America is aging -- by 2030, 20 percent of the population will be 65 or older, up from 14 percent today. It's a demographic shift with big implications for urban transportation. Older Americans drive less but still want to get out and experience their cities.

In a new briefing paper based on extensive surveys, TransitCenter shares recommendations to better serve America's aging population [PDF]. Here are five takeaways for transit agencies and cities to help people age in place by providing transit service that meets their needs.

The basics of good service still matter

First, it's important to understand that some things don't change as people get older. Access to frequent, reliable service is the top priority for transit riders 65 and older, according to a TransitCenter survey, the same as it is for younger riders. Transit agencies have to start with the basics of good service.

Comfortable waiting areas and vehicles

What older riders do prioritize more than younger riders is comfortable waiting environments and vehicles. In a 2016 TransitCenter survey, seniors said they wanted bus stop shelters nearly as much as more frequent service. Shorter walks to stops and stations, fewer stairs to climb, and smoother rides will increase seniors' comfort using transit.

Walkability and accessibility

Walking is the most common way for all riders, including seniors, to access transit. The less strenuous the walk to transit, the more seniors will ride. Transit agencies have to coordinate with cities to create good walking environments around transit, and to concentrate development along transit corridors to keep service within easy walking distance of where people go.

TransitCenter says transit agencies should place special focus on meeting the standards in the 1990 Americans with Disabilities Act. Some agencies remain far behind on accessibility. In New York, for instance, 362 of 472 subway stations do not meet ADA requirements.

Make paratransit efficient and convenient

A higher proportion of riders older than 65 rely on paratransit, point-to-point services for people with physical impairments. But paratransit tends to be expensive to administer and still inconvenient for riders.

Increasing reliance on paratransit could strain transit agencies' already tight budgets. The average door-to-door paratransit trip costs $29.30 to provide, compared to $8.15 for a fixed-route trip on a bus or train. Even so, the waits for passengers can be extensive, requiring 24-hour advance booking.

But there's a lot agencies can do to make paratransit services more efficient and rider-friendly. TransitCenter recommends linking paratransit to fixed route service where possible, for example. A paratransit van might take a rider from his or her home to a nearby train station instead of the final destination, provided that station is accessible. This kind of coordination can cut costs in half compared full point-to-point service. Houston, Pittsburgh, and Vancouver have all moved toward this model.

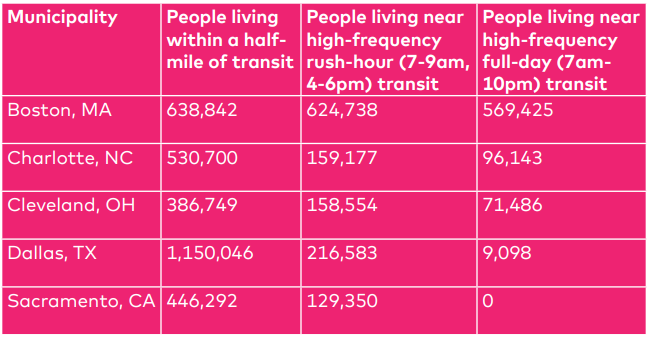

Increase nighttime and weekend service

People ages 65 and up are less likely than younger people to use transit for commuting, naturally. So service that runs frequently all day, not just during rush hours, is especially important to them. Of course, TransitCenter notes, expanding frequent service to midday, nights, and weekends will boost ridership not only among older people, but the general population as well.