Walking and cycling fatalities on U.S. roadways declined slightly in 2019 — but total crashes and injuries increased, which may indicate that doctors are getting better at saving lives after collisions while our streets remain as dangerous as ever, according to the final federal numbers for last year.

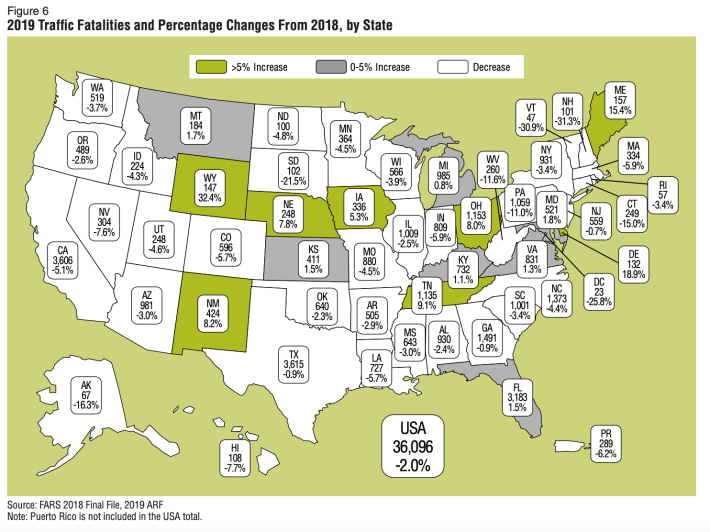

In its count for 2019 — as always, federal safety stats are released on a two-year delay — the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration reported that 36,096 people died preventable deaths in motor vehicle traffic crashes, or about 2 percent fewer than the year before. Those grim numbers include 6,205 pedestrians and 846 cyclists.

The agency hailed the statistics as evidence that our roads are getting safer, and downplayed the grimmest statistic: There were 6.76 million crashes in 2019, up from 6.74 million crashes the year prior. That's a small increase, but it is an increase nonetheless.

And despite a slight drop in deaths, the total number of people injured in traffic crashes actually rose by about 30,000 in 2019 compared to the prior year — which could indicate that our progress towards Vision Zero is being won in the emergency room rather than in the streets. Injuries in the "non-occupant" category — the umbrella term for pedestrians, pedalcyclists, and assistive device users traveling outside cars — increased by 2.2 percent — and they rose an especially troubling 4.3 percent among cyclists.

The 1.7 percent drop off in vulnerable road user fatalities is, of course, essentially a plateau. But it is the first time that pedestrian fatalities have declined by even a negligible amount since 2009 — and it's at least a little better than where we expected to be. As recently as six months ago, experts were projecting that 2019 fatalities would reach the highest levels seen since 1988; instead, the country came in slightly lower than our 1990 numbers. (Which isn't much of a win, since 1990 was a pretty bloody year for walkers, but in 2020, we'll take our silver linings where we can get them.)

On a state-by-state level, some of the numbers were even worse. Ohio, New Mexico and Tennessee all allowed eight percent or greater increases in total fatalities, while Wyoming and Maine posted horrifying double-digit increases.

Of course, it bears repeating that even this modest decrease in our death toll is nowhere near where we should be to end our national traffic violence epidemic, which other countries have already succeeded in doing.

And some of NHTSA's own stats may help explain why our progress has been so slow. The Administration also reported that since 2010 pedestrian fatalities in urban areas have increased a whopping 62 percent, in part because of a 15-percent increase in vehicle miles travelled over the same period. (Clearly, disappointing investments in sustainable infrastructure like transit have a little something to do with that.)

The SUV-ification of America also played a likely role. NHTSA analysts found that deaths among the occupants of vehicles classed as "large trucks" increased 13 percent in a single year — probably because there are more and more of them on our roads — while the number of non-occupants were killed by megacars increased by 2.9 percent. Meanwhile, the number of injuries involving the largest vehicles on our roads skyrocketed 33 percent, far outpacing even SUV and pick-up truck adoption.

Before we celebrate this nominal win our traffic violence crisis, street safety advocates would be wise to wait and find out whether we've simply replaced a handful of roadway deaths with a boatload of life-altering roadway injuries. But because NHTSA doesn't require state and local agencies to report on countless key factors, including the severity of traffic crashes, we probably won't get that answer anytime soon.