Last week, I published a list of seven questions I had as the Transportation Conference Committee started meeting. I was examining the politics, not the policy. Turns out some readers wanted to hear more about the policy.

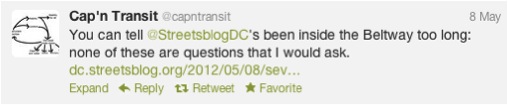

I asked the Cap’n what his questions would be. The reply:

Meanwhile, reader Ryan Richter sent in his revised list of questions too. They’re a little more specific, so I’ll start with Ryan’s. With any luck, the answers to Cap’n Transit’s questions will be woven into the answers below.

Thanks to both of you for keeping me focused on what really matters in this whole political hullabaloo.

Ryan’s first question:

1. How will public transportation fare after being practically decapitated in the last round?

Public transit came out a winner when members of the House GOP mounted their full-frontal assault against it. “The uprising was so immediate and so bipartisan [the Republicans] backed off,” said Deron Lovaas of NRDC. Democrats and some urban and suburban Republicans blew up at the idea that transit would no longer be eligible for its 20 percent of Highway Trust Fund dollars, which it’s gotten since the Fund’s Mass Transit Account was created under Ronald Reagan in 1983. Surviving an attempt against it makes transit that much stronger now – its opponents know that defunding transit is a losing issue for them.

The Senate bill keeps transit funding levels about the same as they’ve been but it makes some good changes to transit policy, like reducing delays in getting transit projects moving and prioritizing improvements to existing transit infrastructure. Perhaps most significantly, it allows transit agencies, under some limited circumstances, to use federal funds for operations instead of just capital. The restrictions on those funds have left some agencies with brand new buses and no way to pay drivers. Transit advocates have been asking for more flexibility in using these funds for years, and it’s reassuring to see that some relief could be coming.

The Senate’s MAP-21 also provides funding for TOD planning and would permanently restore parity between transit and parking commuter benefits.

Will all of these Senate provisions make it into whatever comes out of the conference? It’s impossible to know, but if I may turn back to inside-baseball Washington politics for a second, it’s worth remembering that the Senate is in a strong position to maintain many of its bill’s key elements. Technically, nothing should be introduced into a conference bill except for provisions in the two bills being conferenced, and there’s no real House bill to speak of. Plus, it’s very possible that the outcome of this conference will be no bill at all but another extension until the lame duck period after the election. But if there is a bill at the end of all this, Ryan also wants to know:

2. How do we handle the overwhelming state of good repair issues impacting all transportation infrastructure?

This is one place where the Senate bill shines. Transportation for America has a good write-up of the Senate bill’s State of Good Repair provisions, in which they applaud the new requirement that at least 60 percent of maintenance funds be used for actual maintenance, not new capacity. Allowing states to divert 40 percent of repair funds for new capacity still seems like too much, but they used to be allowed to squander up to 50 percent on non-maintenance projects.

Plus: “States are required to develop asset management plans,” wrote Steve Davis at T4America, “and as a part of these plans establish performance targets for the condition of roads and bridges and the performance of the system. In addition, the program includes provisions to hold states accountable for the repair of Interstate pavement and National Highway System bridges by requiring that they spend a certain amount of funding on the repair of those facilities if they fall below minimum standards established by USDOT.” And roads that fall under the National Highway System will go from about 160,000 to 220,000 miles. These maintenance requirements will help steer states away from building new highways that would only exacerbate sprawl.

The House bill (when there was a House bill) would have required better reporting and allowed for some penalties for deficient bridges but didn’t have the same restrictions on spending.

But Ryan, you asked about all transportation infrastructure, not just roads and bridges. As we referenced above, the Senate bill also includes the Core Capacity Improvement Project, which would expand funding eligibility to include improvements to the capacity and functionality of existing fixed guideway systems. And it directs U.S. DOT to “achieve a balance” between rail system development and improvement of the current system.

3. How does the bill recognize the long (and short) term societal trends towards transportation that does not include the automobile?

It doesn’t. Not really. It maintains the current four-to-one highway-to-transit funding ratio, it weakens programs to fund bicycling and pedestrian safety (even the Cardin-Cochran amendment is only a partial fix), and it doesn’t even contemplate land use. The Senate bill has some helpful provisions for rail (discussed more below) but nothing that will propel forward high-speed rail or even a substantially more robust and reliable non-bullet passenger rail network.

I hope you ask that question of elected officials, Ryan. It gets right to the heart of the problem. A future less dependent on cars (and road-building and oil) is where we’re headed. But even the Senate bill, which transportation reformers support (albeit not without reservations), only makes some thoughtful tweaks on the margins of the current system – it doesn’t substantially reform it.

Next question, Ryan?

4. What is the priority for high speed rail or any other long-term transportation infrastructure investments?

Strangely, the transportation bill isn’t the primary vehicle for rail issues – most of that is covered under the Passenger Rail Investment and Improvement Act (PRIIA). There is some movement to fold passenger rail into the transportation bill, but neither the House nor the Senate bills do that.

That’s not to say that these bills don’t address rail, but they’re not the place where a true high-speed rail network will be born. The Senate bill requires U.S. DOT to develop a long-range national rail plan, as well as regional rail plans that address implementation. If states want federal intercity passenger rail grants, they’ll have to follow suit. There are provisions to get next-gen equipment to more states and to make life a little easier for Amtrak (as opposed to the House, which has shown an interest only in killing Amtrak). The Senate, on the other hand, would expand the kinds of grants Amtrak can apply for (currently, Amtrak can only apply directly for high-speed projects), allow Amtrak to match grants with ticket sales, and create a 100 percent federal grant program for Amtrak and the states to improve or preserve long-distance service. It also allows Amtrak to take over responsibility for environmental reviews. The Senate bill also encourages on-time service by penalizing Amtrak's host railroads when they are to blame for consistently late train service.

The House’s H.R. 7, on the other hand, would have cut Amtrak’s operating subsidies, limit its use of federal funds, and deny federal funds to “low-speed” projects under 125 mph.

So what will the conference bill do? It will probably be a compromise, with Senate language that requires new spending especially vulnerable. Amtrak is a lightning rod in this Congress, though, and there could be big disagreements over any of it.

5. How will the bill address critical operational funding shortfalls (not to mention capital) that transit agencies are facing?

I’ve addressed some of this above, but the biggest help is the Senate’s allowance of flexible spending for operations during periods of high unemployment. As for capital, the changes to New Starts I mentioned are positive, but it all comes back to Ryan’s third question: Don’t expect this bill to radically shift the balance from car travel to anything else.

6. How will the bill address the structural financial problems facing the Highway Trust Fund?

Along with the answer to #3, this is probably the most pathetic part of this whole pathetic process. The bill doesn’t address the structural funding issues at all. It doesn’t raise revenues or put in place a more sensible or sustainable system. It doesn't create a National Infrastructure Bank to help leverage private investments. The House tried to tackle the problem by slashing spending, but that plan was soundly rejected by everyone involved. Then they said they could keep spending levels the same but raise revenues through oil drilling, which would be hilarious if it wasn’t so scary.

The complete paralysis around reforming the funding for transportation is exactly why this bill has been such a headache, and it’s why the Senate bill has to end in September of next year – that’s when the Highway Trust Fund is scheduled to go insolvent, and someone in Washington is going to have to show some real conviction of character to actually change something. But no one wants to do that yet. Which brings me to your last question, Ryan:

7. Will there be a push towards alternative user fees to fund transportation infrastructure?

Now you’re just depressing me. No. No, there won’t.