In 1974, to conserve fuel amid a global oil supply crisis, federal lawmakers established a national speed limit of just 55 miles an hour. For inventor Michael Valentine, though, that new limit marked the start of a “holy war”: the law versus the need for speed.

In 1979, Valentine’s company debuted the Escort, a top-of-the-line consumer radar detector, adding to a newly thriving industry helping drivers to speed with impunity. It would be his life’s work; Valentine released his last detector in 2020, and passed away in 2024 at the age of 74.

The obits honored him as an engineer, entrepreneur, and philanthropist, and “one of the great saviors of speed.” But an alternate story goes like this: Michael Valentine was a criminal mastermind who got rich on technology that enabled thousands of people to get away with breaking the law, and almost certainly contributed to the deaths of innocent people.

In 2022, speeding killed more than 12,000 U.S. road users. Another 3,000 were killed because of distracted driving. These kinds of driver misconduct are among the biggest causes of violent death in the country — and also, legally, some of the most trivial offenses a person can commit. And this seeming contradiction only makes sense when you consider the political power of the people breaking the law, and the businesses profiting by it.

When 'law-abiding' people break the law

Dangerous driving hasn’t always been socially acceptable.

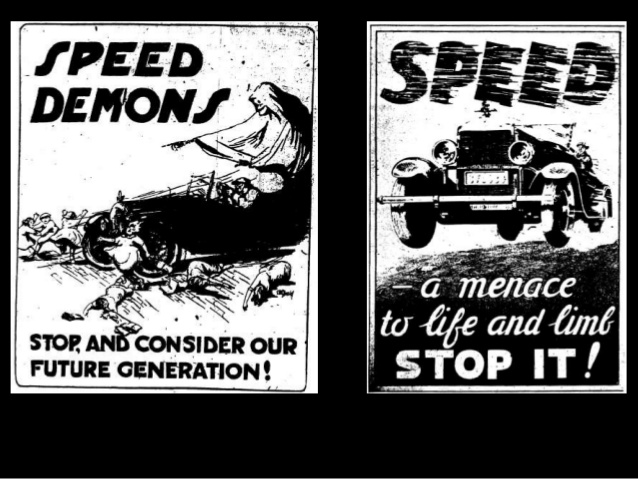

At the turn of the 20th century, when cars were new, almost everybody feared and hated them. Drivers were “murderers” with “gasoline rabies,” their automobiles were ”the modern moloch,” and angry crowds regularly set upon them at crash sites. Back then, pedestrians still had an unquestioned right to be on the entire street, and drivers were believed to be completely at fault if they hurt someone, even if they hadn’t obviously broken the law.

Nonetheless, lawbreaking behind the wheel was common — especially speeding. Going fast was the whole point of a car, and many speed limits, set with pedestrian safety in mind, were hardly faster than the pace of a horse and carriage. But drivers regularly mowed people down even when they tried to follow the rules, and exceeding limits on roadways filled with pedestrians and pushcart vendors resulted in frequent, predictable deaths — disproportionately, the death of children.

This new species of criminality was a challenge for the criminal justice system — because for the first time, the criminals tended to be rich. They were, according to one influential police chief, “some of the community’s best citizens,” and they were often proud and defiant about their crimes. Many believed that if these “law-abiding” people were breaking the law, the problem must be with the law itself.

Critically, the car industry also put its thumb on the scales of justice. New York auto dealers lobbied successfully against a measure to jail speeders, for example, because they obviously didn’t want their customers behind bars. Laws that threatened drivers were a threat to their business. The law bent accordingly.

In 1910, a Denver businessman who killed three people on a reckless “joy ride” got sentenced to one year in jail, and had it commuted after less than six months. A New York doctor, fined five times for speeding, made the news in 1919 when he got ten days in jail for his sixth speeding conviction. These punishments came at a time when car thieves were getting sentenced to years in prison. A cleaner at a garage got two years and four months for borrowing a customer’s car without permission.

The authorities quickly built up new legal structures that segregated drivers’ offenses from the rest of the criminal legal system. Criminal driving, for example, spurred the invention of the ticket, which spared respectable drivers the inconvenience of getting arrested and hauled off like anyone else who broke the law. Judges heard “traffic court” cases separately from other kinds of defendants, and pioneered “educational” sentences, like having to stare at a safety bulletin in a police station for a set length of time, instead of the deterrent punishments imposed on their lessers.

In an era notorious for police giving suspects “the third degree” in interrogation rooms, New York’s police department even enrolled traffic cops in “courtesy classes,” and the “Courtesy Patrol” policed South Dakota’s highways.

Car companies greased the wheels by changing public ideas about streets, vehicles, and pedestrians. “Jaywalking” shifted the responsibility for safety off of cars and drivers and “accidents” transformed crashes into blameless, inevitable bloodshed under the wheels of progress. Scapegoats for dangerous driving — like rogue chauffeurs and “cheap scorchers” in second-hand cars — took the heat off of “ordinary,” gentlemanly drivers.

The killings continued to rise, but outrage ebbed. Dangerous driving largely ceased to be a crime.

'Middle-class folks, just like you and me'

For most of the 20th century, many Americans even trivialized drunk driving, despite its outsize role in the carnage on the roads. But that would abruptly change on May 3rd, 1980, when a drunk driver killed a little girl and ignited a movement.

