The "Hub of Hope" inside a Philadelphia subway station is a shining example of a new model for transit agencies in dealing with homeless passengers — one that focuses on solving the core problems rather than repeated arrests.

The Hub of Hope is a partnership between the transit agency, SEPTA, and Project HOME, a social service agency for unsheltered people. SEPTA provided the space — a renovated 800-square-foot storefront inside the underground rail station at Penn Center downtown.

And Project HOME, using paid employees and volunteers, provides a place to hang out and get connected with services in a non-judgmental atmosphere — plus plenty of free coffee and food.

"We need to be where the people are," said Carol Thomas, the organization's director of outreach, told the audience at the Railvolution Conference in Pittsburgh this week.

In 2012, Project HOME and other advocates counted about 200 living in the bowels of the city's subway system.

Dealing with homelessness is a tricky issue for transit agencies. But one that is getting increasingly difficult to ignore.

New York City's "homeless sweeps" of the subway stations, have brought the problem into focus. But many experts say those kind of punitive tactics are futile.

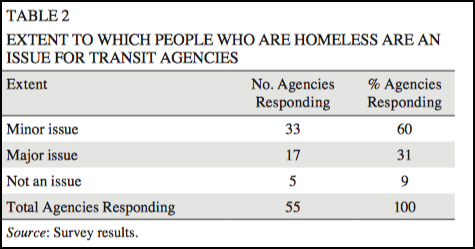

Dan Boyle, a planning consultant, published a study in 2016 looking at how 55 agencies are addressing the problem. His survey found that homelessness is a problem for almost every transit agency, but it is more acute for the biggest operators.

About 75 percent reported they partner with other agencies — law enforcement agencies, social service providers or homeless shelters — on the issue. The reported results were mixed-to-positive.

In his review of best practices, Boyle called on-site drop-in service centers like Philadelphia's Hub of Hope one of the most promising strategies.

Trained social service workers know how to spot the "treatable moment," where someone struggling with mental health problems, or addiction might be willing to accept some kind of intervention.

"The ability to do client intake on site at the transit station or center is very effective in persuading people who are homeless to seek and accept help," Boyle wrote.

Homeless people are attracted to transit for a variety of reasons. Transit agencies themselves can't solve the problem of homelessness, but they can, with the right policies, create a safer and more comfortable environment for all users. And assist people who need help, says Boyle.

"Transit police are unanimous that enforcement will never solve the problem. They were unanimous," Boyle said at the Railvolution conference. "Building partnerships with service agencies is a way to begin to get a grip … on this problem."

The problem has become increasingly urgent for Bay Area Rapid Transit (BART) as housing prices in the Bay Area have skyrocketed. BART Group Manager Tim Chan has been leading an effort to retool station design in a way that minimizes conflicts.

Station design has a limited impact on the problem, but it's important for designers to keep the issue in mind, he said.

"The more walls you have, the more hiding spaces you have, the more people feel tense," he said.

"A lot of our customers will say, 'Just kick them out,'" Chan added. "But the homeless have civil rights. What you have to do is target the behavior."

Increasingly, unsheltered people have been camping at the bottom of the stations. Debris, including needles and excrement, have been getting into the escalators and presenting hazards for station workers.

In response, BART has added locking canopies that protect the escalators at night. The change is credited with a 36 percent reduction in breakdowns, Chan said.

To address sanitation and hygiene issues, BART has also started opening up formerly locked restrooms in stations across San Francisco. The restroom hours, however, have to be attended by staff, says Chan. The effort, called the Pit Stop partnership, also receives support from the city of San Francisco.

Then there's the question of policing.

In Minneapolis, the Metro Transit police spend an increasingly large portion of their time responding to calls, according to Police Lieutenant Mario Ruberto, who also presented at the conference.

Just a few years ago, Metro Police were receiving about 1,200 calls each year to respond to situations involving homeless riders. This year, said Ruberto, they agency will surpass 3,000.

When Ruberto first joined the force, 14 years ago, the police response was mostly just to arrest homeless people for trespassing. But court decisions have limited the legal authority for transit agencies to do that. It was also counterproductive.

Ruberto has an unusual background for a police officer. Prior to joining the force he spent two decades as an EMT and a nurse. He would recognize that some of the people being stopped were struggling with serious issues.

"Chronic health conditions, serious mental illness, substance abuse: It’s not easy for standard cops with no medical training to figure out all those things," he said.

"I said I need more help. I need some outreach workers."

Eventually Ruberto's supervisor let him take on the issue as part of a "problem oriented policing project." Thirty days ago, he finally got his wish: $1 million for a program involving five specially trained police officers. In addition, the agency was able to work with the housing authority get control of 89 vouchers for subsidized housing that it can give to the homeless, who would then have to find housing themselves.

One of the big problems in Minneapolis is weather related, say Ruberto.

For example, during the Super Bowl last year, the city closed its system of above street "skyways," sending homeless people flooding out into the streets at -6 degrees, and then onto the transit system. About 50 additional homeless people piled onto Metro's railways and trains during the event, he said.

The shelters were full. It's dangerous to send people out into weather that cold.

"We really have very few options. We can take them to the emergency room, to jail or detox, or leave them on the transit system

"If the shelters are full they’ll give them passes for transit," he added. "It puts us in a very difficult situation."

About 200 people use the Twin Cities Metro for shelter every night, according to official estimates.

But thanks to the work of Ruberto and others, Metro will now have 25 beds in a new 50-bed Winter Safe Space shelter, Ruberto told the audience.

"We need to have sheltering and we need to have options at night," he said. "Without the additional shelters, we’re always going to be the place they turn to."

In Philly, Hub of Hope helped place 359 people in shelter, treatment or other housing options just within the two-month span of February and January 2014, according to Boyle's research.

"Our goal is to end chronic street homelessness," said Thomas. "How do you end homelessness? Housing."