Bus ridership is declining in almost every U.S. city. Some reasons are fairly obvious: Lower gas prices combined with higher transit fares and service cuts make transit less appealing. But observers aren't satisfied by those explanations alone.

Transit maven Jarrett Walker put out a call for academics to look into it. Laura Bliss at CityLab interviewed a barrage of experts searching for clues.

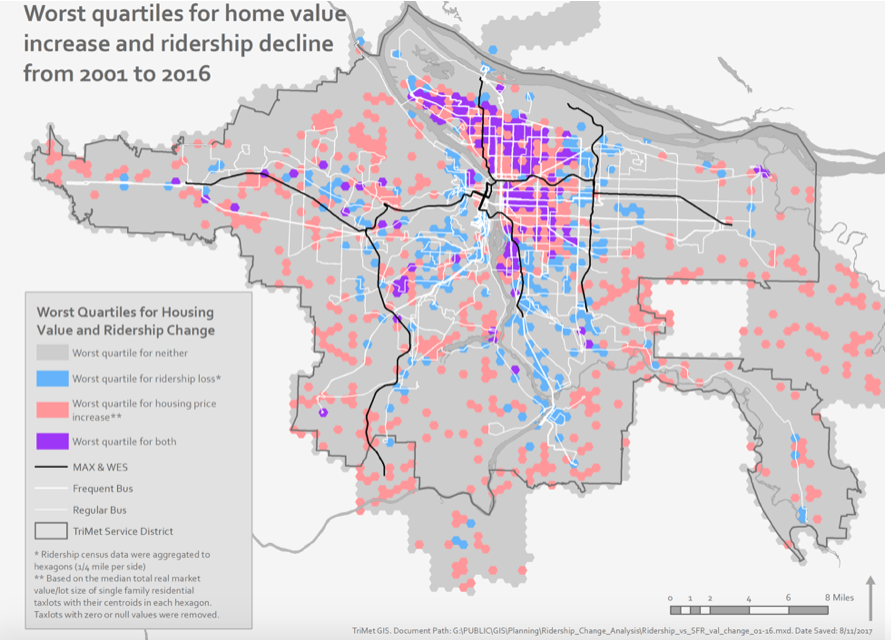

In Portland, one factor seems to be rising housing costs, with higher-income residents displacing lower-income residents in neighborhoods that traditionally have had robust transit ridership, according to an analysis by Tom Mills and Madeline Steele at Tri-Met, the regional transit agency.

In surveys, many people told Tri-Met that they ride transit less because of a change of home or work address. This led Mills and Steele to take a closer look at the interplay of ridership changes and the housing market. Writing at TransitCenter, they describe the findings:

We found substantial overlap between areas where real market home value increased and transit ridership decreased the most. These areas are concentrated in the same traditionally low-income, inner eastside neighborhoods that have experienced significant economic displacement. Correspondingly, transit ridership grew in areas that saw minimal increases in real market home values. These areas tended to be in the first ring suburbs where many low to moderate-income earners relocated after leaving the inner city.

These economic and demographic dynamics put our most loyal transit riders farther away from our best transit service, and strengthen the market for travel modes that are favored by high-income earning residents who may only use transit to commute. This may result in more walking and biking, but it also likely means more high-income people in and near our congested core are driving or using Uber or Lyft, at least during off-peak hours. At the same time, low-income earners are increasingly concentrated in suburban developments with a dispersed street network, low population densities, single-use land development and a lack of pedestrian infrastructure, all factors that discourage bus ridership.

Having a stronger menu of transportation options is good for TriMet riders and for the region, but we face a challenge as demand for transit shrinks in the most transit-supportive areas with the best transit service levels and demand grows in areas with lower-quality service. We would love to know if this phenomenon is occurring in other metro areas. This remains one of many factors driving transit ridership change, but it is also among the clearest and most challenging to navigate.

Portland's experience is not unique. In Atlanta, for instance, the suburbanization of poverty means more lower-income residents who lack cars have to navigate dangerous streets and poor transit service.

For transit agencies, any effective response requires coordination with the cities they serve. Mills and Steele say Tri-Met is working to win back riders by expanding suburban service, setting up a discount fare program for low-income riders, and teaming up with local governments throughout the region to prioritize bus service and pedestrian safety.