It's not too late for Americans to get the world-class transit networks they deserve — and it wouldn't take as long or cost as much as we spent building the highway system, a new analysis finds.

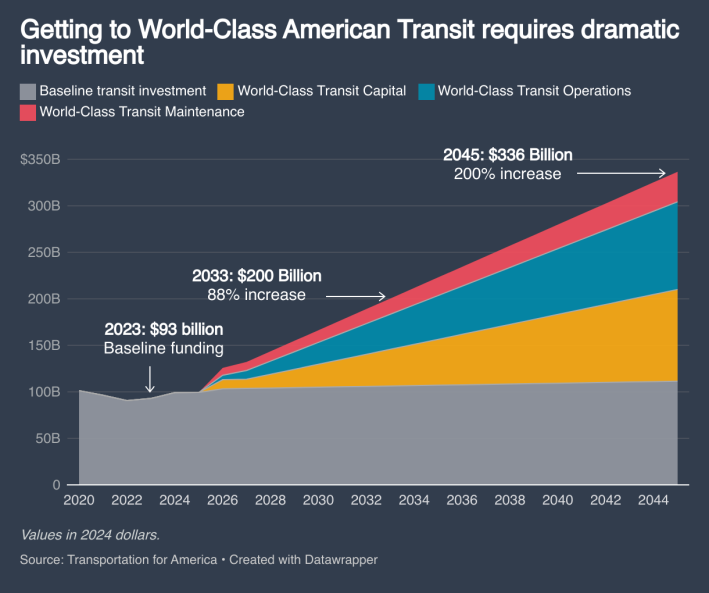

A new analysis from Transportation for America found that a $4.6-trillion "moonshot" over the next 20 years would be enough to bring the transit networks in most American cities up to par with world-class communities like Berlin, Paris, Oslo and Buenos Aires, which all have more than 115 transit vehicles on the street and underground per 100,000 residents — not to mention excellent service and dedicated rights-of-way to match.

The average U.S. city, by contrast, has just 27 buses and trains per 100,000 people, which is an international embarrassment by comparison.

Considering that it would mean tripling the national transit budget, spending $4.7 trillion in 20 years might sound like a big ask — except that America is already on track to spend an additional $6.3 trillion on highways over the next two decades. Since the Federal Highway Act of 1956, the country's already spent $9.6 trillion more on moving drivers than moving people on shared modes, creating a massive network of autocentric roads that many experts agree is already so badly overbuilt that many states cannot afford to maintain it, with little to show for it besides stratospheric road deaths, stubborn congestion, and dangerous levels of air pollution.

As the balance of the Highway Trust Fund continues to plummet — and with Congress due to pass a new federal transportation law that could replace that broken system in September — the study authors say the moment is ripe to put all the "America First" rhetoric to use and reclaim our place at the top of the global hierarchy of transit-building nations. Or at least, to recognize what an astonishing global outlier we are when it comes to giving people basic transportation options, and finally do something about it.

"This is something that we've fallen behind on in global leadership, and it's a policy choice that hasn't delivered for us," said Corrigan Salerno, the lead author of the report. "All these other countries are able to get significantly better per-dollar investment benefits for their infrastructure by investing in compact growth and transit."

To understand just how far American transit lags behind its peers and how to close the gap, Salerno used the number of transit vehicles per capita as a rough proxy for how well its residents are served by their local networks. And while he acknowledges that's not a perfect approach, in part because cities with walkable, bikeable neighborhoods may not need as big a stable of buses and trains, he argues that's probably the most comparable data we've got about transit around the world — and the top-ranking cities do mostly track with what many people would subjectively consider some of the best transit systems, too.

"If you've ever traveled to places that have [great transit], you know you what that looks like," he added. "You're able to get where you want to go, to do your daily errands. ... If a place has a high number [of transit vehicles per capita], we tend to feel it in our daily mobility experiences, which give us a high level of freedom. And if it's a low number, we feel locked into the car."

Car dependency has also locked countless U.S. households into paying for transportation they can't really afford. The study authors estimated that if we keep pouring asphalt this rate, American households will spend more than $77 trillion on car ownership between 2026 and 2045 — an unthinkable sum that few affordability advocates have really bothered to challenge.

If a moonshot $4.6-trillion transit investment could reduce the rate of car ownership by just one-quarter of a percent each year — a rate which the study authors say is "conservative" – the analysis estimates it would save Americans over $5.4 trillion just from the costs of car ownership that could be avoided — meaning that taxpayers' investment would more than pay for itself.

"That would translate to real savings for folks and actual freedom to choose how they want to spend their money, rather than being forced to spend it on transportation," Salerno added.

Moreover, all of those savings would be on top of the billions of dollars governments could save by shifting money to modes that are less expensive to maintain, rack up fewer public health costs by killing fewer people, and stimulate economic activity more than building roads only for drivers. And that means money to devote to other priorities like healthcare, education, and more.

