Editor's note: a version of this article originally appeared on The Transit Guy and is republished with permission.

I’ve gotten plenty wrong over my years as a transit advocates, especially when it comes to how I talk about transit and what I assume about people’s choices. Some lessons came the hard way (and yes, my reply guys are always quick to remind me). Others came slowly, as I realized my own assumptions didn’t match reality.

These are some of my lessons, my mistakes, not a critique of anyone else’s work. But if they sound familiar, maybe you’ve made them too.

“People choose not to ride transit”

Years ago, I believed that if someone drove instead of taking the train or bus, it meant they were rejecting transit. That not riding was an active choice against it.

I couldn’t have been more wrong.

Transportation isn’t a binary; it’s a marketplace. People weigh their options and pick what works best for them in that moment, whether that’s transit, a car, a bike, or walking.

- I walk to get coffee because it’s just a few blocks away.

- I drive to a concert because the bus stops running after 10 p.m. and parking is cheap.

- I take the train to the airport because it’s frequent and parking there is expensive.

- I bike to school because there’s a secure locker and the neighborhood bike path takes me right there.

Even my own family lives in a suburb so car-dependent that they often drive to walk — yes, read that again. When they visit me in New York, they take the train because traffic on I-95 and parking near my place is a nightmare. But at home, they’ve never boarded the bus that stops 250 feet from their front door.

And it’s not about money, either. The New Haven Line, the busiest commuter rail in the country, serves some of the wealthiest communities in America. Riders aren’t on the train because they can’t afford to drive; they’re there because it’s faster, easier, and less stressful than the alternative.

The lesson: people don’t “reject” transit. They reject inconvenience. They will take the train or bus when it works for them, however they define convenience.

“Making driving difficult will make people take transit”

At first, I thought the solution was obvious: make driving harder, and people will take transit. Close streets to cars. Toll them into oblivion. Problem solved, right?

Not exactly.

Yes, restricting car access can work, but only if the alternatives are better or at least equal to the convenience of driving. If not, you’re just forcing people into a choice they resent, which builds bad will toward the very movement trying to help them.

A car-free street in a dense neighborhood with robust transit is almost always a great idea. But a car-free street in a car-dependent suburb? That’s a chicken-and-egg problem. Without first giving people a viable way to get where they need to go, all you’ve done is remove the only option they had.

The lesson: work with people, not against them. Understand where they’re coming from. Don’t end the conversation with “just take the bus” if, in their view, or in reality, the bus doesn’t work for them. Fix the gaps. Improve the service. Build the coalition before pushing for the end result.

“People who live in the suburbs reject urbanity”

