How substantial are the benefits delivered by federal investment in bus rapid transit projects, and how can the feds help local governments build better bus improvements? A new report from the non-partisan Government Accountability Office [PDF] looks at the results of BRT projects that have been completed in 20 cities since 2005, when SAFETEA-LU expanded federal funding eligibility for such projects. The GAO found that almost all of the projects have proven successful as cost-effective upgrades to increase ridership, but it also identified a few ways that federal policy provides incentives for local governments to avoid building bus projects that meet the standards for high-quality BRT.

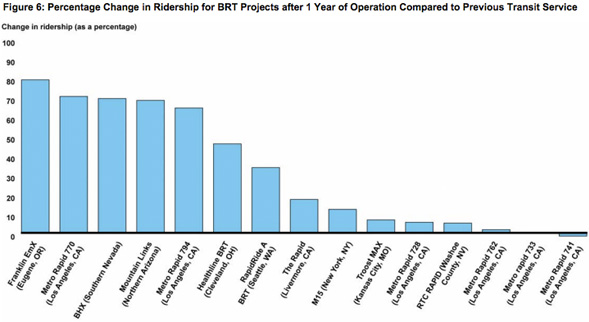

Ridership is up on 13 of the 15 routes that were completed in time to furnish data for the study. (On the other two routes -- both in Los Angeles -- local officials claim the BRT projects have still led to increased ridership on local bus routes.) In many cases, ridership increased by more than 30 percent in the first year, and five projects saw ridership jump between 60 and 80 percent. These are people who would not have taken transit if not coaxed aboard by these federally-funded improvements, including peak travel time savings ranging from 10 to 30 percent.

Still, few of these projects meet the standard for "true BRT" developed by the Institute for Transportation and Development Policy. Since bus rapid transit consists of a menu of possible improvements -- such as off-board fare collection, dedicated bus lanes, and platform-level boarding -- local governments often end up calling a project "BRT" when it's really just a smattering of different upgrades. And the GAO report bears this out, finding that all 20 routes took the menu of BRT features as mere suggestions, often incorporating just a few of them. Some of the more significant ones – with the most power to cut travel times and increase ridership – were also the most expensive, and therefore the least used.

Only three of the 20 bus routes run on a dedicated lane for at least 30 percent of their length. Two more run on a “semi-dedicated” lane at least 30 percent of the time. A dedicated lane can allow buses to speed past bumper-to-bumper traffic, but most of the routes the GAO studied operate primarily in mixed traffic on arterial streets. With capital costs averaging $50,000 to $100,000 per mile in mixed traffic -- compared to $2 to $10 million per mile for projects that have dedicated lanes – it’s understandable why so many communities have opted to keep it cheap. And in some cases, such as Kansas City, congestion is low enough that a dedicated lane would be an unnecessary expense.

Other BRT features -- like off-board fare collection, low-floor buses that speed boarding, and technological improvements like transit-priority signal timing – were more widely adopted. One of the GAO's interesting contributions is its explanation of why agencies opt for certain BRT upgrades but not others. Incentives to skimp on bus projects may actually be baked into federal funding formulas.

To qualify for a New Starts grant, the Federal Transit Administration requires BRT projects to meet the definition of a “fixed-guideway” for at least 50 percent of its length during peak hours. Or, to be a “Small Starts” project, it should be a corridor-based bus project that contains certain upgrades. Since the fixed-guideway requirement is often considered cost-prohibitive, the vast majority of cities – 28 out of 30 – got their federal funding through the Small and Very Small Starts programs.

But the way this funding is configured may end up pushing communities to scale down their ambitions, since funding from "Very Small Starts" is capped at $50 million per project. (The new transportation authorization, MAP-21, seeks to eliminate “BRT creep” -- the watering down of BRT projects into minor upgrades over standard bus service -- by requiring not just fixed-guideway but separated right-of-way for New Starts BRT projects.)

The relative economy of bus improvements compared to rail projects has given federal funding programs a huge bang for their buck – BRT represents 30 of the 55 New/Small/Very Small Starts grants since 2005 but accounts for less than 10 percent of committed funding. Those are great numbers for any local or federal official looking to stretch scarce transit dollars, but are they being stretched too far and turned into projects that are weaker than they should be?

The GAO writes:

The limited use of BRT’s more costly features might also partly reflect the relatively large role that the Small and Very Small Starts programs have played in funding recent BRT projects as compared to state and local funding sources. The funding these programs provide to smaller transit projects has allowed communities that otherwise may not have been as competitive in the New Starts process to obtain federal transit support. However, it is possible that limits on the total project cost create incentives for BRT project sponsors to omit more costly BRT features. In general, though, it appears that BRT project sponsors are using the Small and Very Small Starts programs to design and implement projects that address their communities’ current transit needs and align with the projects sponsors’ overall objectives.

Of course, it’s not just federal funding hurdles that weaken BRT plans. Sometimes drivers resist giving up a traffic lane to buses, as in Los Angeles, or businesses raise a stink over reduced parking, as in Eugene.

Officials are also sometimes content to put off until tomorrow what they could do today. Because BRT is based on a menu of separate improvements, project developers can leave space for possible future improvements instead of building the most complete possible BRT system from the get-go. In four of the five BRT locations the GAO traveled to, communities were planning to incorporate more features in the future. Still, that’s not necessarily a bad thing, since it allows the public to quickly see the benefits of bus improvements.

In a survey of local officials, the GAO also looked into the economic benefits of transit-oriented development (TOD) along BRT corridors. Most local officials thought BRT provided some economic boost but found it hard to quantify or separate from other factors, including the recession and other development going on in their cities. Most still thought rail was a better economic catalyst, in part because it’s perceived as more permanent. Another limiting factor is the fact that transit agencies might not own as much land around BRT stations as around rail stations, giving them fewer opportunities to directly incentivize TOD.