It's too early to tell whether Vision Zero will ever reach the goal implied its name, but there's one way to give it a good chance: getting drivers to slow down.

That's emerging as a crucial goal of the Vision Zero Network, a national group that help cities implement safer street practices. The non-profit organization, which gets funding from Kaiser Permanente and restaurateur Bill Russell-Shapiro, is ramping up for a new speed-focused campaign, having just hired Veronica Vanterpool, former director of the Tri-State Transportation Campaign in New York, as deputy director.

Vanterpool and Director Leah Shahum talked with StreetsblogUSA about the Vision Zero Network's vision going forward. The interview has been edited lightly for length and clarity.

Streetsblog: So you've made a big new hire. What's next for the organization?

Leah Shahum: We’ll continue to promote Vision Zero and defend against those places where they’re treating it simply like a tag line or a PR campaign. To actually make progress or commit to Vision Zero, it will really take a transformative shift in how your city is prioritizing safe mobility.

We're also going to be focusing more on the importance of speed management. We, as a society, need to be paying as much attention to the issue of managing speed as many communities have done around drunk driving. The level of change in government over the last few decades, thanks to groups like MADD, has resulted in a sea change in how people think about drunk driving. We need to have that same sort of focus on managing unsafe speeds.

We're going to try to help cities actually move forward with strategies that effectively reduce speeds in their communities, whether that's lower speed limits, more automated enforcement or engineering changes.

Another big focus is equity. There are some positives in the sense that Vision Zero is very data driven and can help highlight systemic inequities in our transportation system and beyond. More and more people are recognizing that not all communities have been treated equitably when it comes to safe transportation investments.

At the same time, there are real worries about the role of enforcement in this county today. How do we help Vision Zero not become an opportunity for over-policing in certain communities that are already under duress in terms of racial profiling and police bias? That is an important piece that we want to help cities improve through their Vision Zero efforts.

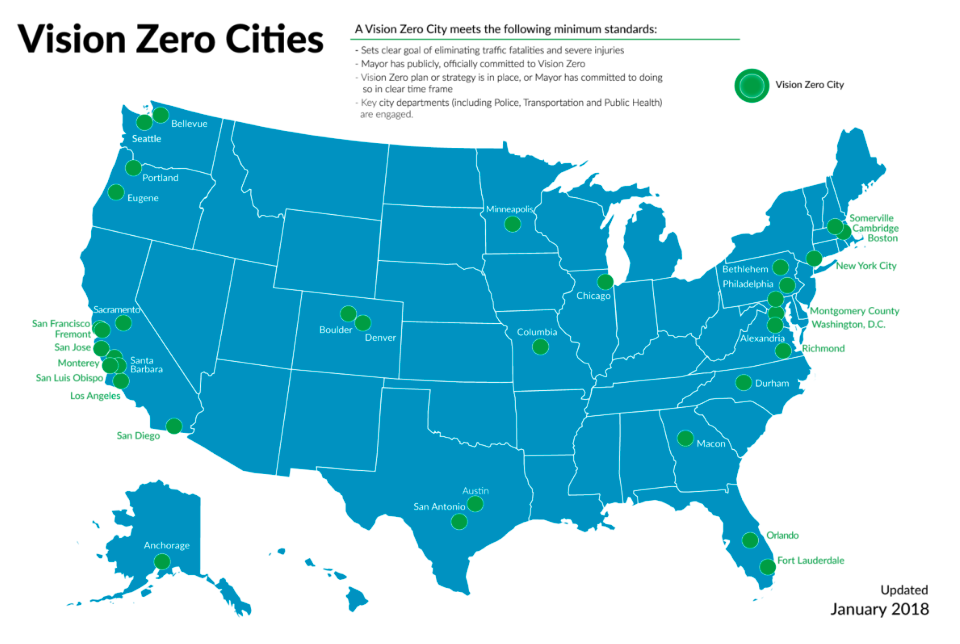

We're also getting ready to release a set of standards for Vision Zero this fall. How do we help people understand what Vision Zero entails? This will be the first time there will be guidelines that explain this for U.S. communities.

Can you provide an example of what that would entail?

Shahum: One of them is: System designers and decision makers advancing cross-cutting measures to reduce car dependence, improve transit, and promote walking and biking. This is an area where the Vision Zero movement in the U.S. has not been as strong as we could be. Some of the strongest predictors of traffic fatalities are Vehicle Miles Traveled and Vehicles Per Capita. It’s not just about making trips safer. Cities also need to be serious about growing the non-auto trips, which are, by their very nature, safer.

London's new Vision Zero plan is the best I’ve seen in terms of this. They're saying, "Yes, we want to make current driving trips safer. But if we’re going to get to zero deaths, we need to be reducing the number of car trips also. That means we need to be growing other kinds of trips." So you need to have carrots and sticks. Examples of carrots include building out a great, interconnected bike system network and complete, safe walking conditions. Then there are sticks, including things such as:

congestion pricing and, smart parking prices.

I know it's very early. And it's sort of hard to tell. Do you think Vision Zero is working?

Shahum: It is early. The longest-running two Vision Zero cities in the U.S. are 4.5 years in. I would say it’s very encouraging that these cities, New York and San Francisco, are seeing notable improvements, [though] the rest of the country has trended in the opposite direction, with more traffic deaths.

Veronica Vanterpool: In New York City there has been a significant reduction in traffic fatalities, they've decreased 28 percent. And there's been a 45 percent decrease in pedestrian fatalities.

Shahum: We've looked at the numbers for the first half of 2018 and it’s still trending down in both cities so that's encouraging. Those two cities that have invested the most time and energy and political will into this different approach [Vision Zero] are seeing results.

What about smaller cities with fewer resources? I live in Cleveland. Do you think smaller cities with less experience on these issues can succeed too?

Shahum: It’s all scalable. For a much bigger city, it’s going to take more resources. For a Cleveland or a Durham or we have 100,000-person towns we're working with in California that are committed to Vision Zero, you can be doing the same or very similar strategies, but they can be smaller scale.

In some of these smaller cities, they have this one road or two roads that are problematic, which are state highways and often big arterials. If they just fix that one or two streets, they would be light years ahead in terms of safety. It would be dramatic improvement.

Vanterpool: The goal of achieving zero fatalities, it isn’t just achievable through funding. There are policy changes that are needed. In New York City, we lowered the speed limit.

Funding is necessary because we want to make engineering changes to our roads. But policy change is also needed.

A lot of communities don’t realize how fungible a lot of federal and state transportation [funding is] as well. How they traditionally used those funds are for road improvements. Most cities have not taken advantage of the possibility of using the funds to add bike or pedestrian infrastructure. Once they do, they start to see opportunities within their existing budgets. This is how communities across the U.S have made these changes.

Sharing those examples is what the Vision Zero Network has done. Communities can learn from one another.