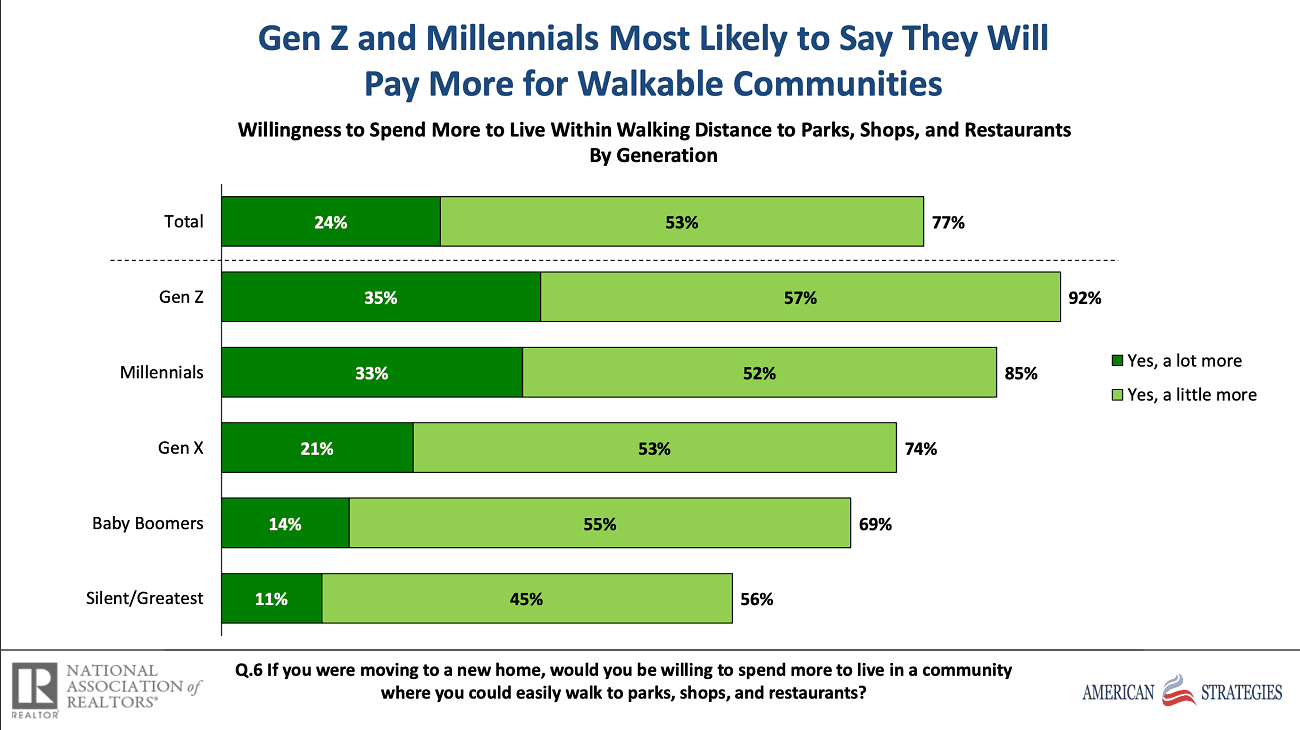

I used to think suburban living was an outright rejection of city life. If you wanted walkability, transit, and density, you’d live in the city. If you didn’t, you moved to the suburbs. But that’s not the whole story.

For many people, especially younger families, the suburbs aren’t a rejection of urban amenities; they’re the only affordable option left. In cities like New York, starting a family without a massive income or generational housing is nearly impossible. The housing stock for families just isn’t there.

So people move outward. Not because they hate cities, but because they can’t afford to stay. And here’s the kicker: a lot of them still like the city. They come in for work, for dining, for culture. They just can’t make it their home.

It’s a systemic failure, not a personal choice. Our inability to build enough family-friendly housing in urban areas pushes people out, and then we write them off as “anti-urban,” which only deepens the divide between city and suburb.

The lesson: don’t assume people in the suburbs are “the opposition.” Many of them want the same things transit advocates want. They’re just stranded by a broken housing and transportation system. (And yes, there are some

“All transit is good transit”

This couldn’t be further from the truth.

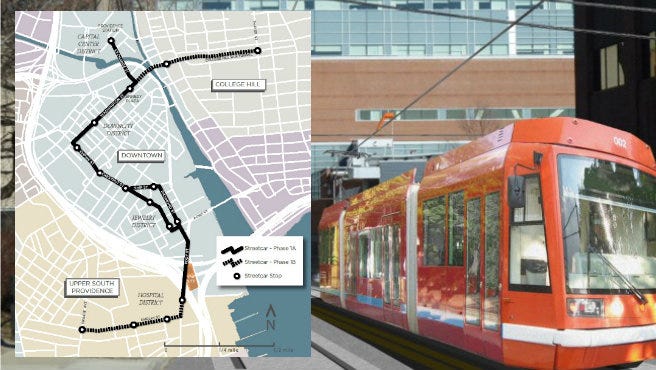

As a younger advocate, I fell hard for the Obama-era streetcar craze. In my hometown, I vocally supported the Providence streetcar project, a $100 million proposal for a 2.5-mile, mixed-traffic line through downtown, running peak service every 12.5 minutes.

At the time, I thought more transit is always good transit, and the shinier the better. I believed the streetcar would spark a renaissance for transit in Rhode Island. Instead, the project collapsed, and RIPTA pivoted. With a $13 million grant, they built a downtown bus priority corridor: large stations, real-time signage, signal priority, and interlined routes that now run far more frequently than the streetcar ever would have.

Do I believe Rhode Island deserves urban rail? Without question. But a slow, inflexible streetcar that barely moved people across Providence wasn’t the answer. Sometimes a transit project is just flawed, and calling it “transit” doesn’t automatically make it worth doing.

The lesson: More or new isn’t always better. If transit isn’t useful, frequent, or convenient, then building it for the sake of building it doesn’t make sense.

Advocacy isn’t about pretending you’ve always been right. It’s about learning, adapting, and bringing those lessons into the fight for better transit and better cities. If we can do that together, the future will be stronger than the mistakes we’ve left behind.