What would you do if your city built a comprehensive network of generous mobility lanes that were open only to bikes and scooters — but put them in the middle of the roadway, surrounded by fast-moving car traffic on both sides?

That unconventional "vehicular" approach to cycling infrastructure is on the streets now in Spain's capital city. And it may be starting to show safety and ridership dividends — enough that some American advocates are wondering anew whether the safest approach to building cycling infrastructure might be to build nothing at all.

Meet the Madrid Model

Since 2013, the city of Madrid has been quietly pioneering a new model of active transportation planning that shifts the focus away from building comprehensive networks of citywide bike lanes — yes, even those unprotected ones made of nothing but paint on the ground — and focuses instead on replacing high-speed driving lanes with "slow" lanes that are available exclusively to bikes, scooters, mopeds, and the driver of any other vehicle that's comfortable traveling less than 30 kilometers (about 19 miles) per hour.

Those slow lanes, though, are typically sandwiched between lanes of car traffic, even on major arterials — a counterintuitive choice that advocates say may actually make cyclists safer than they are on the edges of the road, where most traditional on-road bike lanes are located.

The combination of these two unconventional approaches is being called "the Madrid Model," in contrast to the beloved Amsterdam model of robust, connected networks of protected bike infrastructure that removes riders from the car-dominated roadway altogether.

American advocates of "vehicular" cycling — and even some who are just tired of transportation leaders painting sharrows on high-speed roads and calling themselves bike-friendly — are excited about the potential.

"[Most people] don’t understand the consequences of riding on the edge [of the street]: The close passing, insufficient buffer space, inconsistent available width, debris hazards, and lack of vantage around corners," John Allen of the cycling education nonprofit Cycling Savvy wrote in a blog post. The organization has publicly applauded the Madrid Model for its "outside the box" approach to mobility safety, and expressed cautious optimism that it could become a strong option on U.S. soil, especially if we continue our seemingly relentless march towards autonomous vehicles.

The only question is whether the model works — and who it really serves.

Madrid's accidental mobility model

For their part, Madrid's leaders didn't exactly set out to create an approach to non-driver safety that intentionally addressed disparities in cycling — and the success it has had is a bit of a happy accident.

In 2013, the Spanish capital faced a steep fine from the European Commission if it failed to take meaningful action to curb transportation emissions — but due to the brutal double-blow of the ongoing global real-estate crisis, whose worst shockwaves hit Europe in 2012, and an expensive failed Olympic bid in the same year, leaders had little money for large-scale sustainability projects. Unable to afford spendy interventions like transit enhancements or a large network of protected bike lanes — but skeptical that Madrileños would use unprotected bike lanes at all — the city gambled on the largely untried "slow lane" model," which required little more than paint and basic planning.

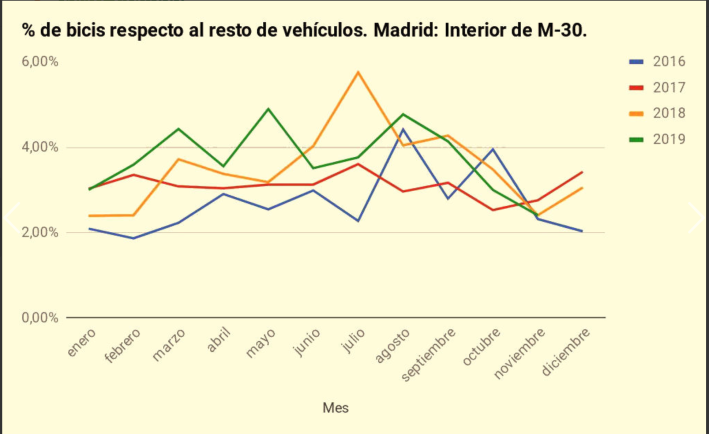

The new lanes were paired with enforcement for drivers who broke the 30 KmPH speed limit in those lanes, as well as a new e-bike share program to encourage would-be riders to conquer the hilly city on two wheels. And in time, the city did experience a gradual increase in the share of bikes on the road, peaking at 6 percent by 2018. (By contrast, fewer than 1 percent of U.S. trips are taken by bicycle.)

