A single, 38-year-old transportation law has locked America into a car-dominated status quo for far too long — and advocates believe the next Congress should finally fix the problem.

Transportation for America is mounting an effort to end the "80-20 split," a Reagan-era policy that restricts the Department of Transportation from spending more than 20 percent of Highway Trust Fund revenues on transit projects. The little-known rule has long been decried by advocates as the single largest structural barrier to greening our transportation sector at large scale, and repealing it — as well as the policy that allows states to "flex" (read: steal) as much as $48 billion a year that are supposed to be dedicated to transit projects to cover shortfalls in highway revenues — would be a game-changer.

Striking down the 80-20 split, though, will require a little lawmaker education. When it was first written in 1982, the famous ratio was actually marketed to pro-transit congresspeople as a boon to their cause — because before it, public transportation got no money at all from the nation's rock-bottom fuel taxes. U.S. Department of Transportation Secretary Drew Lewis initially proposed the ratio in order to convince big-city congresspeople to support increasing the gas tax in the middle of a recession, arguing that devoting 20 percent of a new five-cent increase to a new Mass Transit account within the Highway Trust Fund would give urban areas a bigger share of the new construction jobs the tax would produce.

But what was once an important step forward for sustainable travel soon transformed into a regressive trap. Rather than just the first effort on the path to more equitable transit funding, the 80-20 split soon became regarded as a foundational edict, essentially locking the Department of Transportation into an ironclad ratio that prioritized roads over trains tracks and highways over bus lanes. And it's stayed that way for decades, even after the American public learned what global warming was in the late 1980s — a development that should have demanded that America start shifting its funding towards less polluting modes.

T4A thinks giving the federal government more flexibility on how they spend those gas taxes is essential to repairing the harm done by the Reagan-era policy — and they're recommending that the next Congress devote at least 50 percent of funding to mass modes. But the group also questions whether, in the future, we could go even further.

"Why shouldn’t transit receive 80 percent or even 100 percent of transportation dollars?" wrote Emily Mangan on the organization's blog. "We are not saying that other modes should not receive any money. The point is that all assumptions should be questioned and funding should go to projects that create jobs quickly in a stimulus bill and support today’s needs and goals, not those of 40 years ago."

Here are three strong arguments in favor of letting federal dollars flex in transit's favor (and a petition you can sign if you agree).

The Highway Trust Fund doesn't pay for our highways anyway

The biggest political obstacle to giving transit a bigger piece of the gas tax pie has always been the perception that drivers pay their taxes at the pump with the expectation that their money will be spent on building and maintaining roads for drivers — and if the fund runs a surplus, well, that cash should just go towards building better roads, not subsidizing transit.

The trouble is, the Highway Trust Fund has never run a surplus — and all those gas taxes actually don't cover the costs of our wildly expensive road network. The federal gas tax has not changed since 1993, even as we've built more and more highways across the nation: in 2016, for instance, the fund was authorized to pay out $43.1 billion in highway contracts over the course of the year, but actually raised just $36.2 billion at the pump. And those are just the most recent numbers available that quantify how drastically the gas tax under-performs; the Fund on the whole has been in debt since 2008, requiring the government to siphon about $144 billion from general funds in the years since — plus all those "flex" dollars stolen from transit agencies.

Maintaining the 80-20 split, advocates argue, is just a bandage over what we really need: a slate of new, adaptable road funding mechanisms that reflect the actual damage that drivers do to our roads, and can actually cover the needs of our highway system as they change over time. A combination of vehicle miles travelled taxes, variable congestion tolls, and emissions fees on larger vehicles could be a place to start — but we shouldn't wait on finding that magic recipe to #EndTheEightyTwentySplit.

Funding transit could help end our highway maintenance backlog

Of course, the idea of pulling any funding for the highway system in the midst of a terrifying road maintenance crisis sounds a little irrational — at least at first. And some advocates argue that if we just ease up on "flexing" all those transit dollars away from public transportation, the 80-20 split could put a few more drivers on the bus, lessening the pressure on our roads just enough to give state DOTs the money and space they need to fix all those crumbling roads and bridges once and for all.

