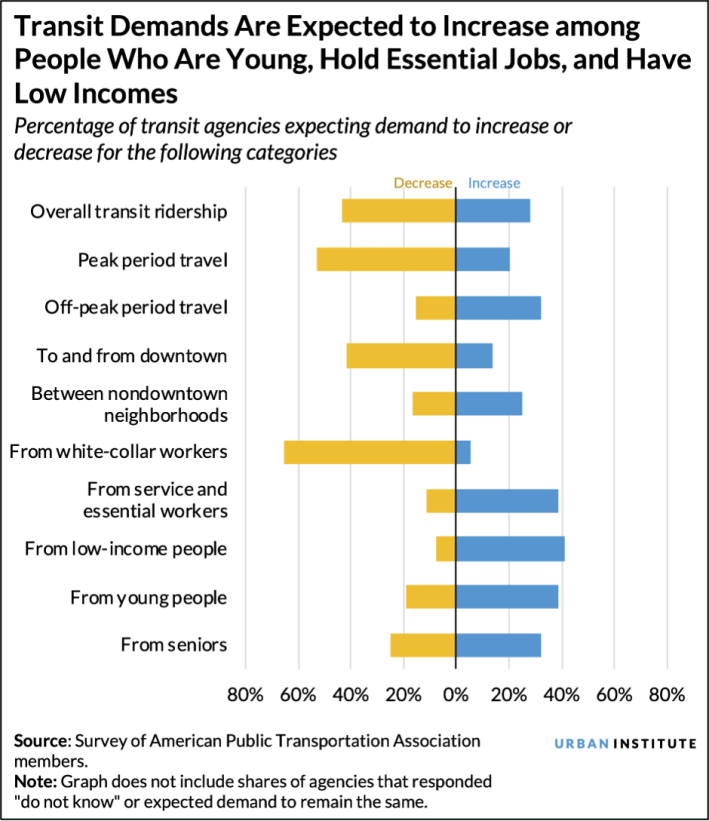

A staggering 88 percent of U.S. transit agencies expect that historically disenfranchised riders will be their primary customers as they recover from the pandemic — and many are planning to shift their service to center those groups' unique needs, a new study finds.

In a survey of 73 public transportation providers in the United States (and one in Canada), researchers at the Urban Institute found that nearly half of the systems intend to increase neighborhood-to-neighborhood service as they recover from Covid-19, and a further 34 percent plan to increase service during off-peak periods. That would be a drastically different approach than many agencies took before the pandemic, which favored the convenience of White collar commuters traveling at rush hour over essential workers and car-free travelers who are more likely to board the bus or train throughout the day.

Follow-up interviews with five of the agencies confirmed that a renewed commitment to mobility justice was helping to drive the shift.

"I get the impression that transit agencies have a newfound sense of purpose in ensuring that they’re providing for the mobility of people who have been historically disenfranchised," said Yonah Freemark, senior research associate at the Institute and a co-author of the study. "That’s encouraging them to approach transit investment and service in a way that they weren’t thinking about pre-pandemic."

That change of heart may not have been possible without federal support. Freemark points out that operational support from Washington has played a pivotal role in keeping transit routes running for the populations that need them most, even as ridership declined: an impressive 35 percent of agencies reported that they had returned to full service by August of 2021, and 50 percent plan to do so by 2022, with about third hoping to complete their recovery by the end of this year. Only 23 percent of respondents said they're not planning to restore service to previous levels, or are unsure that they'll be able to do so.

"Frankly, without that federal windfall, we’d probably be suffering much worst declines nationwide," he added. "We saw what happened after the Great Recession; agencies nationwide just slashed service, destroying the mobility of BIPOC across the country. That could have easily happened again. But federal action really worked."

Freemark is careful to note that a just pandemic recovery isn't a sure thing, despite agencies' best intentions. In some communities, crushing operator shortages have made service restorations challenging despite robust federal relief, and further operating funds to keep paying transit workers the wages and benefits they deserve in the long run aren't guaranteed. Critically, the Urban Institute survey also didn't ask how transit agencies have committed to adjusting their service as the pandemic drags on, but how they plan to adjust their service — which means equity advocates will need to keep them accountable for putting their money where their mouths are.

Still, Freemark is cautiously hopeful that with the right combination of support and advocate oversight, transit agencies can truly build back better, with the needs of the most transit-dependent at the center of everything they do — and in time, grow back their overall ridership, too.

"The transit agencies themselves are optimistic about being able to provide better service to undeserved communities, even though ridership has declined," he said. "What we need now is a long-term commitment from politicians to make it possible for agencies to execute on those plans, and to be able to achieve those successes."