Transit should be a great social equalizer. Owning, fueling, maintaining, and insuring a car is expensive. Transit fares are not. Buses and trains should provide good access to jobs, education, and all the stuff of city life for people who can't afford the costs of cars.

In many cities, however, transit's potential to advance economic fairness is held in check because resources are distributed inequitably. The racial discrimination of redlining is still etched into cities in the form of segregation, household wealth disparities, and public service provision. Unless policy makers intentionally set out to use transit as a tool of social equity, it can just as easily exacerbate longstanding racial and economic disparities.

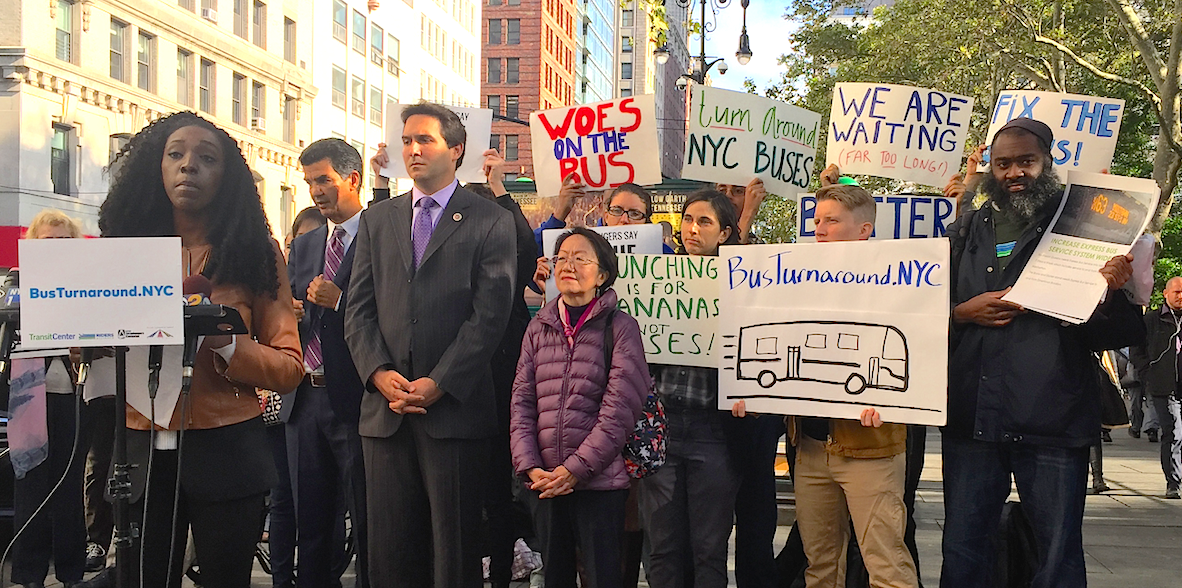

In a new report, TransitCenter lays out six principles for transit agencies to be a force for social inclusion [PDF]. Here's a summary of the recommendations.

1. Prioritize transit service for the people who need it most

When transit agencies cater to well-to-do suburbs at the expense of poorer city neighborhoods, it's a fundamentally unfair misallocation of resources. And it's very common.

Commuter rail investments like the Long Island Railroad's $12 billion East Side Access project shift resources away from high-ridership bus and train service to relatively low-ridership peak-hour rail service between office districts and affluent suburbs.

The particulars will vary according to the local context, and not every suburban belt is wealthier than the city core. But in many regions, suburban interests are overrepresented in transit agency leadership, skewing policy to favor well-off commuters from bedroom communities.

