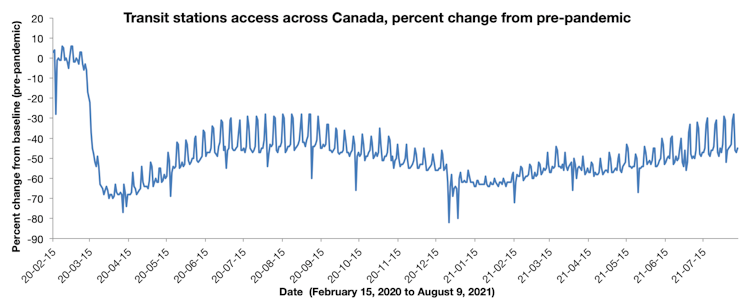

Public transit use dropped sharply when the pandemic hit as many people stayed home. And over a year and a half later, as fall approaches, vaccination rates increase and “normalcy” feels within reach, it is important to think about how commuting has changed and how we will need to adapt the way we plan for transit.

As people moved to cars and non-motorized transport over fear of infection through what some have called “forced togetherness,” transit agencies are worried it may take years to regain lost users — up to 10 years in Montréal’s case.

This is because people changed their habits, and changing habits takes time: research suggests it can range from 60 to 250 days. The pandemic has been long enough for habits to have changed; avoiding public transit, using a car and working from home are likely to stick.

With fewer riders funding the system, agencies and governments will need to rethink public transit promotion, funding, operation and expansion.

As researchers who look at telecommuting and travel, travel disparities and the economics of transit project funding, the past year has challenged much of our understanding of the way these issues will interact in the future.

Getting essential workers where they need to be

Throughout the pandemic, public transit played an important role in getting essential workers where they needed to be. By the end of 2020, 34 per cent of Americans were using public transit just as much as they did pre-pandemic.

Those still using transit were likely “transit dependent” riders, or individuals with no other available alternatives to access the workplace — like grocery store clerks with jobs deemed essential.

Transit operators had to adapt to maintain services. In England, some operators actually increased service to prevent packed trains and enable social distancing, leading to additional expenses while receiving less revenue. Other operators, like in Winnipeg and Toronto, had to reduce service given reduced revenues.

In March 2020, Montréal operators asked users traveling for COVID-19 tests to not use public transit.

A new world with increased remote work

One objective of public transit has always been to get people to work. For those who can’t work from home, the situation remains the same, but for the hundreds of thousands who can, getting the economics of transit fares right will be crucial.

A recent virtual conference of Québec transit operators raised the question over reconciling public transit with working from home.

Monthly transit passes having been the tool to entice users to stick with transit for decades. But the “new” weekly commute — now expected by Statistics Canada and some recruitment firms to range between two and five days — may make a monthly transit pass hardly seem worth it. Just how much remote work will stick remains to be seen, but Statistics Canada suggests 41 per cent would prefer spending half of their work week at home.

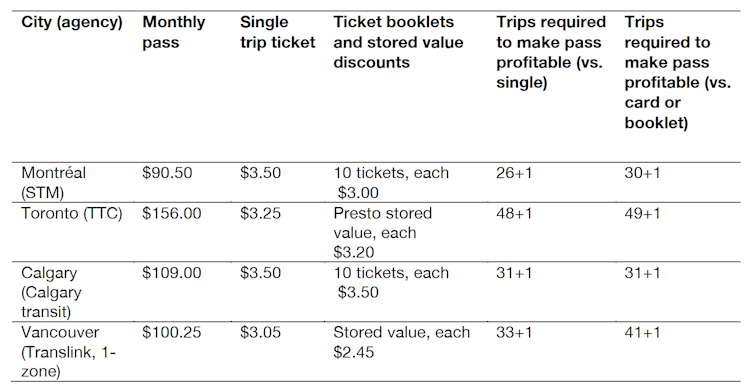

One way to weigh this decision would be to assess at what point a pass is more economical than single fares. By dividing the cost of a monthly transit pass by the single fare or bundled rebate, we can assess how many trips are needed before riders actually save money.

Depending on the city, it is currently profitable to own a pass for as little as 15 workdays in Montréal (one round trip per day), or as many as 26 in Toronto.

According to Statistics Canada’s estimates, transit agencies may need to cater to constant commuters, as well as commuters with 12 in-office days a month (three per week) and eight in-office days a month (two per week). By this account, only workers with abundant use of transit for other activities will be enticed to continue purchasing transit passes.

What to do, or at least to consider

Riders will need to recalculate the value of purchasing monthly passes and many may drop their use. Transit agencies need to consider adjusting fares to cater to commuters and become imaginative as to what will work for a variety of work weeks.

In Britain, a flexible tap-in tap-out system and automatic capping of fares may offer better deals for frequent users. An increasing discount as transit passes are used more frequently could reward frequent users and enable lower off peak fares. In the United States, the Southeastern Pennsylvania Transportation Authority started selling three-day transit passes, while New Jersey Transit announced a pilot program which will include a rewards program sponsored by local businesses.

The challenges to transit in coming years will be multiple: regaining riders, adapting fares, competing with and complementing other modes. The impact of remote work on downtown parking prices is another unknown. If property owners reduce parking fees, this could make transit even less attractive.

Some transit agencies now describe themselves as mobility managers, focusing not on getting people to use transit but rather on how to avoid driving. The potential for additional government funding given growing climate change wariness, may motivate other agencies to follow suit.

Perhaps the only good coming out of this pandemic is to have made the essentialness of transit more visible.![]()

This article originally appeared on The Conversation and is republished with permission.