Getting behind the wheel has become a new form of "outdoor" recreation during COVID-19.

Evidence is emerging that erstwhile pedestrians are choosing the Sunday drive over the socially distanced hike, opting for safety from the virus inside isolated automobiles rather than the presumed danger of passing an infected stranger on a walk in the great outdoors.

It's unclear how much of the slow rise in driving is due to frivolous trips, but some part of it clearly is: total vehicle miles traveled has been on the rise for weeks, long before most states ended their lockdowns and gave residents anywhere to actually go.

According to traffic analytics company Streetlight Data, national vehicle miles traveled hit a historic low around April 12, but began to climb steadily after that, even though no state began re-opening its non-essential businesses until roughly April 30. By May 15, traffic volumes had risen over 200 percent from that Easter nadir in some counties, including vacation destinations like Cape Cod and York, Maine, even though their respective states remained under shelter-in-place orders and beaches (and their parking lots) remained closed.

Advocates argue that these increases in driving are too large to be explained by a few extra trips to the grocery store — and anecdotes support the idea that pleasure driving may be on the rise. When Streetsblog reached out across social media, we received a flood of responses indicating that people are, in fact, driving for fun:

"I take tiny drives for a change of scenery when my partner is doing a virtual gaming gathering with his friends, which can get noisy," said Gigi of Seattle. "Otherwise, I might have gone out for coffee, or to a library."

"I just drove for fun," said Eszter of Denver. "Bought a random salad and now I’m eating it in the parking lot of my empty campus, where I have no official business."

Sasha of Madison, Wisc., had an even simpler response: "Yes. Every single day. I mostly just park somewhere nice and read."

Almost none of the people who answered our open question had been pleasure drivers before the pandemic; some had even been transit commuters. Certainly none of them were hardcore car enthusiasts like the author of this truly boggling personal essay from Autoweek, whose abiding love for his Ram Rebel 4x4 lead him to muse openly about whether driving wasn't nearly as dangerous as... making French cuisine:

I was also not fully buying that driving per se risks overburdening EMTs or hospital personnel...One might just as well fall off a ladder while performing that long-delayed home project, or slice a finger while attempting beef bourguignon, and end up in the same ambulance and emergency room as a driver. Should we stop wielding kitchen implements as well?

(Don't worry, an ethicist clues him in about the 1.35 million global road fatalities and the existence of the global oil industry in the next paragraph.)

But as the COVID-19 lockdowns ease — and, more than likely, will be put in place again — the pleasure drive threatens to become a feature of daily life even for currently car-averse Americans. And it doesn't have to be that way, if we take the time to confront the structural reasons why so many of us are driving around aimlessly — and put some simple policies in place to give our neighbors safe and meaningful alternatives.

The origins of the pleasure drive

The notion of the Sunday pleasure drive might have seemed quaint and nostalgic just a few months ago, but it's been a fixture of the U.S. culture for a while — and its origin, surprisingly, has a lot to do with the bicycle.

The Federal Highway Administration traces the birth of the scenic byway — a road whose primary purpose is sight-seeing, not transportation — to the Good Roads Movement of the 1880s, which was spearheaded by velocipede advocates who were tired of getting thrown over their handlebars on uneven country roads, and wanted to have nicer picnic sites to cycle to on their weekend jaunts. Their efforts eventually lead to the creation of the first state highway agencies in the 1890s, as well as the construction of the first explicitly scenic (and evenly paved) byways in the early 1900s.

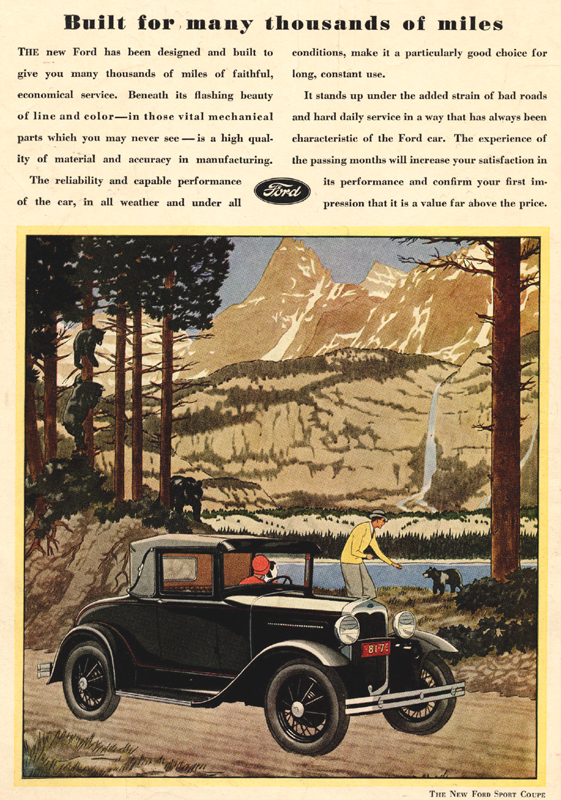

But those idyllic bike parkways were soon co-opted by a new mode of transportation — the Model T, which was introduced in 1908. Henry Ford was reportedly an early advocate of the Sunday drive (on every day of the week, natch) because it drove sales. As scenic byway construction and designation was expanded at the federal level (fun fact: it's still expanding today, and byways are still eligible for special federal dollars), car companies doubled down on the image of the driving as a pleasurable activity unto itself, rather than simply a tool to get drivers where they needed to go.

'A large metal rolling isolation chamber'

But pleasure drivers didn't stick to the pedestrian-free mountainside parkways, of course — and they still don't. And as cars increasingly became a prerequisite for participation on public life, the infrastructure those cars demanded also swiftly eroded the basic public spaces where people could safely travel, recreate, and simply take pleasure outside of the protective bubble of the automobile — without worrying they'd be maimed or killed by a driver.

That dangerous reality has even higher stakes during the COVID-19 pandemic. On a recent episode of The War on Cars, co-host Sarah Goodyear expressed an apt anxiety that the car might come to be seen as "the ultimate PPE": a physical, steel-and-glass barrier on wheels that's better at stopping the transmission of the virus than any N95 mask. Andrew Clark of the Globe and Mail called it "a large metal rolling isolation chamber" — and actually meant it as a term of endearment during this bizarre historical moment.

It should not surprise us that pleasure driving is on the rise in an era when using public space puts people at risk of a deadly disease. It should surprise us even less when that same pandemic has claimed third places like coffee shops and libraries and beaches, shutting them down outright or allowing them to re-open with too-often insufficient social distancing practices. And it should definitely not surprise us considering that, for people of color, the disabled, and the otherwise disenfranchised, the virus is just yet another barrier piled upon many other long-standing barriers to public and private space — barriers like structural racism, police brutality, ableism, and hate. We cannot talk about the reformation of public space without addressing those core concerns.

Of course, we can create alternatives to pleasure driving by simply making our streets accessible to all by fixing the unique barriers faced by all road users. We can build third places on our streets and expand our parks and end traffic violence forever. But we have to start now – and it won't be as easy as taking a Sunday drive.