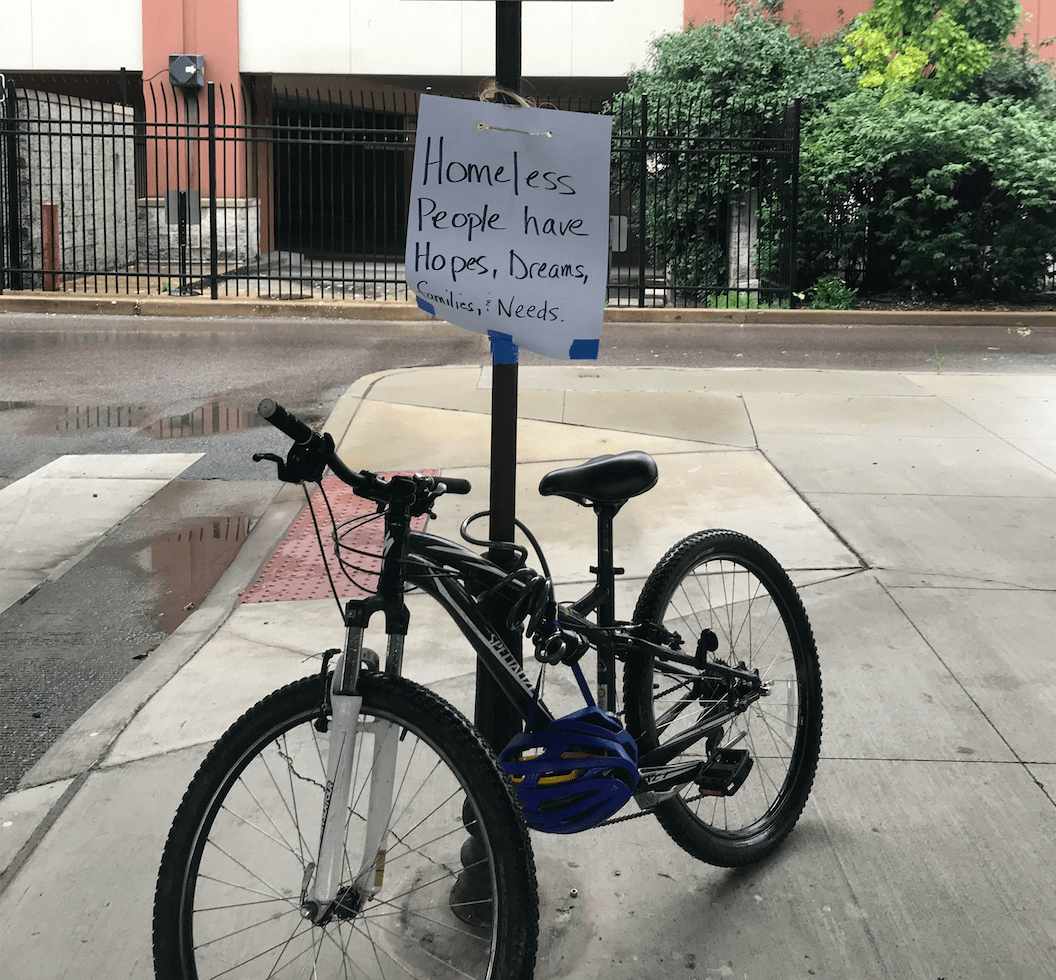

The Missouri Department of Transportation is using street safety concerns as a pretext to aid the forcible evacuation of an encampment of unhoused people under a highway overpass in St. Louis — raising specific questions about who, exactly, the city's "traffic safety" efforts are for, and larger questions about transportation agencies' role in perpetuating violence against unhoused people across the U.S.

