A new bill would give U.S. communities money to analyze how easy — or difficult — it is for residents to access the destinations they need most, and how their mode of transportation, race, income, age, disability, and other factors that affect their basic mobility.

The bipartisan bill, sponsored by Sens. Tammy Baldwin (D-WI) and Joni Ernst (R-IA) and named the Connecting Opportunities through Mobility Metrics and Unlocking Transportation Efficiencies (COMMUTE) Act, advocates for the establishment of a pilot program that would “provide data to states and local governments to measure accessibility to local businesses and important destinations, and inform investments in transportation systems.”

That might sound like something communities should already be doing, but they’re not. Developers and departments of transportation often are legally required to conduct traffic-impact analyses that estimate “level of service” for drivers before they build roads, buildings, and other developments, but those studies almost never estimate the effects on people without cars — and they almost never disaggregate their data to understand which groups will benefit or suffer because of their leaders' choices.

In fact, cities and states are too often in the dark when it comes to understanding the mobility barriers facing residents. Few U.S. cities bother to analyze pedestrian and bike volumes on their roads or to study how those behaviors might change during, say, a global pandemic. Data on how people of color and other marginalized groups get around are only collected nationally every six years as part of the National Household Travel Survey, which asks about trips in broad terms, such as “to/from work,” for “shopping,” and “other personal/family errands."

The failure to do a more granular analysis has real-world consequences for U.S. families. According to the National Equity Atlas, Black workers have 12 percent longer commute times than their White counterparts across all modes — and statisticians don’t even know how long it takes the average BIPOC to reach essential services. Experts do know, for example, that Black Americans are 2.49 times more likely to live in a neighborhood without a full-service grocery store, and three times less likely to have access to a personal vehicle, but not how long it actually takes them to make a household food run on average — which might vary a lot if there’s a highway between home and the shopping center, instead of a direct-access bus route.

Advocates are hopeful that the bill could help communities answer such fundamental questions — and give cities a map of where they need to improve access.

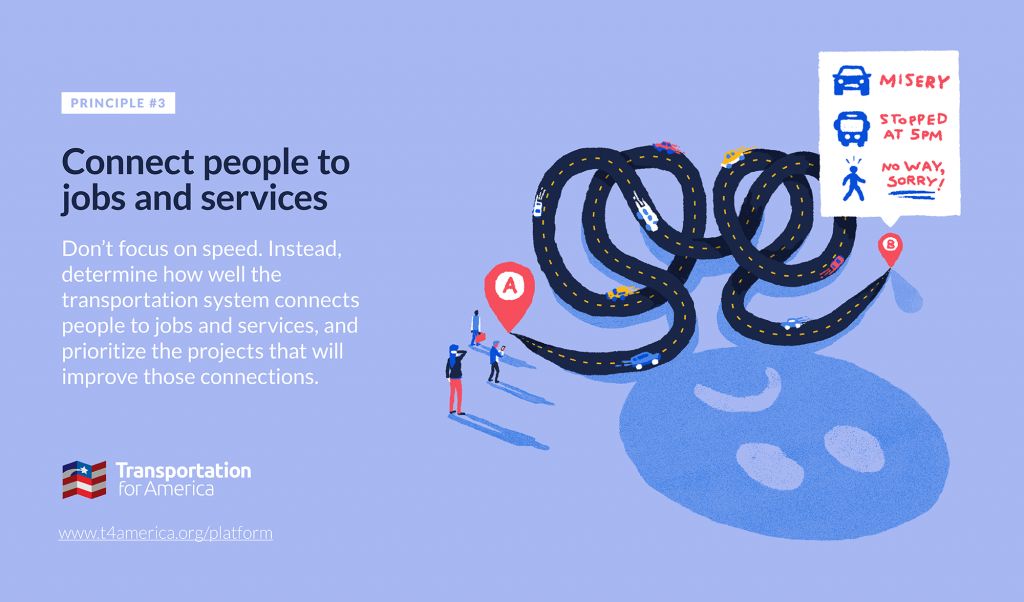

"The COMMUTE Act is about reorienting our federal transportation program around what counts: getting people where they need to go," said Beth Osborne, director of Transportation for America. "Sens. Baldwin and Ernst continue to be leaders in elevating the importance of measuring whether the transportation system connects people to jobs and essential services, not just how quickly vehicles move as we do today. I'm grateful to both senators for their continued bipartisan leadership on this issue."

The COMMUTE Act won’t give transportation leaders all the tools they need to improve access for the most marginalized — and it won’t hold those leaders accountable for what they do with the new data. The text of the bill doesn’t specify the size of the pilot program, the amount of money that will fund it, or how many communities can participate (although, notably, it does include small, rural cities and entire states as eligible participants.) It also doesn’t obligate leaders to prioritize transportation projects that make it easier for non-drivers and other under-served groups to get around, as do states such as Virginia.

Still, the bill could be an important step toward removing outdated metrics like “level of service” from our transportation vocabulary — and toward getting DOTs to measure and treasure statistics that truly reflect how all their constituents get around.