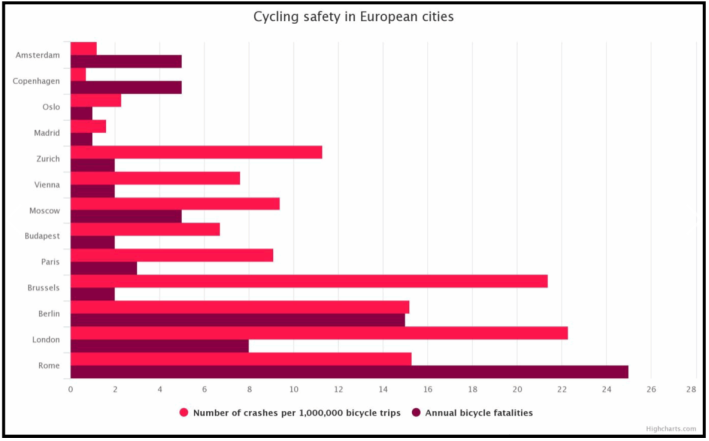

Advocates think the approach may have saved lives, too. By 2018, Madrid had one of the lowest rates of cycling fatalities in Europe, behind only Amsterdam and Copenhagen, and slightly above Oslo, which eliminated traffic fatalities completely the next year. All three of the European cities boast some of the most impressive networks of protected bike lanes in the world — the exact opposite of the Madrid model.

By the time the economy recovered in 2018, Madrid implemented a much more comprehensive pollution reduction program that including banning non-resident car traffic from the city center — but proponents stress that most of the cycling wins prior to 2018 may be attributable to the slow lane model.

Who is the Madrid Model for?

What proponents of the Madrid Model lack, though, is the kind of comprehensive data that could prove the unconventional strategy is serving all of the city's citizens — or even improving matters much on key safety baselines.

Much like most U.S. cities, Madrid relies heavily on manual cyclist counts occurring on just one day of the year at a few fixed points throughout the urban grid. There's also a paucity of easily accessible data on cycling fatalities from any year, because the country's otherwise voluminous crash statistics are not disaggregated by transportation mode at the city level.

So aside from a handful of occasional snapshot studies commissioned by international groups like Greenpeace, advocate groups like Madrid Ciclista have struggled to make the case with data that cycling safety in the city has improved at all — just that it was pretty good in 2018, after five years of the slow lanes program, in addition to the implementation of e-bike share and other possible interventions that have not been the subject of rigorous analysis.

Nor does the scarce data address the crucial question of who is using the new lanes, aside from able-bodied, fearless, disproportionately male and white cyclists who are more often willing to bike while surrounded by traffic. As impressive as Madrid's rise in biking mode share number might seem, that actually has more to do with declines in car use than rises in biking: cycling adoption on the whole has only risen by about one percent citywide since 2013.

Amsterdam vs. Madrid

Both these facts might seem like a blow to vehicular cyclists, who have long faced criticism from street safety advocates — including some in the Streetsblog network. And the hard truth is, most data — scant though it is, at least when compared to the endless traffic studies we commission in the name of driver safety — simply doesn't support the idea that cyclists are somehow safer when sharing the lane with drivers. One U.S. study even showed that streets with protected lanes have lower crash rates for both cyclists and motorists— a huge score for team Scandinavia.

But proponents stress that the Madrid Model is not exactly the hardcore, anti-bikeway model lauded by controversial vehicular cycling advocates like the late John Forester — because slower modes still have a dedicated lane, albeit an unprotected one riders have to enter by passing through a driving lane first, as they do at traditional intersections. And these same advocates argue that putting bikes in car traffic is the only way to send a clear message that bikes, themselves, are a part of traffic — and deserve all the privileges and legal protections afforded to drivers.

Regardless of how the debate shakes out, the all-but-certain impending global recession might decide the matter for us. That's because the Madrid model is so inexpensive, some advocates predict that cities who want to build a comprehensive network of designated cycling spaces may soon have no choice but to choose it, or else do nothing at all.

"The [Scandinavian] models...made sense in the era of automobile expansion, when it implied progress," says Madrid Ciclista in its incendiary description of the Madrid Model, translated here by Streetsblog. "Now society has realized how impractical this conception of mobility is, and therefore this scheme is becoming obsolete. Cities like Amsterdam are... slaves of their past and cannot renounce the model that defines them, that is why they will be the last to join the trend that Madrid is setting and which will be the majority in Europe in a few years."

It's up to Americans to decide whether such a future would be a dream, a nightmare, or, more likely, simply better than what we have now — which is next to nothing.