President Biden was hailed this week by some antiracist transportation advocates for calling out federal highway projects for destroying Black communities — and then lost points by failing to call for reparations to the people harmed by those federal projects.

In a memorandum about his administration's plans to reverse housing discrimination released on Tuesday, Biden touched on how government transportation and housing polices worked together to created "legacies of residential segregation and discrimination [that] remain ever-present in our society":

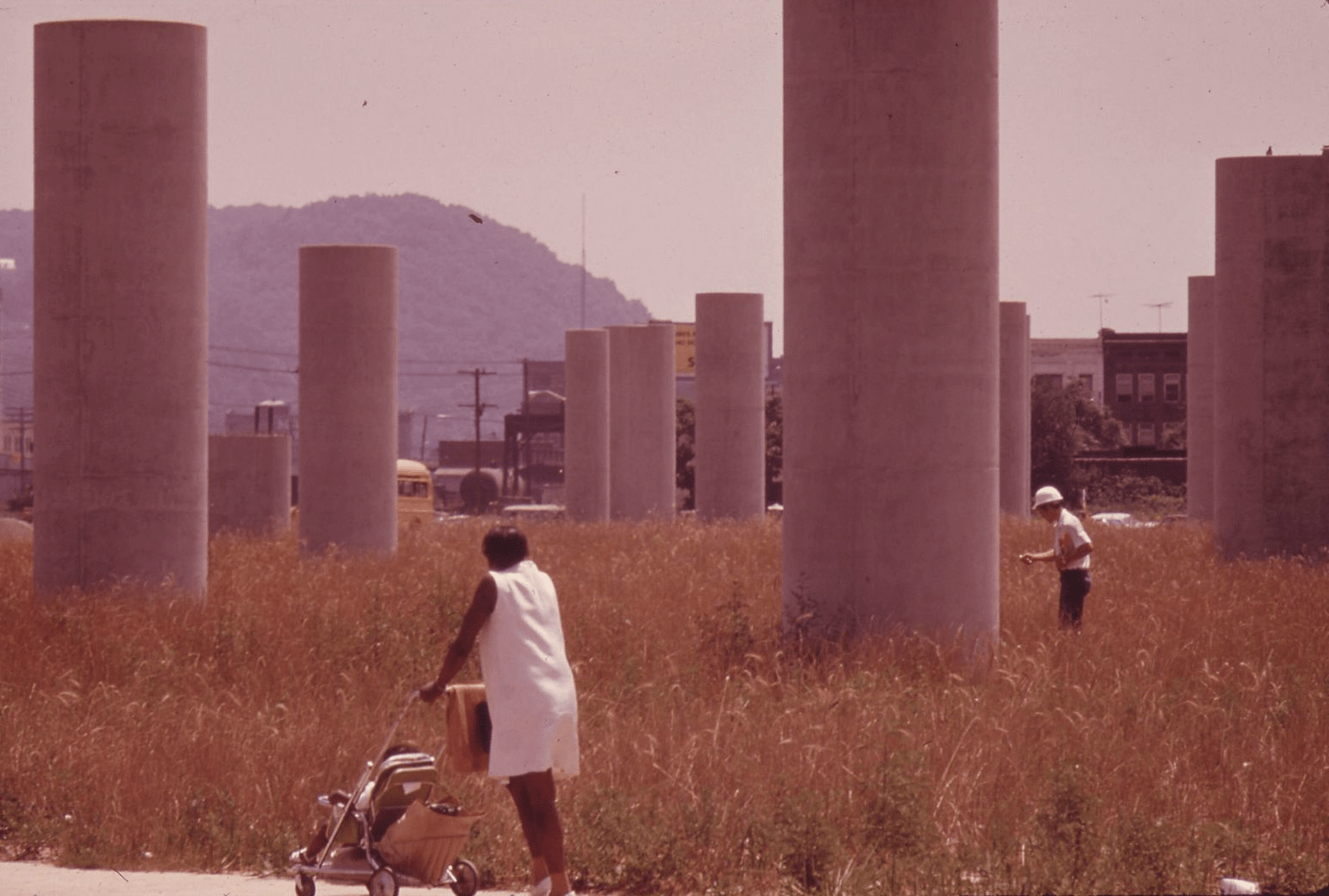

The creation of the Interstate Highway System, funded and constructed by the federal government and state governments in the 20th century, disproportionately burdened many historically Black and low-income neighborhoods in many American cities. Many urban interstate highways were deliberately built to pass through Black neighborhoods, often requiring the destruction of housing and other local institutions. To this day, many Black neighborhoods are disconnected from access to high-quality housing, jobs, public transit, and other resources.

The federal government must recognize and acknowledge its role in systematically declining to invest in communities of color and preventing residents of those communities from accessing the same services and resources as their white counterparts. The effects of these policy decisions continue to be felt today, as racial inequality still permeates land-use patterns in most U.S. cities and virtually all aspects of housing markets.

As part of the Federal Highway Act of 1956 to which Biden refers, the federal government put up 90 percent of the cost of interstate highway projects, heavily incentivizing states to use eminent domain to raze what they deemed "slum" neighborhoods to make way for the new asphalt, in a process cruelly termed "urban renewal."

In virtually every city that took advantage of the program, low-income communities of color were specifically targeted for "slum" clearance, displacing families and destroying one of their most important forms of intergenerational wealth. Residents who remained in the area adjacent to the new highway face increased rates of serious pollution-related health conditions and poverty to this day.

But despite those words about the federal government's record of racial injustice, the regulatory actions outlined in Biden's order focused exclusively on "examining the effects" of Trump-era housing regulation rollbacks, rather than on calling for meaningful action at the USDOT itself.

To some advocates, that felt like a glaring omission.

"The White House memo failed to even mention the department and program that allowed those highways to be built," said Beth Osborne, director of Transportation for America. "The Department of Transportation should provide guidance and tools that communities need to bridge or remove those highways and should work with the Department of Housing and Urban Development to identify ways to ensure these neighborhoods remain affordable for current residents once such an improvement is made."

Have to point out that, while this @WhiteHouse memo is a great start, it fails to mention the program or department that allowed and funded those highways to be built...@USDOT. As much as I love @HUDgov, it isn't their job to clean up @usdot's mess alone.

— Beth Osborne (@BethOsborneT4A) January 27, 2021

Transportation for America is among the advocacy groups that have called for bolder action from the federal government to begin the work of repairing the racist legacies of the urban renewal era. In December, the groups called on the next administration to establish a $5-billion fund that could help states remove their downtown highways and establish community land trusts for the benefit of neighboring residents.

Some advocates of the bill were hopeful that Biden's memorandum at least signaled that the administration understands the role that transportation reform must play in creating a more just society, even if the president didn't make that reform a focus of the recent order. (Biden’s nominee for Secretary of Transportation, Pete Buttigieg, has also acknowledged the racial injustices wrought by previous DOTs, including at his Senate confirmation hearing and on his Twitter.)

"It's encouraging to see the president, after only a week in office, acknowledge the racist legacy of the Interstate era and the damages these highways still cause to Black and Brown communities today," said Ben Crowther, program manager for Congress for the New Urbanism, which helped to write the bill. "Now, there's an opportunity to repair this damage by removing the highways that for too long have created barriers to quality housing for those who live around them."