The driver, Clarence Busch, had a history of drunk driving, including an arrest just a few days prior for a drunken hit-and-run for which the judge hadn’t even suspended his driver’s license. Police told the little girl’s mother, Candace Lightner, that Busch probably wouldn’t face jail time for the killing. Soon after, Lightner founded Mothers Against Drunk Drivers (later renamed Mothers Against Drunk Driving, or MADD.)

Back then, tens of thousands of people were killed each year in alcohol-related crashes, and the US had collectively shrugged it off. But in Ronald Reagan’s tough-on-crime America, Lightner’s simple message about “killer drunks” and innocent victims caught fire, in large part because it absolved car and alcohol companies of responsibility for the carnage and put the blame entirely on individual, criminal drivers.

By contrast, mass media outlets almost completely stopped booking segments with MADD’s rival, Remove Intoxicated Drivers, after the organization came out in favor of restricting alcohol advertising.

“One of MADD's original board members proposed that, as a matter of principle they refuse to accept money from the alcohol industry. He was out-voted on the basis of Lightner's argument that it is not alcohol itself that causes death and injury but rather irresponsible users and abusers of alcohol,” according to a 1988 paper on the rise of the organization.

The efforts of Lightner and her colleagues changed cultural norms on drinking and driving for the better. But some argued that focusing on individual drivers also narrowed the terms of engagement, ignoring the reality that mass drunk driving is inevitable so long as intoxication is customary in social settings and people have to drive.

Rather than opposing the centrality of either drinking or driving in American life, MADD’s worldview arguably hinged on the idea that drunk drivers were an evil few. But there were actually millions of them — and they collectively had political clout.

“Most of the people who slide boozily behind their steering wheels are not criminal types . . . but nice middle-class folks, just like you and me,” wrote a Washington Post columnist in 1981. The social construction of the “killer drunk” was inseparable from that of his everyman twin, the “social drinker,” who sometimes had one too many before driving home, and the everyman could hardly be a criminal.

Big business also stepped forward to protect its customers’ interests (read: profits), with alcohol companies offering up moderate-sounding platitudes like “know your limits. Some even turned to fearmongering about neoprohibitionism when talk turned to decreasing the legal BAC from .10 to .08, which opponents claimed risked ensnaring someone just having a couple drinks with dinner.

As a result, the plight of many drunk drivers mobilized public sympathy, plainly visible in the comparatively gentle sentences typically handed down in American courtrooms. Drunk drivers already feel awful for the harm they caused, apologists argued — did we really need to add to their suffering? Moreover, a conviction could lose someone their job, and a jail sentence would rupture their family; punishing drunk drivers also means punishing their innocent loved ones.

All of these points are true and fair, and also utterly surreal: at a time when mass incarceration was taking off in America, drunk driving had some people talking like prison abolitionists.

A better way

Today, some invoke MADD’s organizing as a model for dealing with distracted driving, the newest cause of mass death on the nation’s roadways. But some would argue that MADD’s success is both overstated and misunderstood.

Alcohol-related fatal crashes accounted for about half of traffic deaths in 1980 and still make up about one third of them today. Moreover, research suggests that decline is mostly thanks to MADD changing cultural norms, rather than increased penalties. (It’s worth noting that while the US is exceptionally punitive overall, drunk drivers are still sentenced more leniently here than in most other rich countries.)

Further, the definition of a “criminal” is socially constructed as much as it is legally defined — and in American culture, people who commit crimes behind the wheel aren't always treated as seriously as other lawbreakers. Advocates have been trying and failing to crack down on drivers’ bad behavior for more than a century, but it’s as hard to criminalize the politically powerful as it is easy to criminalize the weak.

It’s not an accident that manipulating a license plate to dodge tolls is a minor violation, but bending a metrocard to steal a swipe merits a prison sentence; people’s behavior often matters less than the “social category” they come from.

Worse, though crime behind the wheel is treated leniently compared to analogous kinds of wrongdoing, marginalized drivers are still getting the short and pointy end of the stick. Police are far likelier to pull over drivers of color on pretextual stops and search their cars — stops which are more likely to escalate into police violence — and they’re up to 33 percent more likely to ticket Black and brown drivers than a white driver going the same speed. Marginalized motorists are also less likely to be able to pay the ensuing fines, and even traffic enforcement cameras, for all their bias-free promise, have disproportionately ticketed marginalized people, who tend to live places with wider, speed-inducing roads. (The cameras also work overtime deepening the web of police surveillance.) More criminalization means doubling down on a system that offers near-impunity for the many, and a police state for the few.

Happily, there’s an alternative: build a society that’s conducive to good behavior, including building "self-enforcing" roads. That work is already happening, of course; we just can’t let the siren songs of vengeance and deterrence detract from it any longer.

For example, anywhere people might get intoxicated (in other words, everywhere) must be accessible by cheap, efficient and safe transportation. Anything less than that naturalizes or even encourages driving under the influence — and a bar or a stadium with a parking lot is borderline entrapment.

Likewise, every road must be designed in keeping with the speed at which drivers ought to go. A speed limit is nothing but a number, and faced with an open asphalt horizon, many are liable to pull a Michael Valentine. Instead, roads have to have a non-negotiable gauntlet of speed bumps, curb extensions, narrowed lanes, and stop-signed crosswalks. Much like how police only show up after the bad thing has already happened, relying on enforcement after the fact means the road itself has already failed.

Ending mass death on the roads means ending the incentives to behave badly behind the wheel. Cops aren’t the answer. All we need is buses and concrete and a couple million buckets of reflective paint.