Three Midwestern members of Congress are pushing for a new bailout for American automakers — seemingly forgetting the economic and safety disaster that ensued the last time they rescued the automotive industry, during the 2009 financial crash.

Reps. Marcy Kaptur (D-Ohio), Debbie Dingell (D-Mich.) and Fred Upton (R-Mich.) sent a letter to their fellow lawmakers last week urging them to include the automobile industry in the next COVID-19 relief package. The Rust Belt renegades argued that urgent action was needed to safeguard the jobs of 10 million workers employed across the industry, as well as to prevent a cascade of economic hardships that could result from the collapse of an industry that's responsible for 3.5 percent of the nation's GDP.

The letter, ostensibly, did not call for funds to re-train automotive workers for employment in transportation industries that don't kill tens of thousands of Americans every year, like high-speed rail construction; not did it factor into the hard costs of car dependency to our society into its economic arguments, from climate change to car crashes and beyond.

Moreover, the automotive industry was already granted relief through the most recent federal COVID-19 relief package, the CARES Act, mostly in the form of steep employee retention tax credits and the suspension of the employer share of payroll taxes, as well as paycheck protection loans to dealerships and smaller suppliers of auto parts. The receipts for how much the entire industry received won't be tallied up for a while, but these members of Congress are already saying it's not enough because the biggest automakers weren't eligible for many CARES Act programs. The lawmakers are lobbying for a dedicated aid package for the industry, likely at a far greater scale than the paltry $25 billion granted to all of the nation's public transit systems.

But here's the difference: public transit is an essential public service that was drastically underfunded even before COVID-19. And automakers are private companies that have gotten unusually robust federal support for years — to dubious benefit for anyone but the automakers themselves.

During the Great Recession of 2009, the three largest American auto manufacturers alone received $80 billion in favorable-term loans as part of the Troubled Asset Relief Program (whether they ever really paid them back is doubtful), in addition to funding the $2.8-billion "Cash for Clunkers" initiative to incentivize new car purchases. Those investments had a staggering impact — and arguably, not a good one.

Since the bailout:

- traffic deaths experienced the largest two-year increase in more than half a century

- gasoline consumption increased after five consecutive years of decline

- there was a sharp (and still rising) increase in greenhouse gas emissions during a period that scientists believe was particularly crucial to our climate future

- the failure to re-train workers for rail projects further continued auto-centrism in the nation's transportation mode share, which ...

- ... increased the likelihood of sprawl-style development rather than urban infill

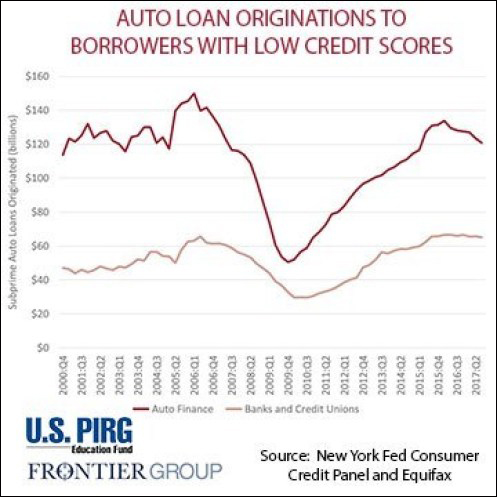

- and, finally, the nation experienced an auto lending crisis that continues unchecked today.

All of these bullet points represent critical failures of policy that Streetsblog will be addressing going forward.

For now, let's focus on the auto-lending element of that litany of outrages because it remains particularly under-discussed in the many, many otherwise comprehensive retrospectives about the failures of the 2009 bailout. R. J. Cross, policy analyst at the Frontier Group, summarized the complex history eloquently, so we'll quote her at length:

One recipient of the federal government’s efforts and auto bailout package wasn’t a car manufacturer, strictly speaking. While most of the $80 billion allotted for the industry’s rescue went to General Motors and Chrysler, $17.2 billion of the federal relief package was awarded to GMAC, General Motors’ financing arm (now Ally Financial), enabling the company to restore the flow of credit to would-be car buyers. Later, Chrysler’s financing arm would also receive bailout money.

Soon thereafter, the lending companies loosened their lending standards – a move that was soon followed across the auto finance industry. GMAC was the first financial institution to publicly state it would use its bailout money to offer credit to consumers, lowering the minimum credit score to qualify for financing from 700 down to 621 – nonprime levels. GM began pushing zero-percent and low interest financing, particularly on its largest – and most expensive – gas-guzzling truck and SUV models. The larger and more expensive the car, the higher the price tag, and the more debt you take on to buy it.

The federal government’s efforts to get Americans to buy cars didn’t end there. The federal government also began to back all new car warranties. And the 2009 economic stimulus bill even allowed those spending up to $49,500 on a new car to deduct all sales and excise taxes from their federal income taxes.

All of these efforts to get Americans to buy cars – and help to resuscitate the dying car industry – worked like a charm. New car sales surged, with an unprecedented streak of seven straight years of sales increases...

[But today,] more Americans than ever are dealing with the financial hangover from the debt they took on to drive auto sales to new heights. Delinquencies rose – and are still rising – as are car repossessions. Millions of Americans carry debt that will constrain their financial freedom for years to come.

If we truly valued freedom – including the freedom to avoid the burden of debt to own a car – could we have responded to the Great Recession in a different way: one that didn’t result in further cementing dependence on cars?

Could we have increased investments in public transit, perhaps, or made more of our communities places where people feel safe to walk and bike to work? Could we have “reinvented” the auto industry such that it didn’t require debt and the financial insecurity of millions of Americans? Could we have started a conversation about what true freedom means – both for transportation and our economy?

It’s not too late for that conversation to begin.

We couldn't agree more — and when it comes to the automotive industry, we can't afford to treat our current recession the way we did the last one. COVID-19 can be our opportunity to break with car culture once and for all — but first, we have to stop bailing out a sector of our economy that is cancer on the safety, health, and equity our country purports to value, and put every penny of that money towards retraining workers in industries that aren't.