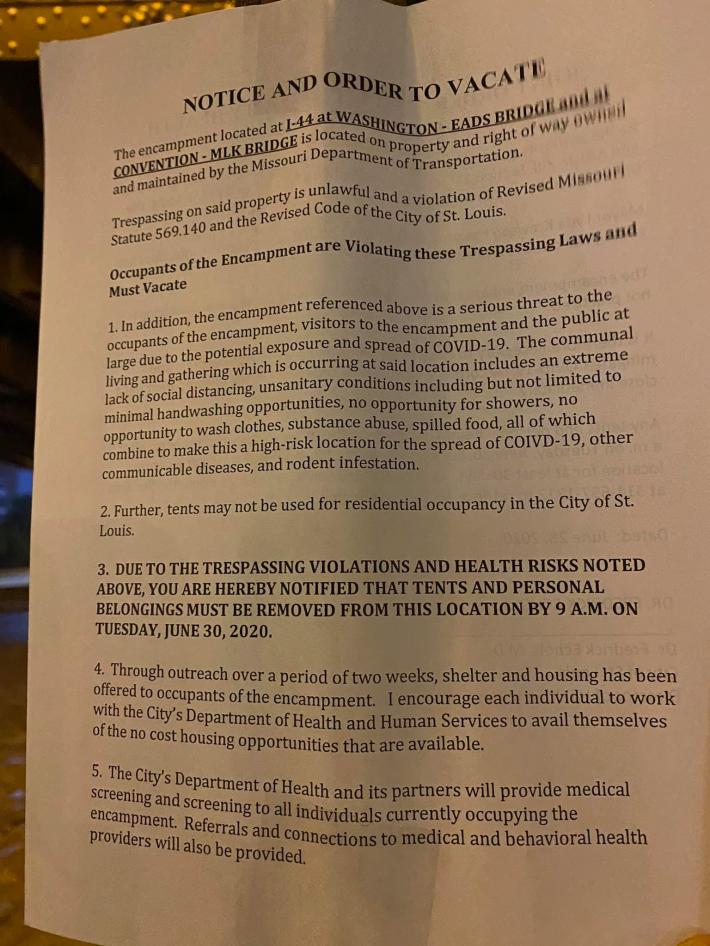

Late last week, representatives for the state agency ordered a community of unhoused people underneath a Highway 44 overpass to vacate by June 30. Residents report that the representatives posted the message on nearby poles and immediately left the area, and did not offer the unhoused people resources to access alternative shelter before the deadline.

MoDOT explained its involvement as a matter of public safety — claiming residents of the camp had been burning trash in fires, and alleging that smoke from those fires might pose a visual obstruction to drivers on adjacent roads. (MoDOT did not return a request for comment as to whether any drivers had reported the smoke as a safety hazard.)

Advocates questioned why the city elected to prioritize the safety of drivers over the safety of unhoused people, but MoDOT St. Louis District Engineer Tom Blair defended the decision with the following statement, which was widely interpreted as putting property over the well-being of vulnerable individuals:

As the Department of Transportation, we need to address safety risks that these individuals are creating to MoDOT property, and to the traveling public, as well as their own safety, as quickly as possible while still accounting for the occupants.

When a highway becomes housing

It might seem hard to believe that an exhaust-clogged strip of concrete under a downtown highway is one of the safest and most stable forms of housing available to unhoused St. Louisans. But transportation infrastructure has long doubled as shelter for the disenfranchised — thanks to a system that fails to provide good alternatives.

"Many of the residents here want to stay here because a lot of them can’t survive in the shelters the city provides," said Alex Cohen, an organizer for Tent Mission STL, a coalition that provides support for the unhoused during the coronavirus pandemic. "[Here under I-44], they can meet with service providers like us; we're out here seven days a week. They can access harm reduction resources. And the highway is actually a really great shelter, when you think about it. I mean, it’s pouring rain right now, and look — we're not wet."

By contrast, Cohen describes the conditions at St. Louis city shelters as "jail-like." Advocates report that St. Louis city shelters offer little medical support, especially for those who might be intravenous drug users or suffer from post traumatic stress disorders that are triggered by past trauma they've experienced in city housing, or in crowded bunks they slept in during their military service. (The Department of Human Services did not respond to a request for comment.)

And residents of the camp are simply anxious about the risk of getting COVID-19 in a crowded indoor setting where the virus thrives most.

"A lot of the residents here have been told that since there are more than six people under the overpass, it’s impossible to social distance, so the city has to take action," Cohen says. "Which is pretty interesting, because one of the main intake shelters that the city uses — the Buder Recreational Center — is a congregate shelter that sleeps 28 people in a small, indoor gymnasium."

