This article was originally published in the Vision Zero Cities Journal, released as part of Transportation Alternatives’ 2025 Vision Zero Cities conference, which will take place October 28-30 in New York City.

Across California and the nation, a paradox is developing around the relationship between street safety advocates and the fire service.

On one hand, firefighters and paramedics have dedicated themselves to serving their communities, and they do so every day with skill and care, without hesitation, even under the most trying circumstances. On the other hand, street safety advocates are finding themselves at odds with fire departments and local firefighter unions over efforts to protect pedestrians and cyclists through the redesign of streets.

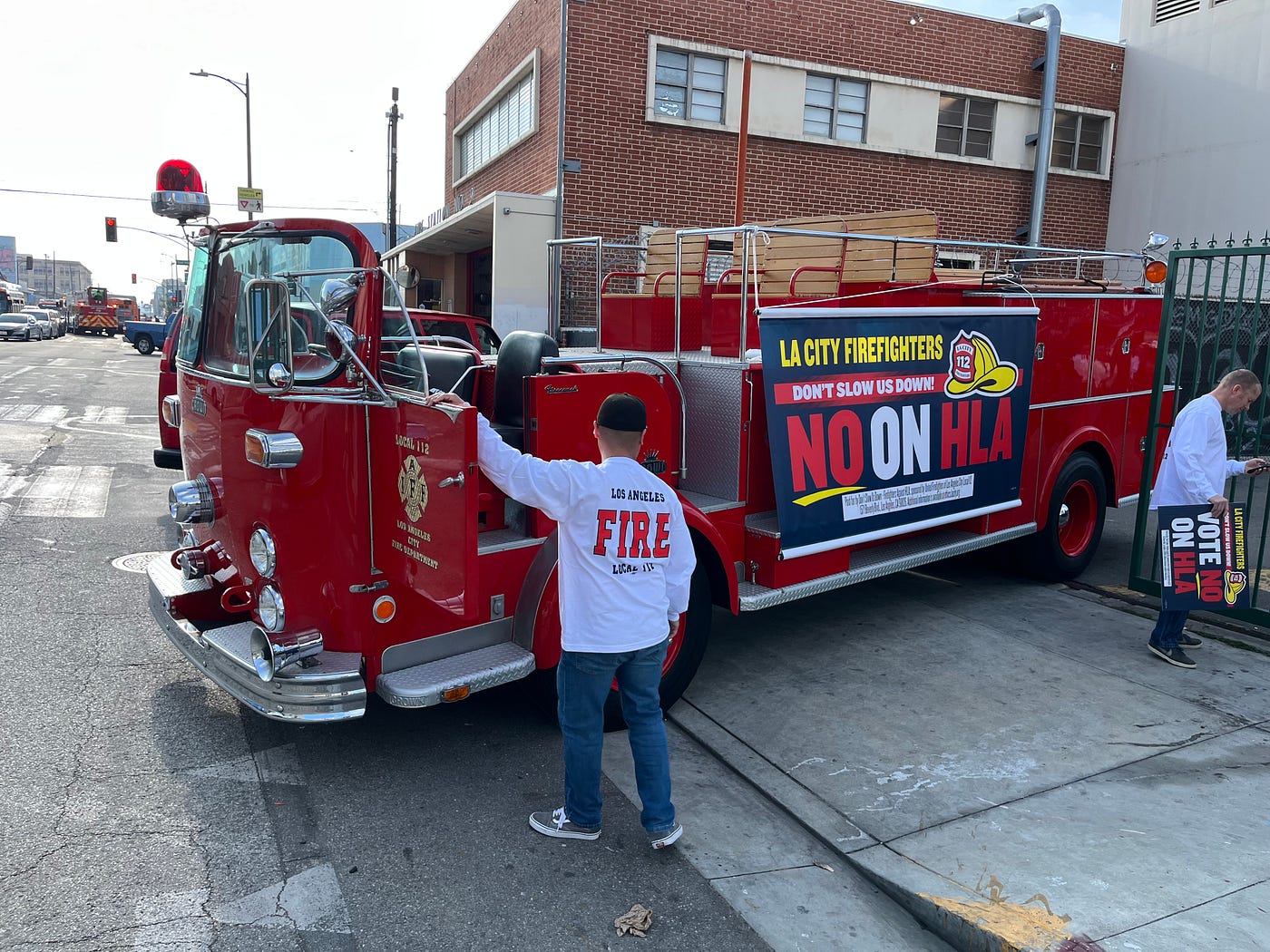

In Los Angeles, for example, the United Firefighters of Los Angeles Local 112 opposed the 2024 Healthy Streets LA (HLA) ballot initiative, which called for the installation of hundreds of miles of new bike lanes, bus lanes, and other improvements on designated boulevards. After voters approved the measure by a wide margin, California Assemblymember Chris Rogers doubled down, introducing AB 612, the “Increase Fire Department Authority Bill,” which proposed giving greater veto power to fire departments if street design changes could potentially affect response times.

