Michael Andersen blogs for The Green Lane Project, a PeopleForBikes program that helps U.S. cities build better bike lanes to create low-stress streets.

The bible of U.S. bikeway engineering, last revised just before the modern American protected bike lane explosion, will almost certainly include protected lanes in its next update.

That's the implication of a project description released last month from the American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials.

AASHTO's current bikeway guide doesn't spell out standards for protected bike lanes. Its updated edition is on track to be released in 2018 at the soonest. A long wait? Yes, but that would still shave seven years off the previous 13-year update cycle.

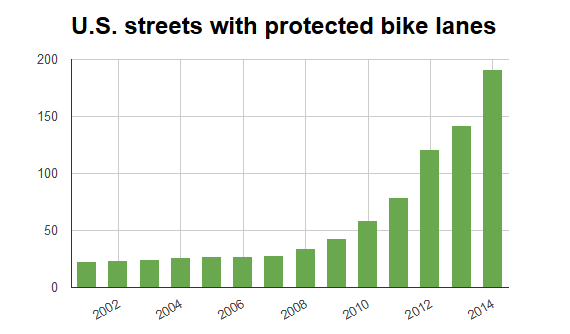

"Back in 2009, we maybe had a few miles of separated bike lanes in this country," said Jennifer Toole, founder of Toole Design Group and the lead contractor who wrote AASHTO's current bike guide. "It was written right on the cusp of those new changes. Now we have all kinds of experience with this stuff. And data -- we've got data for the first time."

AASHTO's richly detailed and researched guides are the main resource for most U.S. transportation engineers. Some civil engineers simply will not build anything that lacks AASHTO-approved design guidance.

However, dozens of cities in most U.S. states have now begun building protected lanes with the help of other publications.

While drafting the current AASHTO guide in 2009, Toole's team actually included a chapter including protected bike lanes, based on designs and data from The Netherlands and elsewhere. But AASHTO's review committee agreed that there wasn't enough data on how Americans in particular use such designs, so the chapter wasn't included in AASHTO's final publication.

Since then, other organizations have stepped in to fill the vacuum. In 2011, the National Association of City Transportation Officials released its first Urban Bikeway Design Guide, a less prescriptively detailed manual. In 2013, the Institute of Transportation Engineers followed with Separated Bikeways.

In 2014, both of those manuals got formal endorsements from the U.S. Department of Transportation, which in a memo listed them alongside AASHTO's guide as sources of useful information.

California, Colorado, Delaware, Massachusetts, Minnesota, Tennessee, Utah, Washington, and many U.S. cities have since endorsed NACTO's Urban Street Design Guide. The Federal Highway Administration is also preparing to release on its own guide about protected bike lanes, similar to NACTO's in level of detail.

In 2014, Massachusetts even hired Toole's company to write a state-specific engineering manual about protected bike lanes. It's due for release this spring.

Even with acceleration, a slow update cycle

Those developments seem to have accelerated AASHTO's update cycle. The organization's new project description observed:

Many state DOTs would like to see additional research on innovative bicycle treatments so that they can make informed decisions at the project level, including accommodation of different modes of traffic using the road. The Guide is referred to in the FHWA memorandum as the "primary national resource for planning, designing, and operating bicycle facilities" and so there is a need to keep it accurate and current.

Bill Rogers, who is managing the process of contracting out the bikeway guide for the Transportation Research Board of the National Academies, said Monday that a contractor will be chosen on April 2, and that work would begin in May and continue for 27 months.

After that, he said, AASHTO's committees will need to approve and publish the guide.

"The state of the art is moving so fast in the field that it will be out of date the moment it is published," said Andy Clarke, president of the League of American Bicyclists, in an interview Tuesday. "That still raises the bar for 70 percent of the engineering work on our states and highways... Compared to what we were using in 1991, it's miles ahead."

Jamison Hutchins, bicycle and pedestrian coordinator for the city of Indianapolis, said Monday that AASHTO's action is "exciting."

"NACTO has been out in front, raised the bar and has demonstrated that professionals in the bike and pedestrian world will use more innovative resources if they are available," Hutchins wrote in an email. "Many of the proposed updates have been tested in cities around the country and have proven to be the best option. Having them validated in AASHTO adds another level of legitimacy and allows us to move even further."

You can follow The Green Lane Project on Twitter or Facebook or sign up for its weekly news digest about protected bike lanes.