Hartford, Connecticut, has one of the highest poverty rates in the country. The urban renaissance that has visited so many cities hasn’t arrived there. Housing is still cheaper in the city than in the suburbs, and although suburban poverty is growing alarmingly fast, it’s nowhere near the levels seen in the city.

There are multiple complex factors that have contributed to Hartford’s woes. But one of them, clearly, is the degree to which the city enabled car-centric infrastructure to proliferate.

As Payton reported last week, Hartford tripled its downtown parking capacity between 1960 and 2000 while squeezing everything else onto 13 percent less land. Avert your eyes if you have a weak stomach:

Norm Garrick, a lead researcher on two studies comparing Hartford’s parking policies with five other cities, says the amount of tax revenue Hartford forfeits by devoting so much downtown land to parking “amounts to a subsidy of more than $50 million per year.”

“To put this number in perspective,” he told UConn Today, “all the real estate downtown contributes just $75 million in municipal revenues each year.”

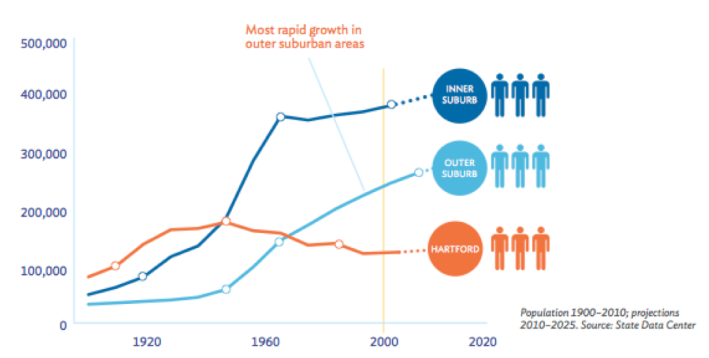

A new report from the Hartford Foundation for Public Giving shows how Hartford is now paying for the decision to facilitate car travel first and foremost. The population is still bleeding out of the city and into the suburbs, especially among whites. The population is also aging across the region, with the number of seniors expected to grow by 73,900 between 2010 and 2025, while the number of people under 55 is projected to shrink by 42,900.

The parking-and-highways approach to transportation policy has yielded the commute patterns you’d expect: job sprawl and lots of single-occupancy car trips. The region has an 81 percent drive-alone commuting rate -- higher than the national average of 76 percent and especially high for a metro area of its size. More stunning is the mismatch between jobs and housing: While 83 percent of jobs in Hartford are filled by commuters from outside the city, 65 percent of Hartford residents go outside the city to work. Among the reverse commuters, 75 percent earn less than $40,000 a year.

With recent grads and retirees alike flocking to walkable cities and exhibiting an increasing indifference toward driving, Hartford made a tragic miscalculation by building itself around cars, not people.