The bill failed, at least in part due to the opposition of street safety advocates, but it will likely reappear in a coming session. Conflicts between fire departments and street safety advocates have occurred in other cities, including Oakland, San Francisco, Baltimore, and New York City, to name a few.

On one level, the opposition of the fire service is understandable. Their job is to reach people quickly and help them, so they may be skeptical of roadway redesigns that deliberately encourage slower travel. Certain lane redesigns, hardened bike lanes, and pedestrian bulb-outs, for example, might invite this criticism.

On another level, however, this opposition is at odds with the fire service’s own remarkable legacy of prevention.

Fire prevention emerged as a core function of the fire service after the 1974 America Burning report of the National Commission on Fire Prevention and Control, which found that across the nation, 95 cents of every dollar spent on fire services was used responding to fires, and only about five cents was spent on preventing fires from occurring in the first place. Nearly 8,000 people were dying in structure fires each year as a result. The fire service responded to the report by launching a stream of fire prevention programs and codes that, between 1980 and 2023, resulted in a 43% reduction in fire-related deaths nationwide, saving more than 5,000 lives over this period.

Nearly 50 years later, the fire service is well-positioned to apply its prevention expertise to the growing problem of street trauma, which now accounts for far more emergency calls than structure fires. For example, while pedestrian fatalities nearly halved between 1980 and 2009, national trends show a 74% increase in pedestrian fatalities from traffic collisions between 2009 and 2024, with a spike in 2022 representing a 40-year high. In comparison, all other traffic fatalities increased 8% from 2009 to 2024.

If it were to align its current approach to street trauma with the historic success of its fire prevention work, the fire service could emerge as a powerful advocate for street trauma prevention.

Every firefighter and paramedic knows that the trauma experienced by vehicle occupants, pedestrians, or cyclists in a crash can cause immense suffering and financial hardship, and that — like structure fires — preventing these incidents is far preferable to simply responding to them as they occur. Street trauma prevention is also key to stabilizing and reducing the growing number of EMS calls that are taxing fire and EMS systems in cities across the nation.

We also know what works. Between 2000 and 2012, the expansion of protected bike lane networks reduced fatalities for all road users by 61% in Seattle, 49% in San Francisco, 40% in Denver, and 38% in Chicago. Site-specific interventions like pedestrian median islands and road diets can similarly cut crashes in half.

Combined, these streetscape interventions create a redundant system of safety protections that dramatically reduces the likelihood of a serious injury or fatality. By making it genuinely safer for people to leave their car behind and walk or ride, these changes also hold the promise of reducing the congestion that is a common source of frustration — and delay — for firefighters and paramedics.

There is emerging evidence that at least some designs that reduce vehicle speeds, such as moving from four lanes to one lane in each direction, have little to no effect on fire and EMS response times.

Finally, responding to critically injured persons also takes a toll on the mental health of firefighters and paramedics.

In California, Senate Bill 542 created a rebuttable presumption that post-traumatic stress injuries among firefighters and police officers are work-related and thus compensable under workers’ compensation. The bill, signed by Governor Gavin Newsom in 2019, drew from the evidence, pointing out that “trauma-related injuries can become overwhelming and manifest in post-traumatic stress, which may result in substance use disorders and even, tragically, suicide.” The bill also reported that “the fire service is four times more likely to experience a suicide than a work-related death in the line of duty in any year.”

In my 13 years in the EMS and fire service, I certainly experienced a handful of calls involving young children that affect me to this day, more than 25 years later, as if they happened yesterday. Reducing the frequency of exposure to people who have been critically injured on the street is a more effective response to this reality for firefighters and paramedics compared to after-the-fact counseling and workers’ compensation payments for mental health support.

In 2024, this multifaceted prevention perspective informed the work of the Berkeley Fire Department and the city’s Disaster and Fire Safety Commission in launching the nation’s first Street Trauma Prevention program. The fire chief, Dave Sprague, also viewed the program as a way to help contain the more than 16,000 calls for service the department runs each year in the city of 128,000 residents.

The new program’s manager is responsible for working with other city departments to integrate the department’s response needs with prevention strategies, including in the design of street safety improvements that the City of Berkeley is deploying to prevent the collisions that injure nearly 700 motorists, cyclists, and pedestrians each year, on average. This injury rate far exceeds the two persons injured each year on average in structure fires in Berkeley, a fact that informed a year-long discussion among the fire administration, the firefighters’ union leadership, Walk Bike Berkeley, and the Commission.

Berkeley Fire’s program is groundbreaking for street trauma prevention, yet it can also be seen as the logical continuation of a prevention lineage that has defined the fire service for nearly fifty years. Many thousands of lives could be saved in the coming years if fire services across the nation could see this proud legacy and apply it to protecting vulnerable road users through proven prevention strategies.