As coronavirus cases surge nationally, many scientific studies are reassuring essential workers that it's largely safe to take public transportation (if they use basic precautions) — and reminding Washington that it's past time to give transit agencies the relief they need.

Despite an early panic that sent ridership plummeting and kept it low, public transportation has proved to be one of the most COVID-safe places to be outside the home. Scientists think that's because many public transit vehicles are relatively uncrowded, well-ventilated, and usually not the site of the kind of boisterous conversations that can accelerate the spread of airborne particles — not to mention the fact that most transit agencies are requiring (and sometimes even supplying) personal protective equipment to passengers.

COVID might functionally destroy public transportation in New York and across America. Not because the buses or subways are unsafe, but because we still have a Republican majority in Congress https://t.co/uUw9OCHVBN

— amb ☀️ (@ambrown) November 18, 2020

In fact, scientists think that most intra-urban public transit trips are too short for passengers to inhale the high concentration of aerosols necessary for virus transmission, and some epidemiologists think that shared car services, such as Uber, may be more dangerous than mass modes.

Here are some of the many studies that suggest that transit is safer than anyone guessed at the start of the pandemic — and that the next Congress should make saving mass transportation its first priority.

No COVID clusters on trains in Japan

Japan is known for packing people into its subways like sardines — but not for giving those commuters COVID-19.

Researchers at Kyoto University made headlines months ago for their preliminary study of more than 3,000 early coronavirus cases, which found that, from January through April, no super-spreader events took place on public transportation — none. The conclusions held after the study passed peer review; it was published in the Journal of Emerging Infectious Diseases in September.

It bears repeating that Japan's success in keeping the virus off the Metro likely has to do with the fact that commuters began wearing masks on public transportation long before the coronavirus, thanks to the tough lessons of the SARS epidemic. That's just the latest reason not to leave your CDC-approved, three-ply mask at home.

Paris Metro passengers stayed coronavirus-free

Paris also has found no evidence that public transit contributed to any of its large COVID-19 clusters — and robust public support for the mode is probably why.

Of more than 150 super-spreader events in the French capital from May through June (defined as an occasion during which five or more people became infected after spending time in the same area) researchers found that none could be traced back to Paris's public transportation system.

That's likely because Paris Mayor Anne Hidalgo acted quickly to issue a mask mandate and outfit the transit agency with the World Health Organization-recommended tools it needed to keep passengers and workers safe. American leaders haven't had the federal support they need to be as proactive; perhaps that will change with the new administration.

Milan eases transit restrictions, doesn't see a case spike

Italy locked down some transit networks when it became a COVID-19 hotspot early in the pandemic. But as the weather warmed and cases subsided, commuters in Milan flocked back to trains — and positive cases didn't spike.

In late May 2020, the Milanese government took the extraordinary step of allowing trains and buses to operate at 80 percent capacity with mandatory customer masking, a threshold that some experts thought was far too high for appropriate social distancing. But Milan's COVID-19 case load stayed remarkably flat all summer — until September, when the weather became colder and Milanese residents began to pack restaurants, bars, and other enclosed public spaces.

Now, some Italian experts are, in fact, blaming public transportation for the city's second wave — but most think that a lack of enforcement on the 80 percent limit caused the problem, rather than the fact that the subway is running. Prime Minister Giuseppe Conte recently issued strong restrictions on pretty much everything but public transportation; if it's enough to stop the spread, it might indicate where COVID-19 is — and isn't — running wild.

Meanwhile, U.S. transit vehicles are nowhere near their capacity limits.

Americans aren't catching COVID on the bus — but they are being killed by drivers

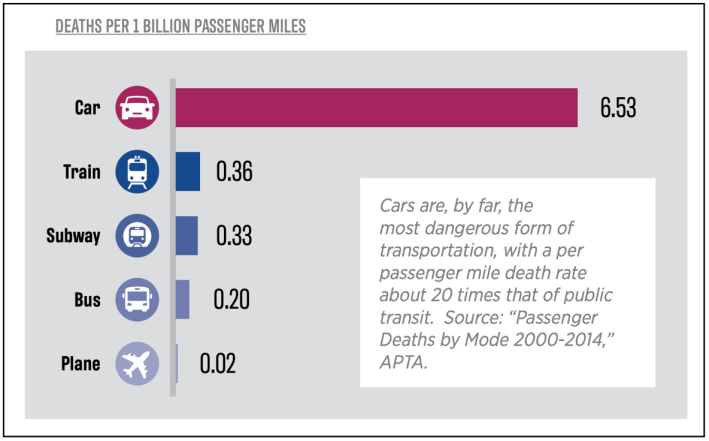

Perhaps the best argument for sticking to transit is that your chances of dying behind the wheel are likely way higher than your chances of contracting a fatal case of COVID-19 on a subway.

As the American Public Transportation Association pointed out in a recent report, "passengers are about 20 times more likely to experience a fatal crash in a car than when using public transit," because of the dangers of the high-speed auto travel of typical American commuting. That's before we even talk about drivers' high rates of sedentary-lifestyle diseases and the long-term health effects of pollution and climate change.

And of course, it bears repeating that while contact tracing here hasn't been nearly as robust as in the countries above but, like in Italy and France, no COVID-19 infection clusters in the U.S. have been attributed to encounters on public transportation.