Other camp residents do want to make use of city shelter resources, but they're wary of the city's ability to provide them with stable housing for the long run. If the threatened Highway 44 camp eviction happens, it will be the third time that many people who live under I-44 have been forcibly vacated from city property since the COVID-19 pandemic began — and though most were initially relocated to city shelters, many soon found themselves unhoused again when the city reportedly lost its contract with a Red Roof Inn that had agreed to serve as a temporary shelter during the pandemic.

When seen in the broader context of a public realm that ruthlessly polices parks, uses hostile architecture to discourage behaviors like public sleeping, and has closed countless public libraries and other public, indoor spaces due to COVID-19, it's not hard to understand why a highway overpass could be seen as an unlikely form of sanctuary. As advocates for active transportation know all too well, car-focused infrastructure is one of the few public services that has, historically, gotten robust government support — even as other city services have been defunded.

The Department of Human Services receives just 0.2 percent of the St. Louis city budget.

When existing on the street becomes 'trespassing'

Even those residents of the I-44 encampment who would welcome a bed in a city shelter say the city hasn't offered them one — and in the meantime, they're struggling to survive being declared trespassers on one of the last scraps of public space left available to them.

"I’ve been out here for two months now, and four days ago, MoDOT suddenly put up all these 'no trespassing' signs," said Nikkie, a camp resident who preferred not to give her last name. "Well, you’re standing here right now; are you trespassing? How do police decide who to ticket and who not to ticket? You probably wouldn’t get a ticket for just standing there, but I would, and I’ve been here since before the signs went up. Is that fair? No."

Like many of the residents we spoke to, Nikkie questions the logic that the city is evicting her from the camp for her own safety; many suspected the upcoming Fourth of July holiday, which is expected to bring tourists to the nearby Lumiere Casino, has more to do with it. (Alderman Jack Coatar, who represents the ward, could not be reached for comment.)

"Whenever there’s a major holiday or a major event, [the police] will go around and pick up people who they know have warrants, just for petty stuff, just to keep them in jail for the weekend of the event," said Nikkie. "Cops have said stuff to me like, 'You’re the first thing that people see when they come from out of town. We can’t have that.'”

Nikkie says these warrants are largely for nonviolent offenses like panhandling, which many residents turn to when they struggle to access or can't trust traditional city support. She estimates she's gotten 50 tickets for panhandling in the last year, but a volunteer attorney is helping her to get them dismissed.

"My lawyer tells me that what I do is not illegal, because I don’t actually ask anyone for money," Nikkie said. "Standing there with a piece of cardboard not hurting nobody, that's actually not panhandling. That’s just free speech."

The criminalization of simply standing on a street while holding a sign, of course, has deep similarities to other street "crimes" whose enforcement has little to no proven benefits to public safety but are often used as a pretext for police harassment, like "jaywalking." Many advocates argue that it would be better if police were kept out of most responses to unhoused populations — or at the very least, simply made use of the wisdom of the grassroots outreach workers who know the unhoused community best.

"I’ve never had city workers engage with me about what the medical needs of the unhoused are," said Thomas Van Horn, a medical student who volunteers with nonprofit The T, which provides treatment and hospital referrals to unhoused St. Louisans in the I-44 encampment, among other services. "It just doesn’t seem to be a priority. People say these departments can't do real outreach, because they have their hands full with COVID; I say, if they have their hands full with COVID, they should be prioritizing people who are at the highest risk for COVID, which are the unhoused — and not throwing them out of their camps.

"These people won't just be displaced," he added. "They'll be dispersed, and we won't be able to find them as easily." The Centers for Disease Control explicitly warns against shutting down homeless encampments during the pandemic for exactly this reason, noting that dispersement can "break connections with service providers" and "increase the potential for infectious disease spread."

The City of St. Louis has not responded to a request for comment as to why it is breaking with CDC guidelines and clearing the I-44 encampment anyway. And advocates say they're not the only city government to break with federal wisdom and put unhoused people in harm's way.

"Nationally, this is happening everywhere," said Van Horn. "It’s not unique to St. Louis."