Stories about miniature emergency service vehicles are spreading like wildfire on Twitter — and re-igniting a movement to get city leaders to shrink their engines to a scale that makes sense for the jobs they most frequently do, rather than widening all their roads to fit monster (fire)trucks.

Late last week, advocates were introduced to Kiri, an adorable Japanese fire engine from the early 1990s that’s not much larger than a standard sedan, featuring its very own anthropomorphic Instagram account and a following made up largely of its San Francisco neighbors. That was followed shortly thereafter by the introduction of as-yet-un-nicknamed electric mini-truck in the District of Columbia that's roughly the size of a shuttle bus; even a tongue-in-cheek ode to the vintage Lego fire truck got in on the action … paired with today’s Lego-EMS vehicle, which has grown to pedestrian-killing proportions even as Legopeople have remained the same size.

Happy Thursday to Kiri, the tiny Japanese fire truck bringing joy to San Francisco 🚒 pic.twitter.com/qTbUpt6S0T

— San Francisco Chronicle (@sfchronicle) April 29, 2021

— DC Fire and EMS (@dcfireems) April 29, 2021

Lego City has become increasingly hostile to pedestrians.

— Cycling Professor 🚲 (@fietsprofessor) April 30, 2021

Compare the fire truck of the 1990s vs 2020s. Note the additional screen blocking the drivers' view. pic.twitter.com/dNx1kMlerd

Of course, the Legomobile isn’t actually fighting any fires — but neither are the other two, either.

Kiri did once shuttle around the volunteer firefighting squad in a tiny mountain town of Kirigamine, Japan, but today, it’s owned by a private citizen in the Bay Area who uses it mostly to bump Tony Bennett songs on the streets of his neighborhood. Local advocates in the nation’s capital, meanwhile haven’t yet been able to confirm whether DC Fire and EMS is actually buying the mini-truck they helped go mini-viral, or simply staging a photo-op about one potential future of the department's vehicle fleet. (Officials haven’t answered Streetsblog yet, either).

But there’s no doubt that American fire departments could effectively stop many blazes with small-format vehicles like these — and they could certainly do the rest of their jobs without a giant hook-and-ladder, or the overbuilt road network that cities keep building to accommodate such massive EMS vehicles.

In 2018, less than 3.6 percent of fire department calls in the U.S. actually involved stopping something from burning down, give or take the roughly 4 percent of calls logged under a broad category that includes five-alarm blazes requiring multiple stations. A whopping 64 percent involve a call for medical assistance unrelated to a fire, including many of the roughly 6.7 million car crashes that happen every year.

But even the most serious crashes don’t always require first responders to have easy access to high-capacity hose, nevermind a super-tall ladder designed for putting out a fire on a skyscraper.

Even the arsenal of medical equipment on board big trucks isn't always necessary. Roughly 7.8 percent of EMS calls involve people suffering a mental health crisis with no physical injuries at all; in one city in British Columbia, paramedics on bikes are able to successfully respond to drug overdoses, diabetic distress, and many other emergencies using nothing more than the equipment that they can carry on bikes, calling ambulances for back-up only when needed.

But for generations, the giant red engine has been the virtual default in U.S. communities — and its size has been used to justify keeping countless roads ultra-wide and ultra-dangerous, just to accommodate our preferred public safety vehicle.

In his book Walkable City Rules, city planner and urban designer Jeff Speck blamed the ever-growing fire truck on a combination of the unintended consequences of labor agreements and (definitely intended) corporate influence:

“Over the years, firefighters’ unions have introduced contractual language stipulating the minimum number of firefighters on a call,” Speck wrote. “Simultaneously, firefighting equipment suppliers have infiltrated the ranks of the organizations drafting official guidelines for firefighting equipment. The unsurprising outcome: ever larger fire trucks.”

Here's the kicker: even the biggest hook-and-ladder can navigate a safe, narrow city street better than most planners would assume.

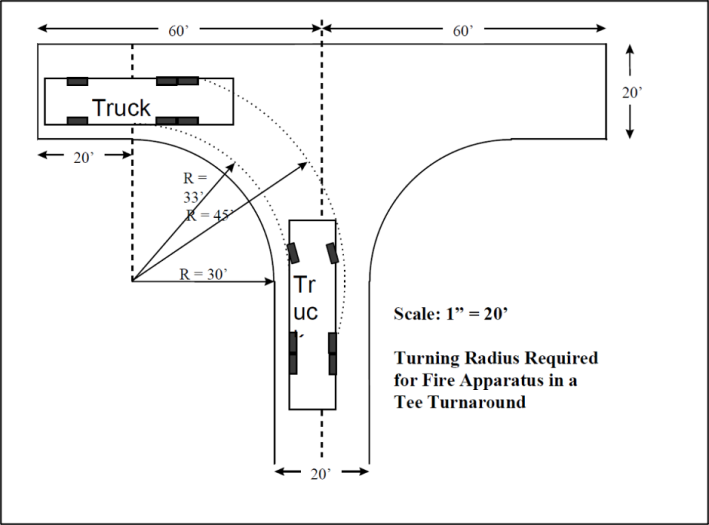

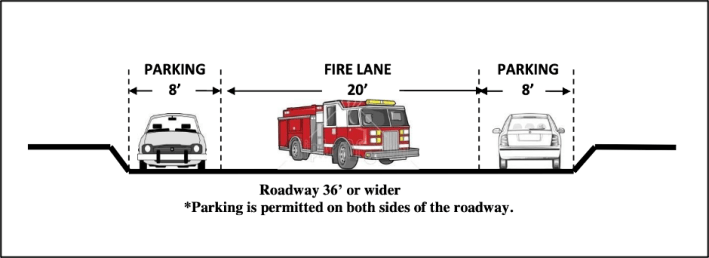

Cities that require huge minimum curb radii to accommodate a turning fire truck (and nix life-saving designs like curb bump-outs) ignore the fact that firefighters can just use their sirens to cross into the opposing lane in a pinch. The “20-foot clear” standard outlined in the Universal Fire Code, which recommends that cities maintain “20 feet of clear space between [fire trucks and] any obstructions such as parked cars,” is necessary for cul-de-sac-packed suburbia where there’s only one path to each structure that might be set ablaze, but less so when a street can be entered from both ends. And that egregious standard isn’t even a law — it’s just treated like one by city planners across America who unnecessarily prioritize ultra-convenient EMS access over basic pedestrian safety.

By shrinking more of America’s fire trucks to Kiri-scale — or even simply to the size of the far-more modest engines that other countries around the world rely on with no documented downside impact on fire risk — fire code doesn’t have to be the enemy of safer, narrower road designs. That'd be especially true if fire departments were more judicious about when they actually need to send a dozen firefighters and a massive vehicle to the scene of an emergency instead of sending a single paramedic on a bike — and if we contended with the size of all the other mega-trucks in our city fleets, too.

One thing's for sure: we'd make our emergency response systems a whole lot cuter in the process.