Salerno acknowledges that some might argue America has gone too far down the autocentricty rabbit hole to pull itself out now, even if Congress and local communities somehow all agreed to collaborate on a moonshot moment. He points out, though, that some urbanized areas are far closer to World Class status than they might think — and not necessarily the ones that you'd guess.

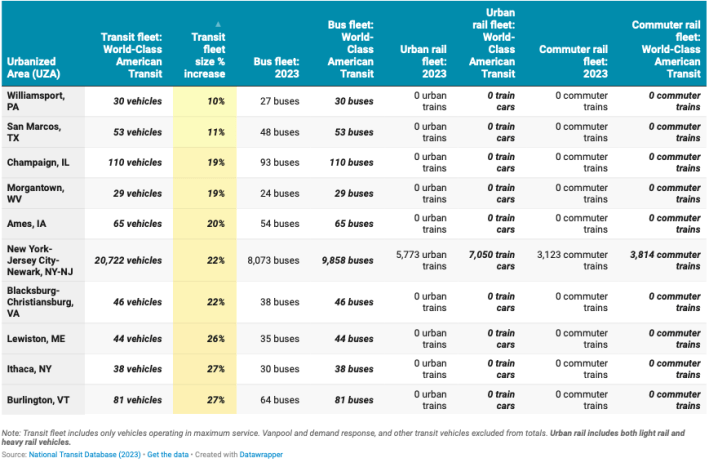

In an analysis of all U.S. urbanized areas over 50,000 people, Salerno found that places like Williamsport, Penn., San Marcos, Texas, Ames, Iowa, and Morgantown, W. Va. all would need less than a 20-percent increase to their local transit fleet to make them competitive with the rest of the transit-riding world (though, to be fair, Morgantown gets a big boost from its controversial personal rapid transit system.)

The transit-leading metro area surrounding New York City also doesn't have far to go, either, requiring less than 100 miles of new bus rapid transit lanes to bring them up to the global par — and Salerno points out that's largely because relatively car-dependent Newark and Jersey City are lumped into their numbers, and the fact that all cities on the list were adjusted for relative density.

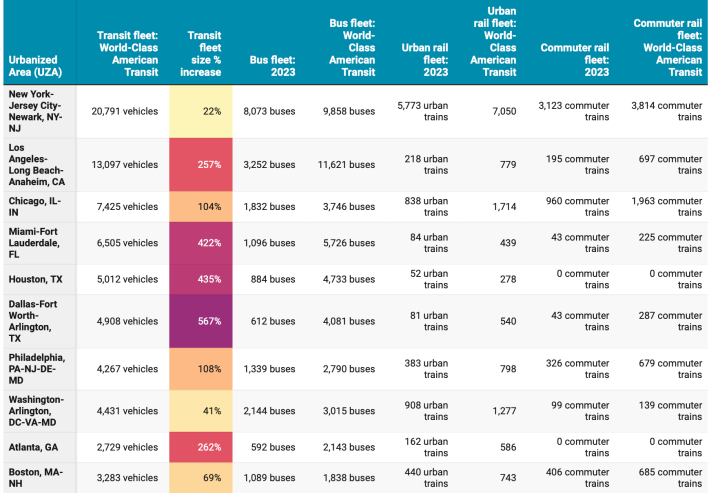

Those are rough estimates, but the report authors say it's important for US residents to see just how close their communities might be to a transit revolution — and how even big numbers, like adding 11,621 buses to the streets of metro Los Angeles, are actually fairly attainable relative to the heaven and earth we routinely move to accommodate more car traffic, even decades after we proved that doing it doesn't cut congestion. And he particularly encourages advocates to find their own metros to help make that case to transportation leaders.

"When we have these kind of big numbers, It helps put into perspective what actually is the norm for other cities outside of the United States," Salerno adds. "[Having a certain number of buses] means reducing 30 minute headways down to five minutes on certain routes; it means ensuring that entire new areas are covered by that transit service. ... It's [transit as an] actual, viable feature in the community."

Of course, it will take a lot more than just buying buses and building train lines to truly transform America into a transit titan. The analysis also explores how increasing service and overhauling transit maintenance might look in a moonshot scenario, while acknowledging that rethinking land use to put all those new bus and train stops within easy reach was too much for this particular report to tackle.

Salerno also acknowledges that such a bonanza for buses and trains would require an incredible imagination just to fund, which the report didn't have space to delve into — though considering that 85 percent of all ballot measures for transit have passed in recent years across communities of all sizes, the public appetite for that conversation is clearly strong. And while raising trillions would need to involve the federal government, he points out that if we did it for highways 70 years ago, we can do it again for the shared modes that Americans are actively demanding.

"We're hoping to start a discussion about what types of policies would be needed for this level of urban transformation," he added. "[And it needs to be at] the same scale and ambition as what we had for the Federal Aid Highway Program, where we instituted a massive, never-before-seen tax on drivers. We accepted that bargain because it was building out something we had decided was worthwhile. We would need for the same thing for transit."