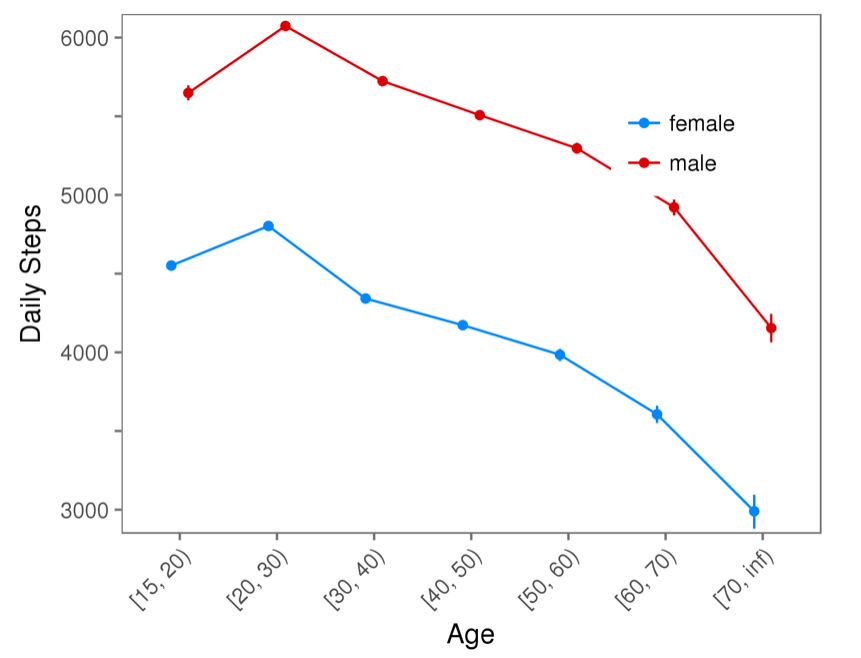

A recent Stanford study examined walking rates around the globe, finding that in a diverse range of countries, girls and women walk less than boys and men.

What explains the disparity? On International Women's Day, Tiffany Lam explores the subject at the Safe Routes to School National Partnership.

Planning professionals tend to focus overwhelmingly on infrastructure issues, she writes. While infrastructure matters a great deal, Lam says not enough emphasis has been placed on other types of barriers facing women and girls:

Women and girls have to account for threats and realities of gender-based violence in public—on public transportation, in schools, in workplaces, in parks, on streets -- and feel less inclined to walk in certain areas at certain times. As such, improving the safety of women and girls in public space will improve public health, too. UN Women has recognized the link between gender-based harassment and violence and female mobility in public space: Recently it launched a Safe Cities and Safe Public Spaces flagship program to prioritize safe streets for women and girls. This program acknowledges that while violence in the private sphere is now largely recognized as a human rights violation, sexual harassment and violence against women and girls in public spaces remains a pressing problem that is mostly unaddressed by lawmakers and policymakers.

Transportation planners predominantly think about safety in terms of safety from road traffic danger, which results in infrastructure-related interventions. While that is certainly important, safety is broader than that and includes safety from crime, racial profiling, and gender-based harassment and violence. A growing body of research focuses on the complex role of safety in active commuting for men and women, boys and girls. People’s perceptions of safety largely determine how, where, and when they get places. Many parents base their decisions about whether their children are allowed to walk or bike to school on how safe they think it is. Without a more holistic view of safety, we simply cannot reduce activity inequality, the gender step gap, and their negative public health outcomes.

Planner Katie Matchett has pointed out that transportation metrics focuses overwhelmingly on commute trips, which tend to be skewed toward men. Trips made by women tend to be shorter, and in many ways, ideal for walking. Planners may need to consider how design elements like street lighting and stroller access can help make cities more walkable for women.

Beyond physical infrastructure, groups like Hollaback! have been drawing attention to the problem of street harassment. But on transit, sexual harassment remains rampant, and there has been little institutional response in the United States. Internationally, some cities, like Guangzhou, China, have women-only cars on subways that are supposed to provide a refuge, though the policy has not been enforced.

One country with almost no walking gender gap is Sweden, reports the Guardian. The country uses a process called "gender-balanced budgeting" to analyze public spending. Among other things, the process led to changes in snow plowing: Local roads and sidewalks, which tend to be used more by women, now get priority over major roads. That change cost no additional money but resulted in big savings for society in the form of reduced injuries, the Swedish government reports.

A similar strategy has been employed to make transit safer for women. The city of Kalmar, Sweden, offers "night-stops" -- women can request a special stop at or very near their destination if they don't feel safe walking. When a night stop is requested, the bus driver doesn't allow anyone else to exit with the female passenger, for her safety. The concept has since been adopted in other places, including Toronto.