It’s payback time again for state DOTs. The fine print on the jobs bill Congress just passed includes a $2.2 billion rescission from state transportation funding, and projects to make biking and walking safer are especially at risk of losing out.

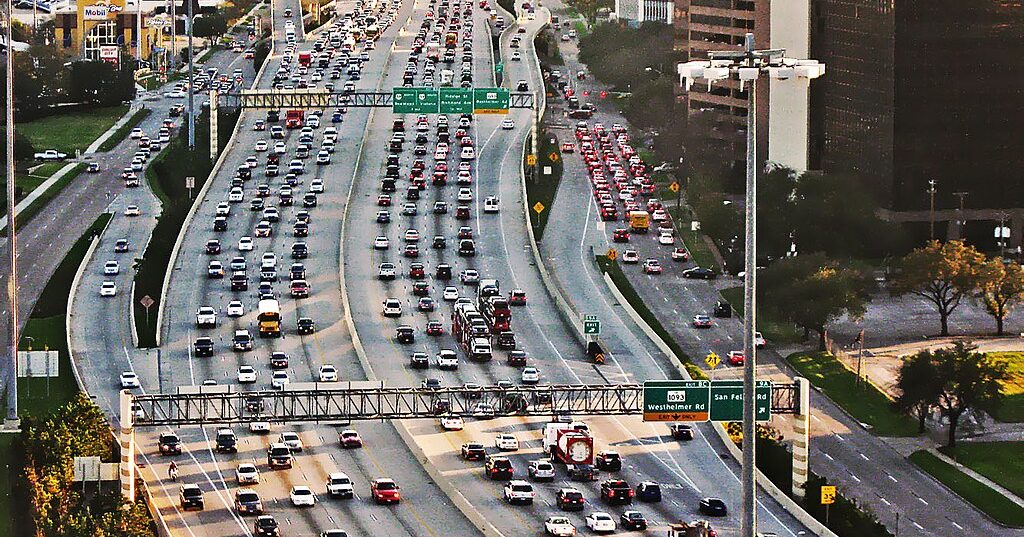

State DOTs have to return funding to the feds, and programs to improve biking and walking are especially at risk of getting scaled back. Photo: Tanya Snyder

State DOTs have to return funding to the feds, and programs to improve biking and walking are especially at risk of getting scaled back. Photo: Tanya SnyderThis isn’t coming out of the blue. It’s part of a game Congress played five years back, when they approved more transportation funding than the White House would allow. They left the bigger number in the bill, only to periodically ask the states for some of it back in the form of rescissions. Now is one of those times.

But here's what’s getting bicycle and transit advocates worried: This time, the money could come disproportionately from bike and pedestrian improvements.

“This is different from the other rescissions in a few ways,” said Caron Whitaker of America Bikes. “One, the other rescissions were subject to a proportionality clause to ensure that certain programs weren’t hit disproportionately, because they had been cut disproportionately in earlier rescissions. Two, this doesn’t cover same breadth of programs as the other ones did.”

Off-limits this time around are funds for the Highway Safety Improvement Program, the Railway-Highway Crossings Program, the Surface Transportation Program, and Safe Routes to Schools.

That means there are fewer programs left on the chopping block, increasing the chances that bicycling and transit programs will be affected -- and there are no rules saying state DOTs have to play fair.

That’s what makes this a particularly scary rescission cycle. It’s not the biggest bite -- last year states were faced with rescissions four times this size -- but some advocates see bull’s-eyes painted on programs that invest in non-automotive modes.

“We’ve seen New York state, for example, rescind a disproportionate amount out of some programs we really like, like CMAQ (Congestion Mitigation and Air Quality Improvement Program) and [transportation] enhancements,” said Michelle Ernst of the Tri-State Transportation Campaign.

The rescinded money comes out of states’ “unobligated balances” -- money that’s been authorized but hasn’t been spent yet. Ernst says it makes sense to take it out of the National Highway System instead of bicycle and pedestrian programs. If nothing else, it makes things simpler.

“The other advantage of cutting it from a road program versus a bike program,” Ernst said, “is that bike programs tend to be much less expensive. So you may have to cut or postpone ten separate bike projects in order to meet that rescission, whereas maybe you have to postpone just one road project.”

The feds are encouraging state DOTs to listen to stakeholders when making these hard decisions. Local bicycle advocacy groups, like WABA in Washington, DC, are trying to make sure their voices are heard.

“There is direction from Federal Highway to the states encouraging outreach to stakeholders, but not requiring,” says WABA Director Shane Farthing. “People should contact state level DOT folks and their governor or mayor.”

Time is of the essence. States have only until August 25 to decide what stays and what goes.