High-occupancy vehicle lanes can help incentivize carpooling (and let solo drivers sit in punishing congestion). But too often, transportation agencies spend millions of dollars to widen the road to make carpool lanes, instead of simply designating existing lanes. To recoup some of the expense, the agencies also let drivers pay to use the new "high-occupancy/toll lane."

HOT lanes are often derided as "Lexus lanes." But they can benefit transit riders, too, if cities and transit agencies know how to use them.

Most don’t, though, so the good folks at the Center for Neighborhood Technology wrote a guide, published last week in the Journal of Public Transportation.

HOT lanes, at their best, offer a form of congestion pricing -- charging drivers a variable price to use a congested roadway depending on the time of day. And those tolls can help pay for more efficient transportation on that roadway.

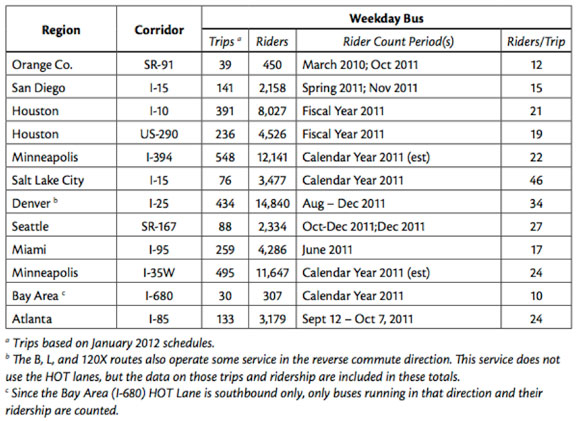

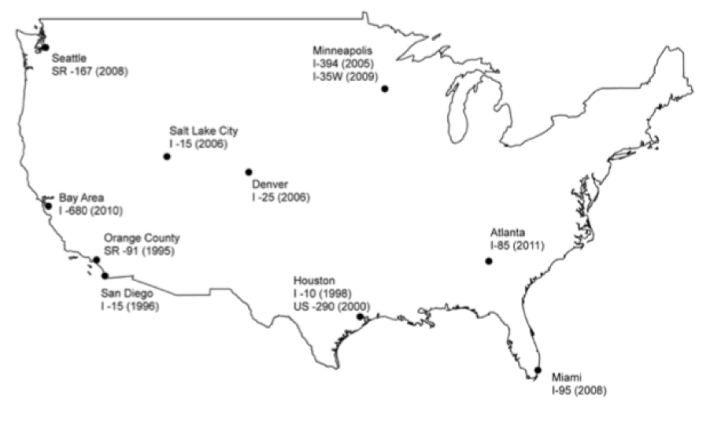

In 2012, there were 12 HOT lanes operating in the U.S.,which CNT’s Gregory Newmark examined for his report. The great majority are in the South and West. Most of them are on interstate highways. All of them have bus service.

In places where adding transit is politically difficult, HOT lanes can be a way to sneak in service improvements. "Miami, which had repeatedly failed to gain voter approval for increasing local transit funding, was able to use federal monies for the HOT lane project to purchase buses to operate three new express routes," Newmark writes. “Federal funding was similarly leveraged in Minneapolis and Atlanta. In San Diego, the HOT lane project was designed, in part, to fund new express bus service along the corridor.”

Newmark says expanding roads to make HOT lanes leads to better transit performance than turning existing HOV lanes into HOT lanes, which risks congestion in the lanes. But he doesn’t investigate the option of turning regular traffic lanes into HOT lanes. And some transit agencies have put in safeguards to prevent buses from getting slowed down: When Denver converted an HOV lane to HOT, the toll operator made an agreement with the local transit agency that any degradation in bus travel times would trigger a review to determine if a toll rate increase is necessary.

Denver also struck a smart deal to ward off the possibility that the conversion to HOT lanes would encourage people to make the “socially-undesirable mode shift” from transit to driving once they didn’t have to worry about congestion. (While the limited research that’s been done in this area doesn’t show a major shift from transit to driving with the installation of HOT lanes, the possibility is certainly there.) Denver officials agreed that peak-period tolls on I-25 would be legally bound to stay at or above the express bus fare along the corridor “so that driving never has an out-of-pocket cost advantage,” writes Newmark.

Minneapolis has the distinction of serving the most transit riders with its HOT lanes. Dozens of bus routes run on the HOT lanes on I-394 and I-35W, with each road serving about 12,000 transit trips daily. Only Denver’s I-25, which runs fewer buses but averages more riders per bus, has higher daily transit ridership -- 14,840 trips.

Orange County and the Bay Area have the worst-performing HOT lanes in terms of transit ridership: They’re the only ones that carry fewer than 2,000 passengers per day, and they carry way fewer. Newmark speculates that the low ridership is primarily a product of land use: The HOT lanes serve secondary job centers with dispersed employment locations.

All HOT lanes should direct some revenue to transit on the corridor, but some don't -- even when transit agencies are the official operators of HOT lanes. That’s the case in Orange County. Most at least allow "excess" or net revenues to be transferred to transit -- whatever is left over after the expense of maintaining and operating the lanes. Some places even require it. In Miami, though, the cost of operating transit is considered one of the essential expenses of the HOT lane, so some toll revenue is guaranteed. (Which is good, because although Miami’s legal structure allows for excess to be directed toward transit as well, officials have chosen not to do so.)

Of course, toll operators across the country have learned the hard way that their revenue expectations are often inflated. Of the 12 HOT lanes studied in 2012, four operated in the red that year. So transit agencies shouldn’t count on HOT lane excess profit as a revenue source, either.

Design problems can make HOT lanes difficult for transit, too. For instance, HOT lanes need to be designed with transit agency input in order to make entering and exiting as easy as possible for buses. “Many bus drivers along Seattle’s SR-167 forgo using the HOT lane, as quickly crossing from the right-side highway entrance ramp to the left-side HOT lane entry is a difficult maneuver,” Newmark wrote. “Similarly, bus drivers along Minneapolis’s I-394 found entry difficult at one particular access point and complained that motorists, who were now enjoying the smoother flows of the limited-entry HOT lane, were less likely to yield to buses at the access points.”