A handful of critical policy changes buried in President Biden's bipartisan infrastructure megabill may quietly revolutionize life for people who walk and roll through U.S. cities, some advocates argue — especially if it's amended to include other progressive items from the House's visionary INVEST Act, too.

As much of the sustainable transportation community struggled with news that the so-called Bipartisan Infrastructure Bill (BIB) would deliver substantially more money for drivers than transit riders, some active transportation advocates expressed tentative excitement about the details of the 2,700-page tome — many of which, they argue, are more aggressive on protecting vulnerable road users than originally expected.

That's because the baseline transportation reauthorization bill within the mega-bill — the Senate Environment and Public Works Committee's Surface Transportation Reauthorization Act of 2021 — shares a lot of DNA with the House's much-lauded attempt at the same legislation, the INVEST in America Act, at least when it comes to the sections having to do with vulnerable road users.

Of course, the actual dollars behind those policy shifts still pale in comparison to the windfall the bill would deliver to highway-builders. But they're still among the biggest federal investments into vulnerable road user safety ever made — and they're likely far better than what could be passed if Democrats lose their narrow majorities in the House and Senate.

“We know this isn’t a perfect bill, but we’re concerned if it doesn’t pass this year, we could get a much worse bill in the next Congress," said Caron Whitaker, deputy executive director for the League of American Bicyclists. "I just think there’s a lot of good sections in this bill that are getting discounted because the INVEST bill is more progressive overall. ...We really want to see it conferenced [with the House] so the best ideas from both pieces of legislation can be reflected in the final text."

Here are a few areas to watch as the negotiations continue.

70 percent* boost for alternative transport

One of the subtlest shifts in the bill is also the most seismic: a shift from a flat, $850-million/year funding model for the Transportation Alternatives program to a dedicated 10 percent of the Surface Transportation Block Grant Program. The new model maths out to an average of about $1.3 billion a year, or about 70 percent more than the critical initiative gets now — exactly as much as the House bill promised.

But ...

Unfortunately, that promising topline number could be undermined if Senate succeeds in passing an amendment that would essentially cannibalize about a fifth of those dollars to deliver much-deserved funding for the Recreational Trails program — the other big pot of money for biking and walking, which focuses more heavily on rural areas — rather than fully funding both programs.

But if that can be fixed, advocates are cautiously optimistic — especially considering that another section of the bill would require every state in America to adopt a Complete Streets standard. That move which could theoretically drum up demand for future infusions into the TA program, since many won't have the money they need actually meet those standards without federal help.

Real consequences if states fail vulnerable road users

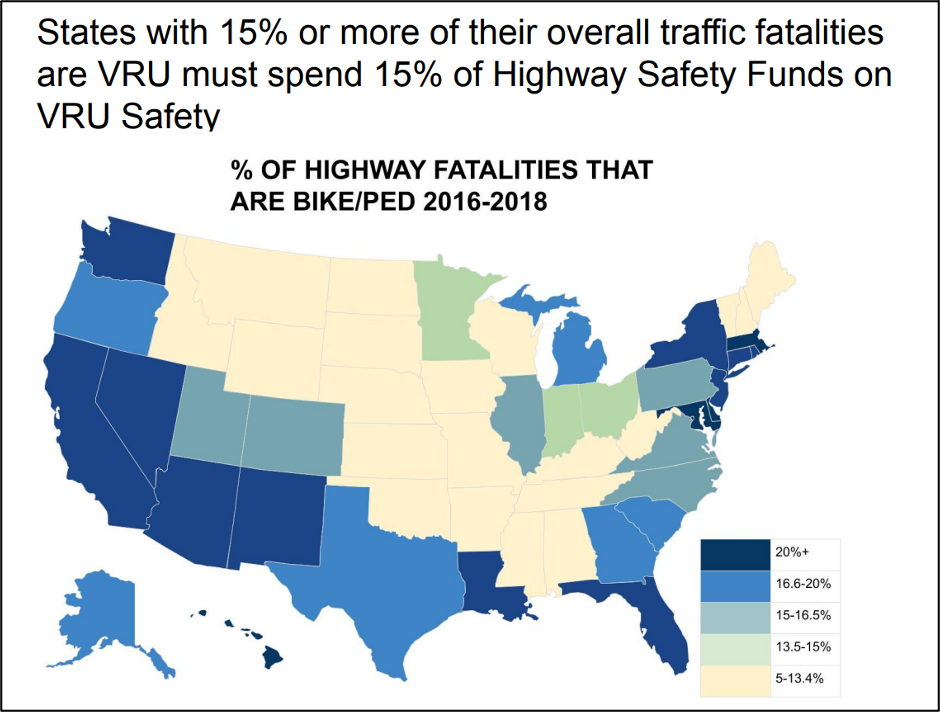

Under our current system, only about 1 to 2 percent of Highway Safety Improvement Program dollars are specifically aimed at saving vulnerable road users' lives — even when those road users represent a way bigger share of the total death toll.

