America has poured enough asphalt to build its sprawling auto-centric road network to cover the entire nation of the Netherlands, according to a new study — and in the process sacrificed trillions of dollars worth of land that could have been put to better uses like housing.

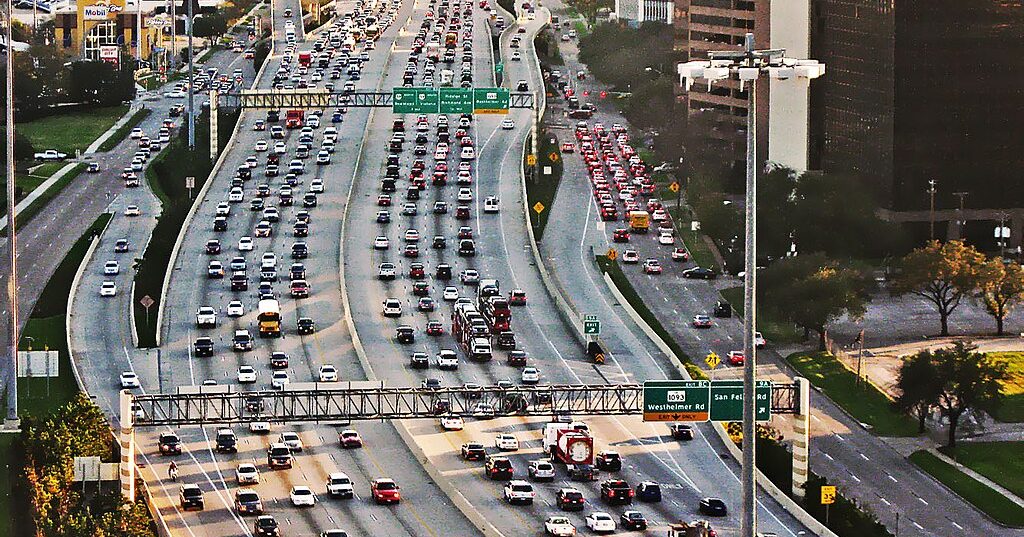

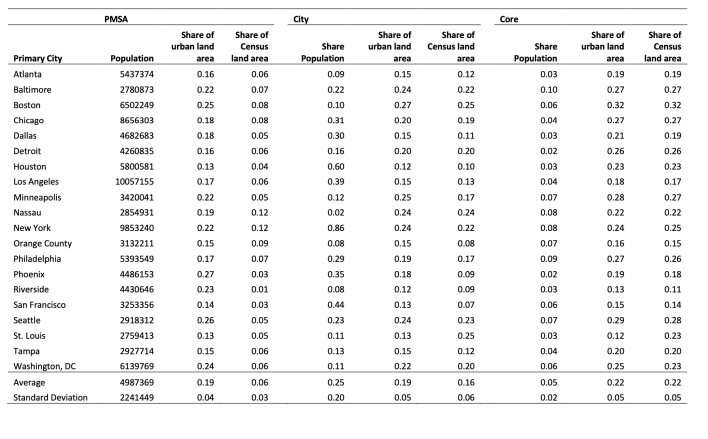

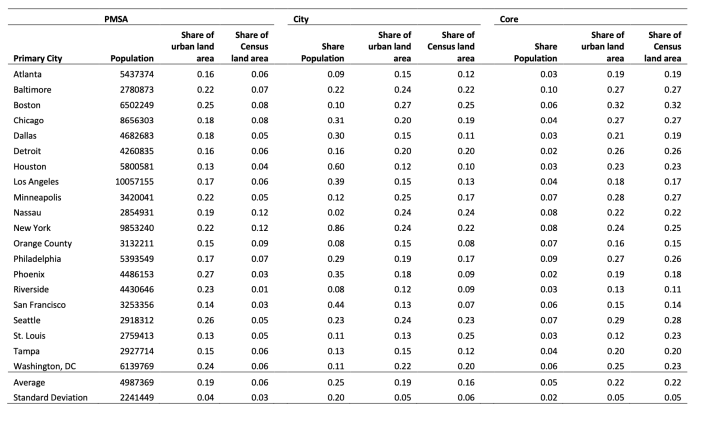

U.S. metros were home to a collective total of more than 22,000 square miles of roadway by 2016 — or about 21.7 percent of all land in U.S. cities and towns, according to the fascinating new paper in the Journal of the American Planning Association.

That's "roughly the size of West Virginia," researchers said. If it were a country, it'd be around the size of Norway, bigger than 68 percent of nations on earth. And doesn't even include all the roads that we've built or expanded since 2016.

Considering that states currently spend about 25 percent of their guaranteed federal infrastructure dollars on expanding highways every year, that eight-year bump could be significant. It also excludes sidewalks, bike lanes and on-street parking — never mind off-street parking lots, garages and driveways or the long stretches of highway that run between the county's 316 primary metropolitan statistical areas.

Put it all together, and the researchers estimate that all the urbanized land we devote to roads is worth $4.1 trillion, or 22 percent of American gross domestic product. In the densest cities in particular, that represents a goldmine of potentially re-developable parcels — if policymakers only recognized the shocking opportunity costs of dedicating so much space to drivers.