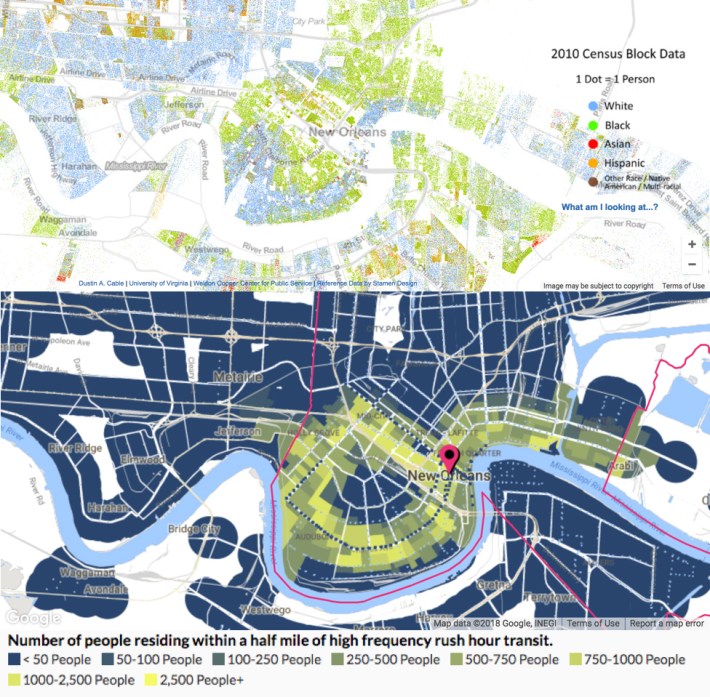

Decisions about major capital investment may also be dictated by property owners or other narrow constituencies whose interests don't align with providing good transit to people who need it. In New Orleans, for instance, the RTA has prioritized expensive streetcar routes in central, tourist-heavy districts at the expense of bus routes that serve residential neighborhoods, resulting in clear racial disparities.

"More than 40 percent of white residents in New Orleans have access to frequent transit at rush hour or better, while only 20 percent of black residents do," TransitCenter reports.

One agency that seems to be getting it right is San Francisco's Muni, which has set out to improve transit access to jobs, health care, and food for neighborhoods with a large share of low-income residents or people of color.

2. Fair revenue, fair fares

Transit agencies also need to ensure fare structures don't penalize poor people. TransitCenter recommends funding transit budgets with progressive sources of revenue to the extent possible. Property taxes, for example, are fairer than sales taxes.

For transit agencies that do rely on regressive revenue sources like sales tax, it's all the more important to ensure that service works well for low-income communities.

Some American transit agencies are taking the further step of restructuring fares to give lower-income riders a discount. Seattle's King County Metro, for example, runs a program called ORCA LIFT that offers people earning less than 200 percent of the federal poverty threshold a single-ride fare of $1.50, 40 percent less than the standard $2.50. Portland's TriMet is launching a similar program this summer.

Inclusive Transit - the videos! #1 ORCA LIFT fare program @SoundTransit @kcmetrobus pic.twitter.com/pbGdHxBicD

— TransitCenter (@TransitCenter) July 17, 2018

3. Plan and operate inclusively

Holding public meetings for the sake of checking off the "public engagement" box is not enough. To reach people who've been historically marginalized and may feel skeptical of the process, TransitCenter recommends that agencies team up with existing civic and neighborhood organizations to host meetings.

Some agencies have gotten more creative. The Maryland Transit Administration ran an "Info Bus" where staff could meet with riders and explain the redesigned bus system, BaltimoreLink. The Boston Transportation Department hosted a mobile "Ideas on the Street" workshop in 31 neighborhoods to gather feedback for its long-range transportation plan.

Sincere public engagement not only incorporates local knowledge to improve transit initiatives by tapping into hyper-local knowledge, TransitCenter says, it also helps increase public support for those improvements.

Transit agencies also need to be inclusive in recruitment and hiring. A 2007 review published by the Transportation Research Board found a dearth of women and minorities in transit leadership positions. TransitCenter recommends implementing racial diversity as a hiring criterion, especially for executive roles.

4. Plan for housing affordability

Transit agencies don't control most of the land within walking distance of stops and stations, but they can still use their influence to prevent transit improvements from increasing displacement pressures on vulnerable communities.

TransitCenter recommends transit agencies identify where there's a displacement risk -- usually places that were historically redlined. Then, when planning a project, transit agencies should advocate for greater density, lower parking requirements, and below-market rate housing in nearby development.

Transit agencies should also resist the tendency to favor large rail-oriented capital projects -- which can cause more upward pressure on property values -- over bus service improvements.

5. Support construction jobs in low-income communities

When transit agencies are planning big construction projects, they should hire from local neighborhoods and give preference in contracting to minority- and women-owned businesses.

6. Decriminalize fare evasion

Heavy-handed enforcement of fare evasion can impose excessive punishment on riders.

A handful of localities and transit agencies have decriminalized fare evasion, including San Francisco and Cleveland. Decriminalization doesn't mean that fare evasion is allowed, just that it is treated as a civil offense where the penalty is a fine, not a criminal charge.

TransitCenter recommends using transit agency staff rather than police to conduct routine fare enforcement. Having armed police officers on transit can intimidate riders and escalate into dangerous situations. TransitCenter also recommends tracking enforcement data by race and income to guard against bias.