The above photo is downtown Denver in 1976.

Not pretty is it? But Denver doesn't look like that anymore. And that's no accident.

Even though that picture is what inspired Streetsblog's Parking Madness competition, Denver didn't even make it past the first round in our hunt for the worst parking crater in an American downtown.

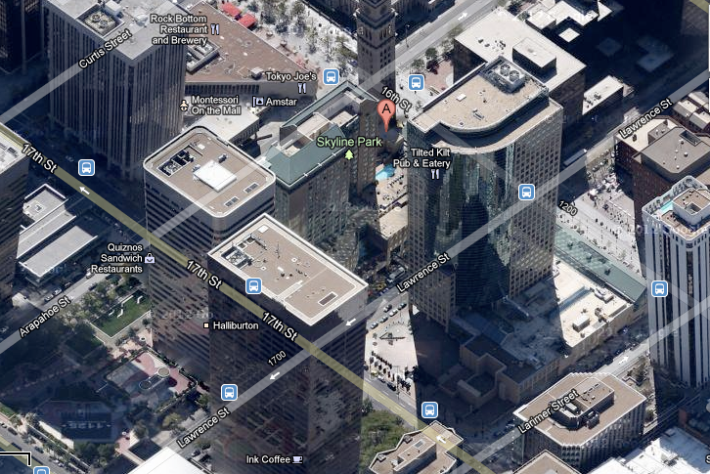

This is what this part of Denver looks like today:

In the 1990s, in response to the creeping cancer of surface parking, the Mile High City took action. The city changed its downtown zoning to eliminate surface parking as a use by right. So if you owned a building, you were welcome to tear it down, but you couldn't park cars on the lot. All existing parking lots were grandfathered in.

Many of the lots in the 1976 photo were created by urban renewal campaigns in the 1960s and 70s. "The urban renewal authority would just come in and bulldoze dozens of blocks as a slum clearance program," said Ken Schroeppel, of the blogs Denver Urbanism and Denver Infill.

But there were other forces at work as well. During the 70s and 80s, says Schroeppel, "[Downtown] Denver went through a big development boom." A lot of office towers were built, but the city code didn't require attendant parking. "You had this huge influx of downtown workers without the parking to accommodate them."

Some property owners saw an opportunity and demolished their buildings. On one hand, they were speculating, hoping a cleared site would catch the eye of a skyscraper developer. On the other hand, they could always collect revenue by using the site as surface parking in the interim.

That 1990s zoning change was the only official action Denver took to stop the spread of parking lots. But the city has held firm, keeping the number of surface parking levels at no greater than they were in the 90s. Even where developers were ignorant of the rule change, the city intervened to stop them from building parking lots.

Meanwhile, other city policies helped ensure many of those lots would be filled in by revenue-generating businesses.

For example, Schroeppel says there's broad agreement in the Denver metro area that all the major regional attractions -- stadiums, museums and the like -- should be centered downtown. Rather than offering big incentives to developers, Denver leaders believe in simply helping create an attractive environment for investment, with small-scale amenities like transit, historic preservation and streetscape projects.

Little by little, over the last few decades those surface parking lots are being redeveloped. Redevelopment is stronger in some areas than others, Schroeppel says, and there are still a few "concentrations" of parking, but the problem of parking deserts has been reduced dramatically.

That's good news for Tulsa, which ran away with our "Golden Crater" award for out-of-control downtown surface parking last month. Last week, the Tulsa World reported the city is moving ahead with a surface parking moratorium much like Denver's. Who knows, 20 years from now we may be holding up an "after" picture to match this current shot of Tulsa.