“I think there's a tendency to view the land [upon which our roads are built] as free — to not acknowledge that it might be put to better uses, like housing and shops and parks and other things that we care about," said Erick Guerra, associate professor at the University of Pennsylvania and the lead author of the paper. "I mean, hopefully we care about [those things] more than asphalt; the whole point of the transportation system is to get us to shops and offices and houses and parks and friends.”

Dude, where are my roads?

Part of that tendency, stems from the simple fact that U.S. residents just don't know how much of their communities are devoted to cars, Guerra said.

While federal databases tend to track the length and type of roads in America's inventory, they don't always track their width, even as America's highways swell to as many as 26 lanes. Meanwhile, researchers have struggled to use more granular data sources like satellite imagery and parcel data to get a birds-eye view of just how much bitumen is really coating our country.

Even individual states, regions and cities don't usually track how big their road networks are getting, in part because they often aren't required to fix existing infrastructure before they use federal money to build more.

That essentially strips communities of any meaningful incentive to take stock of their blacktop — especially as powerful interests from the highway-building lobby keep pushing the widely disproven myth that widening roads cures traffic jams, which in turn pushes policymakers to keep the road construction crews running.

Add in the fact that American driving lanes tend to average between 10 and 12 feet wide — compared to just 8 to 10 feet in Europe, which studies show discourages high speeds and makes roads safer — and many U.S. communities are essentially drowning in pavement.

"Roadways are one of the most common ways that we use land," Guerra said. "Take housing — if you get rid all the yards, then there's actually more space dedicated to roadways [in America than to places to live]. If we're looking purely at impervious surfaces, there's more space dedicated to roadway than there is to housing or apartments."

How much excess asphalt really costs us

In housing-strapped cities, of course, all those extra lanes on deadly urban arterials and highways ripping through the hearts of downtowns aren't just polluting our skies. They're essentially gobbling up precious space that could be used to put roofs over people's heads and services in their neighborhoods — without even getting drivers where they need to go any faster once the principle of induced demand takes hold.

For some communities, the costs of that choice are truly staggering. In the core neighborhoods of New York City, for instance, the researchers estimated that a whopping 22 percent of urban land area is devoted to automobile movement. If all that land were valued similarly to the developed parcels that sit right next to them, it'd be worth $287,525 per capita on an annualized basis, they said.

When the researchers compared that number to transportation officials' own calculations of the "time savings value" drivers theoretically enjoy when we add extra lane to speed up their commutes — formulas that, again, are widely disputed — they found that the potential development value of that land was still higher than the money drivers would allegedly save by getting to work faster.

That holds true in communities across the country, even in struggling cities where increasing car dependency and the generations of "white flight" it helped enable have eroded downtown real estate values. And when the researchers included the negative externalities of widening roads — like increased public health costs from crashes and pollution-related diseases — the difference was even more stark.

"Ignoring externalities and land values entirely, the costs of expanding urban roadways exceeded the benefits by a somewhat modest 17 percent," the researchers wrote. "Including the land value, costs outweighed benefits by a factor of nearly three; including externalities resulted in costs that were four to five times higher than benefits."

Imagining an end to overbuilt roads

Of course, turning excess lanes into buildings and parks can be a logistical and political challenge, Guerra acknowledged.

America's efforts to turn downtown highways into boulevards have met waves of resistance, whether from skeptical drivers and DOTs or the descendants of the people — who were displaced to build those roads in the first place and fear there will be no place for them if the grid is restored and region gentrifies.

Even in the handful of U.S. cities that weren't overwhelmingly rebuilt around the automobile, reimagining roads can be struggle because streets are so narrow that there's less space to redevelop.

Guerra argues, though, that even pre-war cities like Philadelphia — where he lives — do have a lot of extra asphalt to work with. When his team did the math, they found that big, dense cities often dedicate a greater share of their total land to cars than smaller communities do.

“People in Philadelphia often say, ‘our roads are too narrow, so we can't put in bike lanes, or dedicated bus lanes," he he. "But one of the things that we found is that the share of space we dedicate to roadways in Philadelphia isn't that different; it's just the organization of the blocks that's a bit different. We tend to have more streets, but they're narrower relative to places like San Francisco or New York. There's space; you just kind of have to think about streets in pairs, as opposed to streets in isolation."

If U.S. communities can grasp how much the land under their auto-centric roads is really worth, Guerra hopes they'll embrace the opportunity to reimagine them around better uses — and meet the social challenges of that work head-on. Some advocates argue community land trusts and anti-displacement measures can help ensure that residents near newly-reduced roads can afford to remain, and communities that have been historically harmed by highways and other roads canned should be given first priority for new housing opportunities.

And if that kind of redevelopment truly isn't in the cards, Guerra at least hopes that cities will give some of their lane space back to sustainable modes. Many experts say active and shared transportation generate far more positive externalities for public health and the climate than driving, which can help offset the opportunity costs of failing to put buildings and parks on that land.

“Our default ought to be, 'More space for things other than roadways,'" he added. "[Because right now], the default is, ‘Widening a highway is likely to be good.’ I think the default should switch. [We should have] the assumption that that a bit less [roadway] is almost certainly worth more.”