It wasn't that long ago that demolishing black neighborhoods to make way for highways was official U.S. government policy. In fact, though most cities now recognize what a horrible mistake that was, we can't even close the chapter on that era just yet.

Last week, public officials in Shreveport, Louisiana -- including Mayor Ollie Tyler -- voted to proceed with a 3.5-mile connector highway that will slice right through Allendale, a predominantly black, lower-income neighborhood that abuts downtown.

Economic development consultants with the firm Taimerica Management Company produced a report last year claiming the fate of the local economy is tied up in building this $700 million freeway link between I-20 and I-49. Urged on by the local chamber of commerce and transportation consultants at Providence Engineering, these arguments were enough to sway Tyler and other members of the regional planning agency to support the highway.

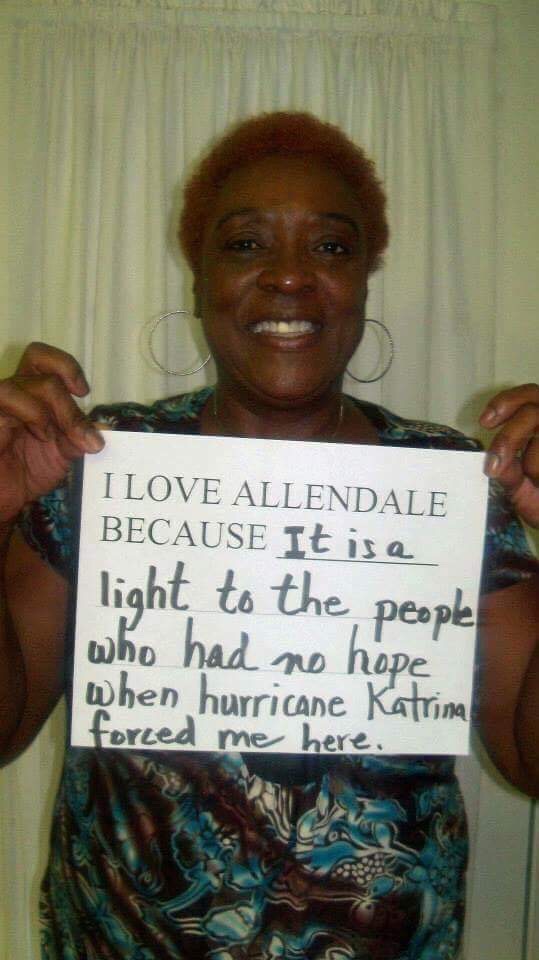

The vote was met with loud protests from Allendale residents who oppose the project. One of them is Dorothy Wiley, president of the neighborhood group Allendale Strong.

Wiley has lived in the neighborhood since 2006, when she evacuated New Orleans following Hurricane Katrina. Her house isn't directly in the path of the highway, but that's little consolation.

"I don’t want to live under or by a freeway," she told Streetsblog. "For me, no freeway should be coming through any community."

Despite having lost a large part of its population over the last few decades, Allendale had been planning for a 40-acre park, a botanical garden, and 150 units of new housing three years ago, the Shreveport Times reported.

Wiley and her group have been mobilizing against the highway for years.

But city leaders, including Tyler and Council Member Willie Bradford, who represents the neighborhood, sided against them. Tyler and other members of the metropolitan planning organization for northwest Louisiana voted unanimously last week for a highway alignment that cuts through the neighborhood. They said the economic arguments for the project convinced them.

Over at Strong Towns, Charles Marohn refuted the economic development argument earlier this year. He points out that even the consultants hired to boost the $700 million highway spur expect almost no one to use it.

The Taimerica report -- which is basically a public relations document for the project -- projects the number of daily trips on the highway will number about 3,600. That's far lower than the traffic volume on many three- or four-lane urban surface streets, which get tens of thousands of daily car trips.

And yet Taimerica predicted this 3.5-mile highway segment will somehow produce 30,000 new jobs and $800 million in economic "benefits." (Shreveport only has about 200,000 residents.)

Wiley said she and her group will continue to fight a project that maintains the racist legacy of American urban highway construction. "They always want to find a black community to bring it through," she said. "These people been living there 50, 60 years, they don’t want to be uprooted."

A final vote on the project is expected at the end of next year, the Shreveport Times reports.