Maryland's Republican governor, Larry Hogan, enjoys a moderate image and one of the two highest approval rates of any governor. At 71 percent, he is tied with fellow moderate Republican Charlie Baker of Massachusetts. Like Baker, Hogan won in many liberal areas, cutting into Democratic margins in the DC suburbs, and he cultivates a fiscally prudent persona.

Last month, I covered Baker's flawed transit agenda. And like Baker, Hogan's transit decisions belie his reputation as an efficiency-focused technocrat.

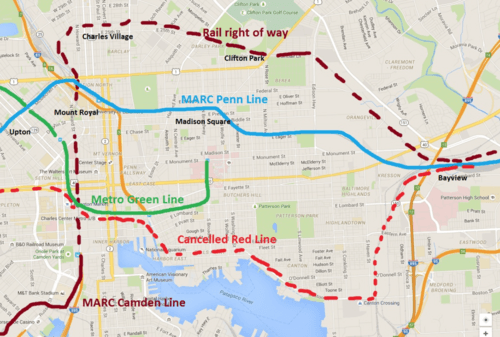

When Hogan was elected in 2014, there were two major rail projects in the state about to begin construction: the Red Line, an east-west light rail subway in Baltimore serving predominantly black low-income neighborhoods on the West Side and East Side; and the Purple Line, a light rail line in the DC suburbs, serving both black middle-class Prince George's County and white, wealthy Montgomery County, connecting suburban stations of the Washington Metro as a circumferential line.

The two projects had similar projected costs per rider. But Hogan canceled the Red Line on cost grounds, while continuing with the Purple Line.

The 14-mile Red Line was projected to open in 2022 and draw 54,000 weekday riders by 2030. The cost estimate at the time of cancellation was $2.9 billion, or $54,000 per daily rider. Two-thirds of the line's length would be at-grade, with four miles of tunnel, explaining the seemingly low cost per mile of $200 million.

Unlike older rail lines in Baltimore, the Metro Subway and the Light Rail, the Red Line was supposed to focus on service within the city, barely extending into the suburbs. This orientation around the urban core boosts the Red Line's ridership projections of nearly 4,000 per mile -- better than the Subway's 2,500 and the Light Rail's 1,000.

The 16-mile Purple Line has a projected weekday ridership of 65,000. The cost is similar to that of the Red Line, but it is hard to give a comparable figure, since the contract of the public-private partnership leaves its costs opaque. But My understanding is that construction will cost around $3.3 billion, a figure that leads to a cost per rider close to that of the Red Line.

The racial discrimination implicit in canceling the Red Line but not the Purple Line prompted a Title VI civil rights lawsuit, and a federal investigation under the Obama administration. When pressed on the matter at a hearing, the state's transportation secretary, Pete Rahn, engaged in obfuscation, as can be seen in this hearing (starting at the 48 minute mark).

Rahn questioned the cost estimates of the Red Line, saying that the $1 billion estimate for tunneling was a dubiously low figure by the standards of the Baltimore and Potomac Tunnel replacement project, which he cited as $1.68 billion for 1.9 miles. In reality, the B&P project has far greater scope, which is why it got so expensive: The entire four-track project will cost up to $4 billion.

The B&P project is so expensive because the tunnels are sized to be used both by high-speed trains, leading to much wider tunnel diameter than for the Red Line, and by diesel-powered freight trains, leading to expensive ventilation that is not required for subway tunnels used exclusively by electric trains. Samuel Jordan, the president of the Baltimore Transit Equity Coalition, noted these differences between the B&P replacement and the Red Line in pushing back against Rahn's inflated cost estimates.

But a serious Title VI investigation seems unlikely at this point. Rahn himself mocked supporters of transit equity by saying that the federal government's letter warning of a Title VI case came on January 19, a day before Trump's inauguration, and that the Trump administration would not investigate Maryland for possible racial bias, but instead might investigate the U.S. DOT official who sent the warning letter for not going through proper channels.

There is a long history of transportation policy as a tool of the state government to isolate Baltimore's majority-black population. In Places Journal, Alex MacGillis writes about the legacy of highway-fueled white flight in Baltimore, and the sheer resentment suburban residents feel toward transit serving the city ("loot train").

Hogan's war on Baltimore is not restricted to transportation. He canceled a mixed-use transit-oriented development project in the city, called State Center. He has balanced the state's budget by cutting funds for Baltimore city schools, for which he was excoriated in Baltimore Sun editorials. Individual cuts are often defensible on grounds of efficiency, but when placed together, the pattern is incriminating.

With transportation, the pattern is not just that Hogan canceled the Red Line. It's that he canceled the Red Line but not the Purple Line. He even listed the Purple Line as an infrastructure priority to be placed on Trump's wishlist, even though it was already funded. What's troubling is that these decisions seem to be strengthening Hogan's political hand even in "blue" Maryland.

Hogan's high approval rating suggests that his pattern of discrimination is not unpopular in middle-class white Maryland. Nor were his promises to redirect money to roads in the 2014 gubernatorial campaign unpopular in the Baltimore suburbs. Statewide, he won by 5 percentage points, but in Baltimore County, which comprises most of the Baltimore suburbs (Baltimore City is independent of the county), he won by 21 points.

Baltimore County rarely leans this far Republican: In the 2012 and 2016 presidential elections voters there sided with Obama and Clinton by 17 points (the state as a whole voted for both by 26 points).

So Hogan got a special boost in the county, relative to the state. His brand of anti-urban racism is popular in the suburbs founded by people who fled the city and its burgeoning black population in the postwar years.