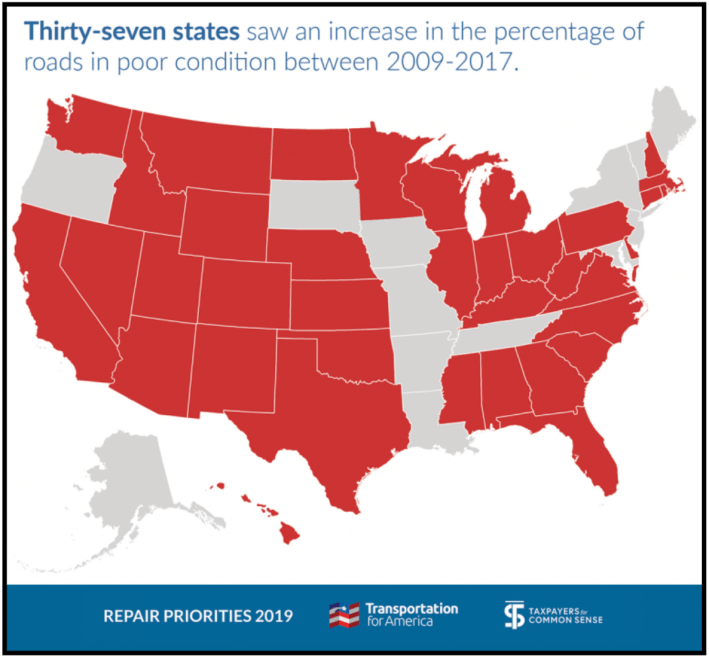

But most Americans don't realize that many states spend their highway trust fund dollars on building more roads rather than maintaining the ones they have. Mississippi, for instance, spent a whopping 77 percent of its capital funding last year on roadway expansion, even though the percentage of its roads that were rated in "poor" or "dangerous" condition by engineering groups like the American Society of Civil Engineers actually increased over the same year. Ditto Arizona (52 percent), Nevada (54 percent), North Carolina (55 percent), and more — a phenomenon that's predictable, considering how much our culture applauds politicians for christening new highway interchanges, and how relatively few plaudits they get for repairing potholes. (By comparison, Massachusetts spends just 4 percent of its capital dollars on new roads.)

Meanwhile, a Goldilocks approach to sustainable transportation funding won't save the planet — and one penny of a five percent tax isn't nearly enough to build the kind of strong transit network we'd need to make car-free commuting a viable option for American travelers, nevermind a truly attractive one. Paradoxically, giving highway agencies even less money — and diverting that cash to alternative modes now — could be the shot in the arm our construction-addicted states might need to finally buckle down and do relatively inexpensive maintenance projects, rather than continuing to justify expensive new road-builds that only grow the percentage of trips we collectively take by car.

We've already ended the 80-20 split — now we just need to make it permanent

Tradition is a pretty poor argument for maintaining bad policy. But when it comes to the 80-20 split, some norms have already begun to fall away on their own in the last few months alone — and now it's just a matter of making the change permanent, rather than a pandemic-era fluke.

"Whether legislators realized it or not, the recently passed $2-trillion CARES Act has already disrupted the status quo to deal with immediate needs," wrote Emily Mangan of Transportation for America. "The act includes $25 billion in direct, emergency assistance for transit at a time when revenue is plummeting. That’s more than double what the federal government usually spends on transit in a year."

That $25 billion wasn't enough to prevent agencies from cutting service and borrowing cash to stay afloat, but it was a seismic shift in what most Americans thought was possible – especially considering that highway agencies got virtually no relief, drivers didn't exactly find themselves stranded.

Once the pandemic ends and revenues rise, Congress will have the option to do something truly radical: funding transit agencies adequately for the first time in U.S. history. A 50-50 split is a start — and in time, we can do even more.