Editor's note: After initial publication of this story, Mayor Cherelle Parker reversed her decision and will continue funding for the Zero Fare program for the next fiscal year. We applaud her decision and encourage other cities to learn from the successes of this pilot. But the machinations of the debate in Philadelphia, as described in the story below, remain relevant.

An innovative program to automatically give free transit to low-income Philadelphians could soon come to an abrupt end before officials have even had a chance to measure its full impact — or asses whether it might be a model for other U.S. cities.

Advocates in the City of Brotherly Love are petitioning to save the Zero Fare Pilot, which they believe is the first and only program in the country to automatically enroll a random selection of residents based on their qualifications for other poverty-related benefits programs, like SNAP and Medicaid. From there, the agency simply sent those lottery winners an unlimited fare card in the mail — without even asking them to fill out an application first.

Of the more than 24,000 people who received that golden ticket as part of the initial two-year, $62-million pilot, the regional transit agency, SEPTA, says 64 percent are still riding today — a rate which proponents call "phenomenal" for a program that some feared would struggle to locate riders grappling with housing insecurity, or who might not believe their good fortune and just chuck their free cards in the trash.

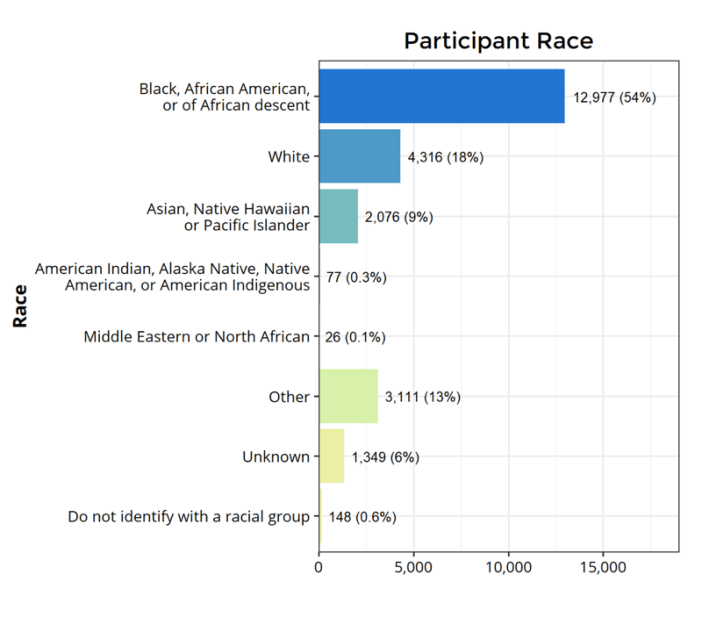

And it's also a testament to the outsized impact that free basic mobility can have on people's lives — particularly if they belong to marginalized groups. A study of the first year of Zero Fare found that 54 percent of enrolled participants were Black, 52 percent were women, and the highest usage came from the city's lowest-income discounts; a study of the second year of the program is still forthcoming, but advocates expect it to show significant benefits.

"This kind of transit access is really critical for the most vulnerable riders," said Morgan Allgrove-Hodges, transit committee co-chair for the urbanist political action committee 5th Square. "The burden of paying for transit is much higher on low income people, who are often dealing with other social and economic disparities. So being able to ease this one disparity can really have outsized benefits for a person's life across the board."

Mayor Cherelle Parker, though, omitted the Zero Fare Pilot from Philadelphia's upcoming budget, arguing that the city had only funded it on a limited-time basis with money from the COVID-era American Rescue Plan Act.

“Those funds have dried out and we have chosen not to continue that pilot,” Tiffany Thurman, chief of staff for Parker’s administration, told WHYY. “But that does not suggest in any way that we do not support SEPTA and are not concerned about their fiscal health.”

For some advocates, though, the popularity of the Zero Fare Pilot exemplifies why cities should invest in providing free (or at least discounted) fares for their poorest riders — something that only 17 of the 50 largest transit agencies in the U.S. do now, a 2021 study found.

Allgrove-Hodges emphasizes that unlike many other communities, Philly's fare-free pilot doesn't require SEPTA to reach into its own fareboxes to cover its costs, allowing the agency to focus on increasing service and recovering the choice riders it lost during the pandemic. And if those city subsidies were retained or expanded, she argues, the agency could make up even more ground — and eventually, lure more paying customers out of the cars.

"Improving the quality of ride for low income riders benefits everybody, and it definitely benefits those choice riders," she added. "By paying for low income riders, this program is also funding SEPTA [in general]. That will have a climate and congestion impact, too."

Moreover, by enrolling SNAP- and Medicaid-eligible riders automatically rather than making them jump through hoops to prove, yet again, that they can't afford the basics, SEPTA has slashed the administrative costs that can make discount-income fare programs more expensive to stand up — all while expanding the pool of people who can actually benefit from them.

"I reviewed a fare program years ago that was [geared towards] senior and disabled riders, and you had to apply in person, which is totally antithetical [to the whole concept]," added Allgrove-Hodges. "Just filling out an application can be a huge burden, and especially for folks that might be working multiple jobs, having to do family care or child care. With the Zero Fare pilot, though, they get their pass, they get the card itself sent directly in the mail, and then they just have to start tapping."

And all that tapping can translate into serious economic benefits for cities. Because using Philadelphia's transit network costs $5 roundtrip for single fares, Allgrove-Hodges says many riders who can't afford multi-ride passes often just stay home when they're short on cash, spending money only within walking or biking distance of their homes. Free transit, though, allows them to spread their shopping to other areas of the city, including downtowns that emptied out during the pandemic.

"Mayor Parker's priority is getting workers back to downtown; she mandated five day, in-person work weeks for city employees," she added. "Well, this program directly facilitates workers coming into downtown. So I'm not really sure what the strategy is behind cutting it, besides just trying to find some extra budget. But this is a budget item that is an economic driver — getting folks to move around the city easier, getting them to work, getting them to points of commerce and points of recreation."

And those recreation benefits shouldn't be underestimated. A 2023 study showed that free transit doesn't significantly impact household earnings for low-income people, but it does "improve individuals’ well-being, and in particular health," which can have downstream economic benefits for public health systems — not to mention individuals' ability to access child care, medical care, or even simple quality time with family and friends.

"Just on my personal soap box, I believe that it's really important that everybody has access to free time and recreation activities," added Allgrove-Hodges. "Just because you are low-income doesn't mean you don't deserve to enjoy some time in a park. [Free] fares help people to have a better quality of life — because life is more than just working 10 hours a day and going to the grocery store and going to the doctor. You should also be allowed to have some fresh air, no matter your economic situation."

With SEPTA facing a dauntingly steep fiscal cliff even as ridership steadily recovers, Allgrove-Hodges says that now is more important than ever for the city to step up and support the agency by extending the Zero Fare program.

And if they can act courageously now, they can set an example of other U.S. cities to increase support for transit in other ways, too, and embrace the long-term benefits it can bring.

"This is money going right into SEPTA's pocket, at a time when they are facing really severe budget issues ... It's not a good time for the city to turn their back on SEPTA and, discourage low income riders from using the system," she added. "Philadelphia is really doing something great here ... to get to lead in this area is something we should be really proud of."