Time for a pop quiz! (Don't worry, it's open book: feel free to hop on Google.) What are the 10 most dangerous intersections or corridors for pedestrians in your city, and what percentage of total crashes occur in these areas?

If you don't know the answer, and can't easily can't find it using the search function on your city's website, you're not alone. According to an analysis from Streetsblog, seven of the 20 largest cities in the U.S. do not have an easily accessible High Injury Network map, which details the regions of a road system where pedestrians and cyclists are most often severely injured or killed.

And often, those concentrations are staggering. In Minneapolis, just 9 percent of streets are the site of 70 percent of the worst crashes; in Cleveland, a third of all road fatalities occur on just 7 percent of roadways; in Austin, a shocking 70 percent of deaths and serious injuries happen on just 7 percent of streets; and the list goes on.

But in other cities — including behemoths such as Chicago, Houston, and Phoenix — High Injury Network maps can't be found on city websites. In New York, for example, such frequent crash zones are called pedestrian "priority" areas — and they're buried inside annual pedestrian master plans that vaguely promise change but don't always translate into meaningful action or fatality reductions.

And without transparent and accurate information, transportation professionals may overlook the lowest-hanging fruit in the fight to end traffic violence — and advocates may struggle to hold leaders accountable.

Where crashes happen

High Injury Network mapping is relatively new. The first one was born in San Francisco in just 2015, one year after the city adopted its Vision Zero plan to end roadway fatalities by 2024 and set about finding the most urgent battlefronts in the war to build a safe road network.

"We knew we wanted to have our initiative be very data-driven," said Tom Maguire, director of sustainable streets for the San Francisco Municipal Transportation Agency. "We also knew that reengineering our streets was going to be a huge part of any success we had, so we knew we had to prioritize."

The agency worked closely with the Department of Health to cross-reference crash reports from the previous five years with hospital data that offered more thorough documentation on crash severity than police reports alone. Maguire admits that this kind of close collaboration between two government agencies can be unusual — the fact that San Francisco has just one trauma center didn't hurt — but it was indispensable to understanding the full scope of the problem.

"Over a third of the crashes we found actually didn't appear in any police report — they were only in the hospital data," said Maguire. "Some people just prefer not to interact with police. ... There’s a whole skill set that epidemiologists have that traffic engineers can learn from."

What Maguire and his colleagues found surprised them: a whopping 70 percent of severe injuries and deaths on their roadways occurred on just 12 percent of city streets. And the majority of those crashes happened in historically disinvested areas, rather than the moneyed corridors that were more often being targeted for street improvements as part of economic development projects.

"There’s a huge overlap between the map of neighborhoods that are more dangerous in terms of traffic violence and the maps of neighborhoods that are disproportionately elderly, low income, low English proficiency, and non-white," said Maguire.

Mapping — and solving — an unequal epidemic

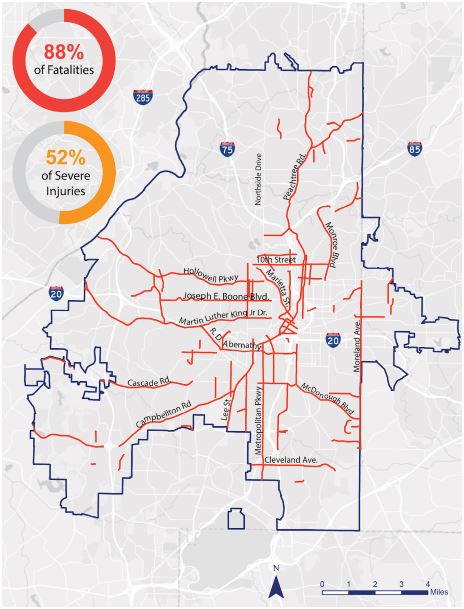

San Francisco isn't the only city that's found economic disparities in crash data. Atlanta's network analysis showed that 88 percent of fatalities were concentrated in just 8 percent of streets, and that "neighborhoods with High-Injury Network streets had lower median incomes, a larger share of Black residents, higher rates of walking and taking transit to work, and lower rates of vehicle ownership," according to advocates at Atlanta Bike. Denver advocates found that areas designated "communities of concern" accounted for about 30 percent of the city's land area but 38 percent of all traffic deaths and 44 percent of pedestrian deaths.

Maguire notes that savvy local advocates have been among the biggest proponents of his own city's injury network, and that they've used the data to hold the city accountable for its Vision Zero failures.

"Our advocates regularly use the data to put pressure on us," he says. "And that's a very good thing."

As of now, city DOTs that make the data available are doing so out of the goodness of their hearts. High Injury Networks are not mandated by any state or federal law, and cities rarely face consequences for failing to collect that data — though some people think that should change.

"I bet every one of those cities [that doesn't have a High Injury Network] measures average daily traffic volume, and it's visible to the public," says Mike McGinn, executive director of America Walks. "They’re sharing these things because they believe that moving a lot of cars really fast is the core of their mission. If they thought their mission was safety, they’d be identifying those high injury corridors and prioritizing getting them fixed."

And when it comes to obligating cities to actually act on the evidence that some areas are worse for traffic violence than others, there's even less accountability. The Federal Highway Administration still allows states to set their own lenient safety goals for total annual deaths on their roadways — and there's no penalty for setting "goals" that are higher than the number of people who lost their lives in a previous year.

On the local scale, Washington, D.C. made headlines last week for passing a law that would require the Department of Transportation to submit plans to redesign the 15 most dangerous intersections in the district, but it may not actually require the city actually implement those redesigns in a timely manner.

That's why some advocates think that requiring High Injury Network maps are only the first step — and requiring real action on the basis of that data must follow.

"When you make that level of service the standard by which your road is measured, you have a situation where an engineer says, 'Well, I’ve gotta meet the design guidelines,'" said McGinn. "If we were to put teeth to this, we’d have the engineers who write the design guidelines to affirmatively put safety above everything. Theoretically, the right metric is the number of deaths and serious injuries — and the only acceptable answer should be zero."