Transit ridership has been declining nationwide, but transit agencies can win them back with more frequent service and a focus on safety, reliability and cleanliness, a new report argues.

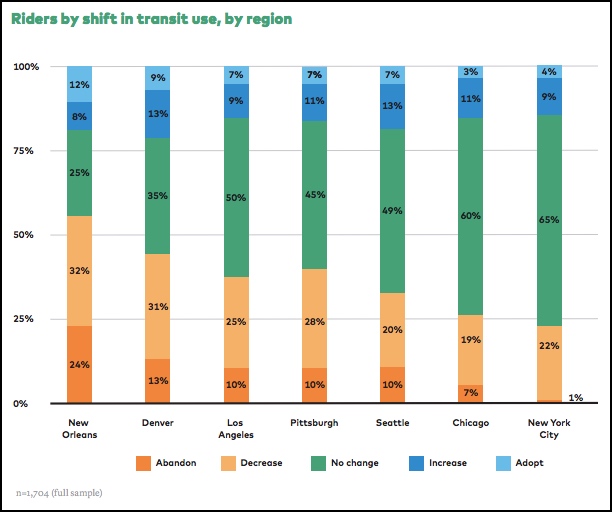

TransitCenter surveyed more than 1,700 transit riders in eight cities to learn what's luring riders away from transit. The reasons for (and the amount of) the decline vary by region, but some central themes emerge:

Cheap cars

The key thing that predicted when a transit rider would stop using transit, or use it less, was buying a car. Lax auto lending standards have made car ownership — even for lower-income people — much more accessible in the last few years and that seems to be playing a key role in the decline of transit ridership.

And the increase in car ownership is staggering: In the 2016 version of the survey only 43 percent of respondents said they have sole ownership of a car. That number is now 54 percent.

About a quarter of the decline in transit ridership was people just walking away from transit entirely. But most of the decline could be explained by less frequent use. Those who had increased their access to a car since 2016 rode transit on average six fewer days a month.

Gentrification

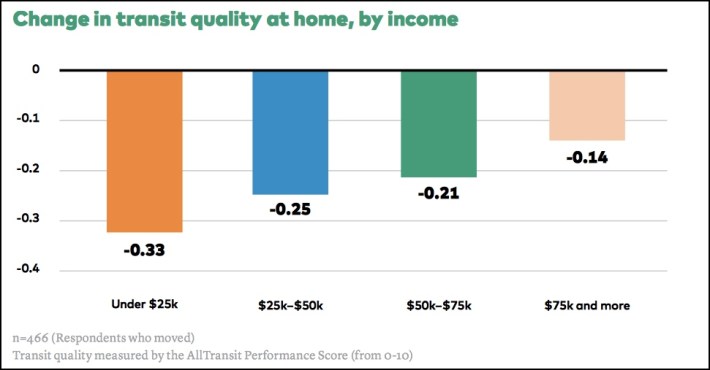

Another big factor seemed to be gentrification. Where you live — and the level of transit service provided there — is a key determinant of who will ride transit.

Unfortunately, survey respondents with incomes below $75,000 were twice as likely as higher-income respondents to say "wanting cheaper housing" was their reason for moving.

"The lowest-income respondents endured the greatest loss in transit quality after moving," authors Steven Higashide and Mary Buchanan wrote. "Their lesser transit access at their new homes is similar to transit in Baltimore, Maryland, compared to Washington, DC, or that in Astoria, Queens, compared to Midtown Manhattan: a marked decrease in quality arising from lower frequency, fewer routes, and less within reach of transit."

Chicago, Pittsburgh, Seattle, and Los Angeles showed the greatest decline in transit access for lower-income movers.

Uber and Lyft

The presence of Uber and Lyft also seemed to have an impact — although less than private car ownership.

Some survey respondents reported using it as a complement to transit — for example for a last-mile connection or for one leg of a transit journey.

Transit riders were much more likely to use Uber and Lyft than those who did not use transit overall.

Transit riders who started using Uber and Lyft reduced their transit ridership by about 6 percent, the survey found. In addition, Uber and Lyft seemed to be a factor for some people in deciding to purchase cars. Of the survey respondents who said they bought a car between 2016 and 2018, 7 percent said they did so to drive a car for either Uber 0r Lyft.

For transit ridership that substituted Uber and Lyft for the bus or train, "slow speeds, limited hours of service, unreliability, and too few stops or stations" were the main reasons given.

How to improve

The best antidote to declining ridership is better service.

Los Angeles, Denver and New Orleans had greater ridership declines over the study period than Seattle, which has been investing in improving service frequency on buses.

Among the factors cited as most important to riders were service frequency, crowding reliability but also cleanliness and safety. Safety was especially important to women.

Interestingly, the price of ridership — fares — was a relatively low concern compared to the more nuts-and-bolts aspects of service quality. Even low income riders rated frequency, crowding, safety and reliability as more important than fare price.

"The notion of making transit 'free' — though politically appealing — would provide less utility to the public than if the equivalence in foregone revenue were spent improving service and continuing to charge a fare," the authors wrote.