To hear some urbanists talk, you’d think the outer suburbs have been abandoned wholesale, lawn-mowers still running with no one to drive them, picket fences left open in the owners’ haste to beat it to the city.

A new Brookings report puts the re-urbanization of America in perspective. During the economic crisis, from 2007 to 2010, job sprawl receded ever so slightly. And not everywhere. Actually, in more than half of the 100 biggest metro areas, job sprawl actually increased -- it just increased less than it decreased in the other ones.

All in all, the economy shed jobs virtually everywhere between 2007 and 2010. So the rush to create new jobs in the outer reaches of suburbia halted, because there were no new jobs, period. As it happened, though, urban cores lost a slightly smaller share of their jobs than outer-ring areas.

Report author Elizabeth Kneebone has been tracking job sprawl trends for years, and she says that although there are still more jobs outside cities than in them, the recession has had a notable impact.

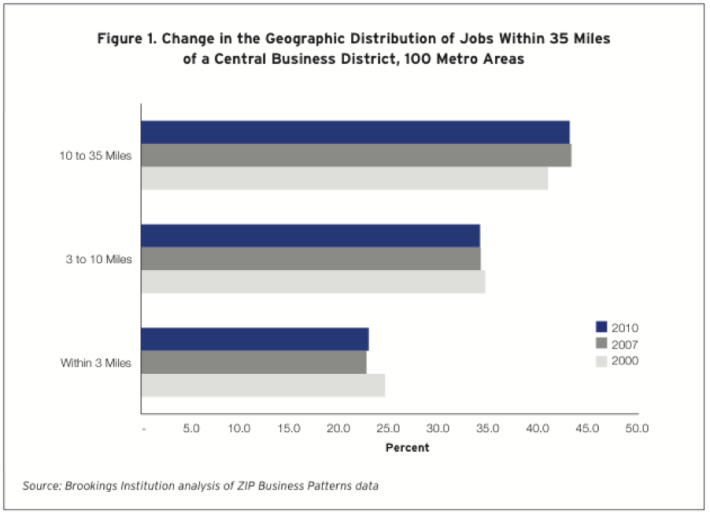

“After dropping two percentage points from 2000 to 2007, the share of metropolitan jobs within three miles of downtown stabilized from 2007 to 2010,” she wrote. “However, by 2010 nearly twice the share of jobs was located at least 10 miles away from downtown (43 percent) as within three miles of downtown (23 percent).”

So 43 percent of the jobs are more than 10 miles from downtown, and 45 percent of the job losses happened there.

You can forgive me for expecting bigger numbers. We hear so much about the growing preference for urban living, especially among young people at the beginning of their careers and seniors at the end of theirs. The exurbs are in steep decline; houses that once would have been a symbol of status in the outer suburbs are now occupied by Section 8 voucher holders. Chris Leinberger, also of Brookings (and many other places), has written about the increasing premium of commercial real estate in urban locations over suburban ones.

Kneebone's expertise in this area has led her to a more nuanced expectation. She says she wasn’t surprised by the modest nature of the decrease in job sprawl, especially since the data stop at 2010, and the changes I just mentioned have continued since then.

But the barely-perceptible contraction in the exurbs' job share is notable because it follows seven years at the beginning of the last decade of unchecked job movement to the outer fringes, when "the outer ring added employment at four times the rate of the middle ring, while the number of jobs located within three miles of a CBD actually fell.” These new numbers show that the juggernaut of outward growth has not only stopped its march, it has taken a step backward. And even this tiny step backward is, indeed, a monumental shift.

Much of the shift is attributable to changes in just three industries: construction, manufacturing, and retail. As we know, construction employment is in a deep freeze, thanks to the housing crisis and the tight lending environment. In the early part of the last decade, a lot of the construction was happening in greenfield areas far outside of town. That -- along with manufacturing, which has been in decline for decades, and a more modest reduction in retail jobs -- accounts for 60 percent of the job losses between 2007 and 2010, with half of those losses occurring at least 10 miles from downtown.

Washington, DC, is the shining star of this research – and I’m not just being biased here. DC was the only metro area to see both the total number and the share of jobs in the urban core grow during the 2000s. It’s not just our recession-proof, doom-boom economy – it’s the resurgence of our downtown.

The results are even more dramatic when you realize that Washington, DC, itself is the only Central Business District recognized by the research. Major job centers outside the city, like Alexandria or Rockville, for example, don’t count even as a secondary CBD because they don’t have at least one-third the employment totals of DC itself. (The same goes for New York City, none of whose satellite cities get credit as CBDs.) In contrast, the Allentown-Bethlehem-Easton metro area in Pennsylvania has three CBDs listed, since none of them dwarfs the others.

Among the surprising trends Kneebone found is this one: Areas with more jobs tend to have a smaller share of them in the urban core. I would have expected bigger metros to have more vibrant downtowns, but that doesn’t seem to be the case. Detroit, sadly, leads the way on this, with 77 percent of its jobs in the outer ring.

“On average, metro areas that contain fewer than 500,000 jobs have 30 percent of jobs in the urban core, outstripping the outer-ring job share by almost 6 percentage points,” Kneebone wrote. “In contrast, the 42 metro areas with more than 500,000 jobs (which are home to 78 percent of all jobs within 35 miles of a downtown in the 100 largest metro areas) locate an average of just 21 percent of jobs in the urban core, and more than 48 percent of jobs at least 10 miles from downtown.”

Also noteworthy is the finding that politically fragmented places – split into more jurisdictions – are more decentralized. Kneebone speculates that this is because communities compete against each other to attract jobs.

Will job sprawl pick up where it left off when the recovery gains steam? It certainly could, Kneebone says. And that would be a hot mess. “If the next period of economic expansion ushers in low-density, diffuse growth in metropolitan America, the negative consequences of decentralization will make it that much harder for metro areas to achieve sustainable and inclusive growth over the long term,” she writes.

Luckily, urban areas are wising up to the benefits of compact development and locating jobs near residences (and retail near both). Community leaders are beginning to understand the importance of being strategic and intentional about connecting jobs, housing, and transportation.

“There are a number of regions that are adopting strategies to encourage job location downtown and denser growth in the urban core,” Kneebone said in an interview, “just as there are places that are trying to pursue smarter suburban development.”

Not all decentralization is sprawl, she said. “But it takes intentional planning and policy decisions to make sure that as a region grows outward, it’s doing it in compact, smarter ways that make it easier to connect these suburban jobs to transit and to housing so that we avoid the challenges that come with more spread-out, diffuse development at the metropolitan fringe.”