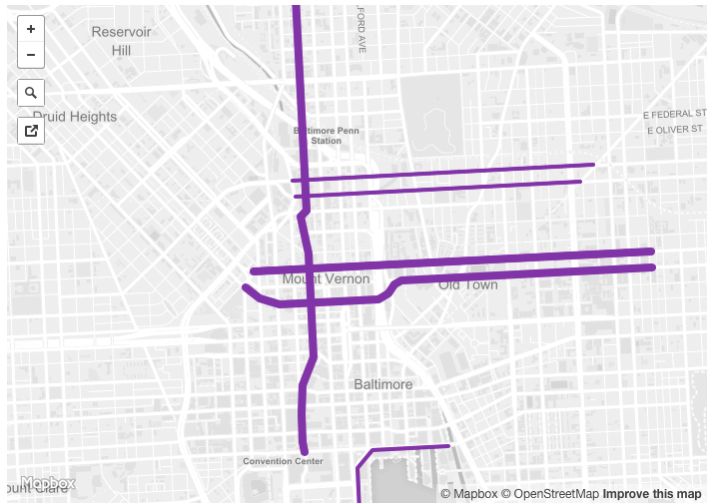

Baltimore was supposed to have a 10-mile downtown bike lane network by now: Six lanes of protected bike lanes and four miles of unprotected lanes. The $2.8 million plan was developed after extensive public feedback.

Instead, as of today, Baltimore has completed just 2.5 miles of bike lanes. The project is almost 100 percent over budget, and the bike network city residents were promised is not coming anytime soon.

This week, city officials decided to delay work by nearly another year, supposedly due to concerns about fire safety. The Baltimore Fire Department says its vehicles need 20 feet of street width to meet international fire code, which the city has adopted wholesale without modification to reflect local conditions. That conflicts with the bike lane designs -- and it also conflicts with many other typical Baltimore streets that just happen to not be very wide.

This story isn't just about inflexible bureaucracy run amok. It's about how car owners disingenuously steered the bureaucracy to block the conversion of on-street motor vehicle storage into bike infrastructure.

The 20-foot clearance issue was first raised by a group of residents who opposed a bike lane because it replaced parking. By presenting their campaign under the veneer of "fire safety" they've been able to deny progress on real street safety improvements.

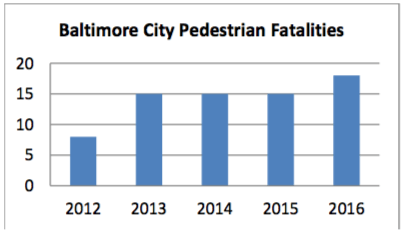

The bike lanes would not only make cycling safer, they've been shown to make walking and driving safer too, by reducing the prevalence of lethal speeding. Baltimore streets could use that type of engineering: Traffic fatalities are on the rise, with 53 people losing their lives in 2016, nearly double the rate in 2012. Among the victims were 18 pedestrians, up from eight in 2012 [PDF].

"They’re holding this up as a life safety issue," said Liz Cornish, executive director of the local advocacy organization Bikemore. "Meanwhile we’re ignoring the more pressing life safety issue — that’s people getting killed when they walk or bike in Baltimore city."

It's not uncommon for urban street redesigns to provoke objections from local fire departments about narrowing the right-of-way for their large vehicles. But most of the streets in Baltimore already don't meet the 20-foot standard, said Cornish, and it's never been an obstacle before.

Baltimore was one of 10 cities selected last year to receive support from People for Bikes to achieve dramatic increases in cycling. Many other cities applied for that grant funding. The fact that the clearance standard is being cited now suggests the city's real motivation isn't public safety -- it's mollifying the bike lane opponents upset about a few on-street parking spaces, without admitting it.

"You’ve been fighting fires on these narrow city streets," said Cornish. "This idea that all of a sudden it’s a problem is ludicrous."