An effort is underway to build a national network of connected walking and cycle infrastructure — and the organization behind it says a $10 billion federal investment in the project would help the country rebound from the economic ravages of COVID-19 in a way that highway spending never could.

Representatives from more than 160 organizations across America signed a letter to Congress urging leaders to pass a Greenway Stimulus, which would be used to build off-street trails, on-street bike lanes, and generous shared-use sidewalks to connect communities in all 50 states.

The coalition projects that the effort would create 170,000 jobs in construction and planning, and would generate up to $250 billion in local economic development. That's a 50 percent higher return on investment than most highway projects, according to the American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials.

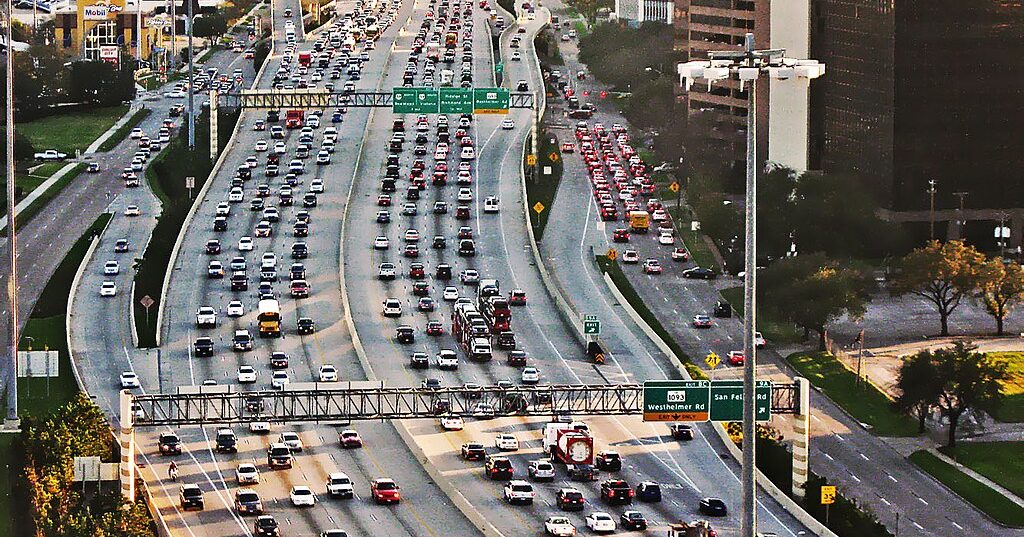

"Our nation needs to make the infrastructure investments that lead us to strong economic recovery and a healthy future," the Alliance wrote in its letter. "Expanding highways doesn't do it. The public is already showing us a path that does. People are using greenways and trails across the country more than ever as they strive to maintain their mental and physical health. Greenways have clearly gone from novelty to necessity."

The effort is being spearheaded by the nonprofit East Coast Greenway Alliance, which is developing a 3,000-mile, active-transportation route (with 1,000 miles of connected spurs) that runs from Key West, Fla., to the Canadian border in Calais, Me. Only about 33 percent of the route now is fully protected from car traffic, but the organization says the project is already helping to generate jobs and improve community health outcomes — and it could do the same in every state if it took the network nationwide.

"A greenway stimulus is an idea whose time has come, and now is the moment," said Dennis Markatos-Soriano, executive director of the Alliance. "The COVID crisis has proven that greenways are essential paths to healing. They’re not just paths to recreation; they’ve become necessary all over the country as sanctuaries of sanity, and havens of health. And these are equitable public spaces. Whether you have a job or not, you can get out and enjoy them."

Using federal infrastructure spending to stimulate the economy has long been an area of rare bipartisan consensus, but stimulus packages rarely include funding for active transportation, which is not typically framed as a major job-creator. Walking and biking infrastructure receives just two percent of federal transportation funds; many states don't even spend that much.

The signatories hope that a greenway stimulus could break that pattern because of its potential to economically benefit both rural and urban communities. Defined as "a corridor of undeveloped land preserved for recreational use or environmental protection," a "greenway" is a flexible concept, encompassing both gravel trails along decommissioned railway lines alongside bucolic cropland, like Missouri's Katy Trail, and urban linear parks like New York City's Highline.

In both contexts, studies have shown that greenways act as economic accelerants to their localities — and because greenway projects also tend to use other forms of active infrastructure to stitch together continuous routes between off-road projects, they can enhance a region's active-transportation network and cut greenhouse gas emissions at the same time. The Alliance says the combination appeals to conservatives and liberals alike.

"It’s a universally loved idea," Markatos-Soriano said. "Republican, Democrat, Independent; they all agree. "

Of course, greenways do have opponents — and not everyone wants to see the first major federal investment in active transportation spread along gravel paths countrywide, rather than concentrated in dense, urban areas, where it's more likely to help residents replace car trips.

Greenways also can face opposition from local residents, including fears about crime and privacy and distrust of top-down planning. Some worry that such projects might attract outside investment that could displace long-standing residents — or, conversely, could fail to make regions as prosperous as they were promised. The 20-year-old Katy Trail, for instance, brings $18.5 million per year to mostly-rural Missouri, but the bounty hasn't been shared evenly; many communities along the trail have failed to attract, fund or support tourist-focused businesses.

Still, proponents argue that, with intensive public engagement and careful planning, a national greenway network could benefit our transportation landscape and our economy — whether they're used for multi-state bike tours, or just a walk to the office.

“The value of [greenways] after this pandemic is going to elevate," Mitchell Silver, commissioner for New York City Parks & Recreation, said in a statement about the project. "This is not just a ‘nice to have,’ but now an essential and vital part of our civic infrastructure.”

A federal greenway act could catalyze a revolution in active transportation, proponents argue. Or, at least, it could help the U.S. re-center our streets around people, rather than the private automobile.

"We’ve seen for far too long that transportation has favored the four-wheeled vehicle," said Markatos-Soriano. "Greenways are an important part of undoing that; it’s not the one silver bullet, but it helps our country’s health, and it helps create equitable public space for everyone."

For more information on how to support the Greenway and samples of projects the Alliance tentatively plans to undertake, visit the website.