With the House Transportation and Infrastructure Committee set to introduce its reauthorization bill the first week of July and the Senate EPW Committee already behind on its own timeline to introduce its own, think tanks and policy groups have a limited amount of time left to influence the process. The Bipartisan Policy Center got into the act yesterday with its report, “Performance Driven: Achieving Wiser Investment in Transportation.”

It's a sequel to a 2009 study laying out "A New Vision for Transportation Policy," which sought to divide all federal funding into two mode-neutral categories: system preservation (which would get 75 percent of all federal transportation dollars) and capacity expansion (which would take 25 percent).

The new report goes further to fully re-design the framework for how the BPC thinks the federal government should change the way it allocates transportation money. The authors take no position on how big the “pie” of federal transportation funding should be – they say their recommendations should guide how the pie is divided, no matter how big it is.

“This report takes as given the current revenue levels,” BPC Transportation Advocacy Director JayEtta Hecker told an audience yesterday at the report launch. “We’re not advocating for something there’s no receptivity for.”

“Given the bills that are being considered in Congress now, we wanted to be relevant to them,” said former Senator Slade Gorton, a co-chair of the BPC’s transportation project. Another co-chair, former New York Congressman Sherry Boehlert, said he would like to see a shift to a VMT fee and a significant hike in the gas tax in the meantime – but his view hasn’t prevailed, and so they’re stuck working with a small pie.

Many in Washington have turned to performance measures as an essential element of any transportation bill that includes lower levels of funding, in order to guarantee that those scarce resources are well-utilized. The BPC framework sets out specifically how the new system would work.

To start, the BPC recommends setting clear goals for the federal surface transportation program. BPC says performance should be measured against these five goals:

- Economic Growth

- National Connectivity (connecting people and goods across the nation)

- Metropolitan Accessibility (providing efficient access to jobs and other services)

- Energy Security and Environmental Protection

- Safety

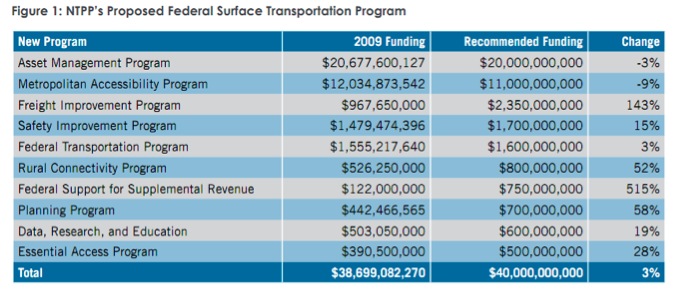

Starting from there, BPC recommends consolidating the 108 current federal transportation programs into 10 mode-neutral new programs:

These programs, as laid out here, don't exist now, so the 2009 funding number is based on current programs that would be folded into these new categories.

Ninety percent of funds would still be distributed by formula, and although BPC authors consider current formula factors "terrible," they used them as the basis for this plan, which is a short-term plan they'd like to see adopted quickly. For the longer term, they advocate crafting new formula factors, but one staff member said that the last time they tried to recommend new ones, they were "summarily ignored."

So if they're still distributing money via the old formulas, where does the performance aspect come in? First, the other 10 percent of the money is made up of various "bonus" programs, which are discretionary. BPC hopes that by holding out the 10 percent as reward money for using the other 90 percent well, they can help steer the vast majority of funds toward more effective uses. Also, they call for beefed up planning, which they hope will help guide states and metros toward more outcome-oriented projects.

The BPC gives a whopping 515 percent increase to something they call Federal Support for Supplemental Revenue, which consolidates the TIFIA loan program and other federal technical assistance programs. It increases the TIFIA cap from $110 million to $450 million. Schank noted that Sen. Barbara Boxer (D-CA) wants to increase the cap to $1 billion. JayEtta Hecker explains why:

TIFIA is a loan guarantee program, and it’s only effective in leveraging because it has very strict standards for credit-worthiness. And frankly, it’s our view, having looked at the pipeline, looked at the processes, looked at the environment out there and the readiness of different projects to come forward, that $450 million is a pretty sustainable and reasonable and robust level to expand TIFIA.

They also suggest expanding tax incentives and reducing limitations on the ways states can raise funds – specifically, they recommend removing barriers to tolling on interstates.

Freight improvements get a 143 percent jump in funding under the BPC plan. “We really don’t have a national freight policy,” said Hecker. “This is too much a central part of our national interest to wait until a whole plan and metrics and a whole strategy can be put together.”

Joshua Schank, formerly a fellow at the BPC’s transportation program and now head of the Eno Transportation Foundation, said federal funding should be limited to programs that are a “federal responsibility.”

That kind of language can make bike and pedestrian advocates nervous, since conservatives often argue that active transportation is not a federal responsibility. Consolidation of programs also poses its own risks, as programs like Safe Routes to School and Transportation Enhancements stand to lose their own dedicated pot of funding. Schank tried to reassure them.

“‘Mode-neutral’ includes bicycles and pedestrians,” Schank said. “We don’t put any restrictions on that. If a state or metro feels it can accomplish the goals we’ve set out through investment in bicycle and pedestrian, by all means they should be free to do so.”

Of course, states and metros have always been “free” to allocate more money for bike/ped facilities -- and advocates have still found it helpful to have a federal mandate.

The BPC also targeted a few programs for total elimination, including the Equity Bonus program, the single largest federal highway program, whose sole purpose is to appease angry “donor” states that don’t get back as much in federal transportation money as they pay in fuel taxes. The Equity Bonus ensures that most states get back at least 92 percent of what they pay -- creating a perverse incentive for states to encourage maximum fuel consumption.

There are some things BPC wants to keep a set-aside for. They would reward states and metros for bringing their own money to the table and leveraging other investments -- and for using congestion pricing.

“How did we pick congestion pricing, out of all the things you could incentivize?” Schank said. “When it comes down to us, many of our goals and perforance measures, it is hard to imagine how they could be achieved in the absence of better pricing of our roadway system. It is hard to imagine how the Metropolitan Accessibility [goal], particularly, could be achieved without better pricing of our roadway system.”

Performance standards present problems for states and metros that haven’t been doing a good job of collecting data. Last month’s Pew/Rockefeller report found that 19 states were far behind in their ability to gather information that would help them – or the feds – evaluate the outcomes of their transportation spending. Schank said the BPC plan calls for reducing and streamlining reporting requirements, to the point where he thinks the new plan will be less burdensome than the current system, despite the heavy emphasis on proving the effectiveness of the money spent.