Have you had your morning coffee? Serotonin reuptake inhibitor? Fifth of whiskey? Whatever it is that gets your gears turning? Well, I hope so, because today we're going to have a look at the latest exercise in mind-bending obfuscation from New Geography's Wendell Cox.

This time, inveterate sprawl apologist Cox has taken issue with an op-ed written by Think Progress's Ryan Avent for the New York Times. In the piece, Avent, a former Streetsblog contributor, makes the hard-to-dispute claim that density contributes to productivity and economic growth in urban areas. But, Avent continues, anti-density NIMBYism in large coastal cities has contributed to a run-up in real estate prices that limits people's access to the urban core and threatens continued growth.

Avent's article is generating a lot of buzz. And every time someone writes something prominent about the usefulness of cities, Cox seems to be contractually obligated to write a response arguing that Phoenix is better than New York on any measurable statistic.

This is no exception. You should really read Cox's whole post over at New Geography just for the pearls of wisdom like this: "Cities (urban areas) do not get more dense as they add population. They actually become less dense." And this: "In fact, urban areas grow by dispersing, not densifying."

However flimsy, Cox's rebuttal garnered a response from Avent. At The Bellows, Avent writes:

Large portions of the United States — including economically critical areas — do get more dense as they add population. New York City didn’t get any bigger between 2000 and 2010, but it did add over 200,000 people. As a result, it got considerably denser. Had it been easier to build in New York City, the rising demand to live there would have translated into even more population growth in the core, and correspondingly less growth in housing costs. It’s funny that Cox understands that building regulations are a problem but doesn’t connect onerous restrictions in the core with growth on metropolitan peripheries.

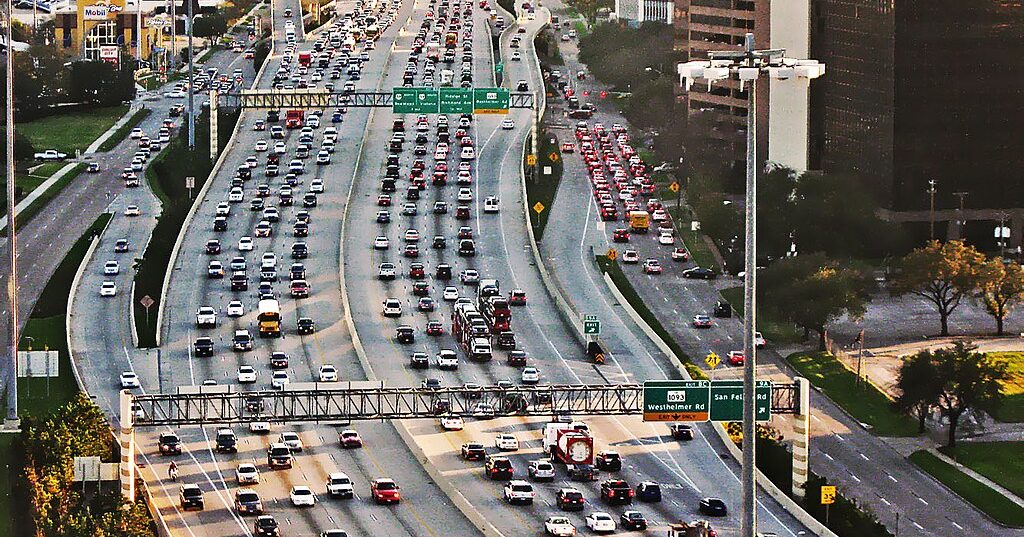

Cox also misunderstands another critical point of the piece, and of the book from which it’s adapted. He implies that higher incomes in dense, productive areas don’t count because they’re canceled out by higher living costs. That’s true; the point I’m making is that people are moving from more productive cities to less productive cities because of the impact of housing costs on real earnings. What Cox neglects is the importance of the fact that businesses in expensive cities are willing and able to pay high nominal incomes. Why would they do that if they didn’t have to? A tradable good or service produced in Silicon Valley will fetch the same price in an export market as a similar good or service produced in Houston. You don’t get to charge more for a widget just because you chose to make it in an expensive city. That’s a big reason why lots of employers choose not to locate their businesses in Silicon Valley, or indeed in the United States. But many of them do choose to locate in the expensive city and pay the high wage, and as I point out in my book, expensive places like Silicon Valley employ a larger share of American workers in high value, export industries than do cheap places like Houston.

They do this because it’s worth it to them to locate in the expensive city. Firms in Silicon Valley enjoy higher productivity levels and informational spillovers — facilitated by density — that simply can’t be duplicated in other, cheaper cities. If they could be, they would be, and the high cost Silicon Valley economy would quickly implode.

Elsewhere on the Network today: Decatur Metro writes that the Atlanta region's well-documented auto-centrism should be blamed for many regional active transportation failures, rather than the convenient scapegoat that is MARTA. Biking in Dallas shares one woman's joyful journey from cycling neophyte to living nearly car-free. And the Philadelphia Bicycle Journal carries an update on the continuing controversy over the city's plan to install a bike lane through Philly's Chinatown neighborhood.