Both the House and Senate bills would have fixed that, but many advocates think the Senate bill sets slightly stronger criteria for when a state would be required to take action. Under the bipartisan pact, if more than 15 percent of people who died on their roads were walking, biking, or using a micromobility mode and/or assistive device at the time, that state will need to devote 15 percent of Highway Safety Improvement Program dollars towards saving those lives until numbers go down — which could mean millions for protected infrastructure in those communities.

That approach is not without its tradeoffs, especially among less-urbanized states where people feel so unsafe walking or biking that they don't even bother trying, and thus don't have high percentages of VRU fatalities.

But it's an important first step, especially taken together with another section of the bill which would require states to identify where the most dangerous segments of their road networks are, something many of them famously don't know. They'd also have make that information public.

"That allows advocates to say, hey, you designated this street as dangerous, and you know how to fix it," said Whitaker. "We look forward to working with FHWA to help them do that well."

An overhaul on crash reporting and safety standards

One of the biggest surprises in the mega-bill was the inclusion of a slate of reforms proposed by traffic safety champion Sen. Brian Schatz (D-Hawaii) in a bill he formally introduced just one day before the infrastructure deal — many of which have been on advocates' wishlists for years.

The reforms include:

- An update to the New Car Assessment Program to include a consumer rating for how a vulnerable road user will fare if struck by that car — though it stops short of banning automakers from actually selling mega-cars that are unacceptably dangerous to walkers, bikers and others.

- A update to hood, bumper, and advanced driver assistance technology standards to reduce the number of injuries and deaths suffered by vulnerable road users who are struck by ultra-tall SUVs, pick-up trucks, and other dangerous vehicle designs that are driving the U.S. pedestrian death crisis — though those updates will be subject to a public comment period first.

- An overhaul on federal crash reporting standards to include more information about the circumstances surrounding the deaths of vulnerable road users, as well as to check police reports against hospital data to ensure that states are getting a full picture of their traffic violence crisis.

The bipartisan pact definitely doesn't check every box on car safety — and advocates in particular are frustrated that the bill neglected to require a lot of long-sought vehicle safety features, like automatic emergency braking systems. But it's a step in the right direction.

An overhaul on the MUTCD (sorta)

Reforming the deeply auto-centric Manual of Uniform Traffic Control Devices was a major focus of the safe streets advocacy community as the country headed into reauthorization.

The bipartisan bill would help make that happen, but the specific reforms it mandates are a bit of mixed bag. Many of the best changes — like explicitly prioritizing the protection of vulnerable road users above driver safety only, and requiring a fresh update to the document every four years to reflect the anticipated rapid development of autonomous vehicles — are counterbalanced with questionable ones, such as privileging edits suggested by the private council that wrote the regressive document in the first place, while throwing away over 25,000 citizen comments demanding better for the most vulnerable.

25,000+ comments urging the FHWA to reject recommendations from the National Committee on Uniform Traffic Control Devices that favored cars over people. And some Senator has slipped a provision into the infrastructure bill to adopt the flawed recommendations https://t.co/BPog7ES57p

— America Walks (@americawalks) August 2, 2021

"The big thing [the bill] is missing is requiring an end to the use of the 85th percentile speed limit setting method, which lets speeders set speed limits and does not consider people biking and walking," added Ken McLeod of the Leaugue of American Bicyclists. "Secretary [Pete] Buttigieg and the staff at FHWA can still address the 85th percentile in their rulemaking, and doing so is critical for their efforts to create a Safe System that reduces traffic deaths."

A lot more power for Pete

The outlook for active commuters is likely to evolve as the bill gets amended, but one thing is for sure: U.S. DOT Secretary Pete Buttigieg will play a big role in the nation's transportation future.

In a webinar held Monday by the Eno Center for Transportation, Transportation Weekly Editor Jeff Davis pointed out that a whopping $100 billion of the $1-trillion bill — including much of the funding for new safety programs aimed at protecting vulnerable road users — would be dispersed through discretionary grant programs under the purview of the Secretary, rather than through formulas, like the department has largely done for the last decades.

Davis called the shift "astonishing" and noted that it was "a big pivot towards the DOT being an even bigger grant making organization than [ever before]."

Notably, that astonishing shift includes a new $5-billion "Safe Streets for All" program, which would give local and regional agencies money to craft Vision Zero plans for the first time, as well as boosts to the RAISE program (formerly TIGER), the INFRA program, and a dedicated fund for megaprojects, all of which could be used to build better streets for VRUs — or to build more highway lane miles, depending on who holds the purse strings.

That's probably great news to those who have confidence in the multimodal ex-mayor's expressed commitment to building vulnerable road user safety and racial equity through the power of his office — but it might not be great news if Biden loses the White House in four years.