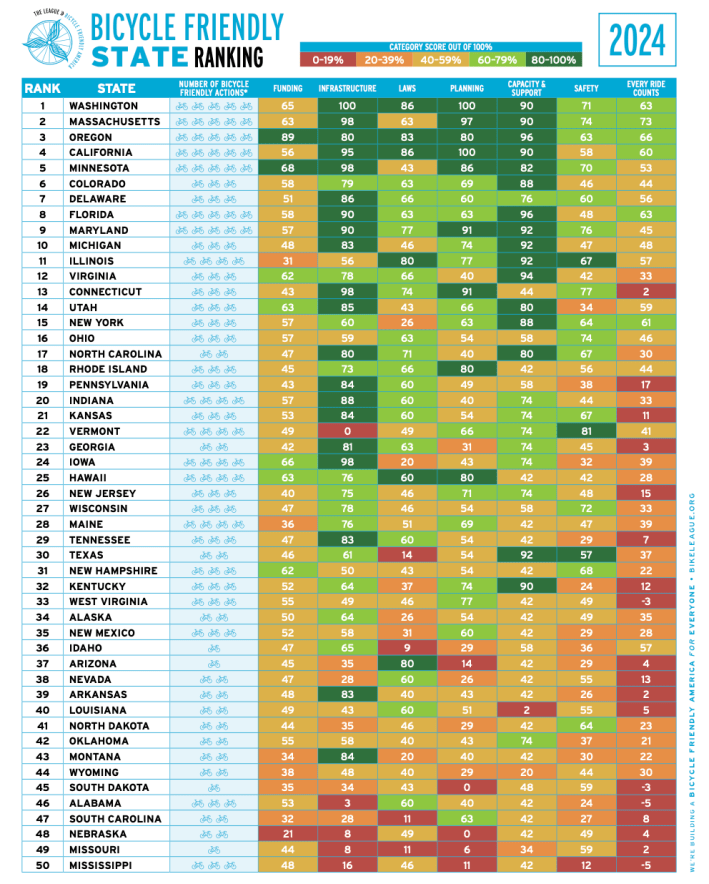

Washington has reclaimed the title of the most bike-friendly state in America — but no state is really doing enough to support people on two wheels, a top advocacy group says.

The Evergreen State has once again ranked first in the League of American Bicyclists' list of Bicycle Friendly States, toppling Massachusetts, which scored the top spot the last time the biennial list was released in 2022. Like then, Oregon, California and Minnesota rounded out the top five.

Meanwhile, Mississippi ranked as the least bike-friendly state in the country, with Missouri, Nebraska, South Carolina and Alabama also sinking to the bottom of the barrel. All five of those states ranked in the bottom 10 last time around, too.

The organization behind the list, though, hopes that advocates will draw on the mountain of data behind the rankings to propel their advocacy in coming years, even if their state rose above the rest.

Because with cycling deaths hitting record numbers nationwide in 2023 — and roads owned by state departments of Transportation disproportionately serving as the site of the carnage — even the best states could be doing a lot more to keep us safe in the saddle.

"We are trying to capture not just outcomes, but effort," explained Ken McLeod, policy director for the League. "We want states to see what other, leading states are doing and be inspired by them — and we also want to make sure that every state has some actionable feedback to improve bicycling."

To deliver that feedback, McLeod and his colleagues combined publicly available data on things like crash rates and funding with a comprehensive survey of DOTs themselves, aimed at understanding how those agencies actually prioritize cyclists in the course of their daily work.

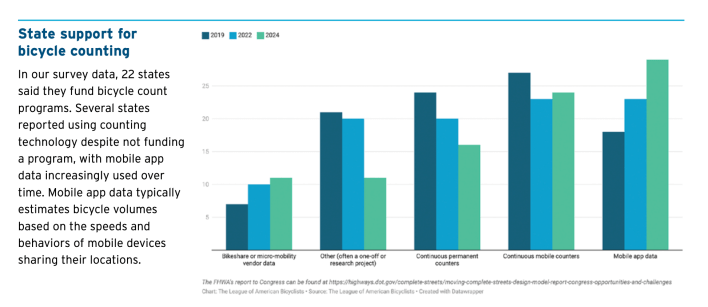

More accurately, though, many states aren't prioritizing active modes — or even counting how many people are getting around outside a car. And without that essential information, it's hard to know whether biking deaths are rising in tandem with, or in spite of, the actual number of riders on the roads.

According to a new question on this year's survey, only 22 states "operate or fund bicycle survey or count programs, which is four fewer than in 2022." McLeod suspects that's because an increasing number of DOTs are outsourcing that data collection to big-data companies, which harvest mobility stats from sources like cell phones — though he questions whether that's wise.

"I mean, if it works, that is great — if we get to the point where we have bicycling and walking quantified in a way that is real," he adds. "But I also worry that continuous permanent counters and continuous mobile counters are more-proven technologies, and [they're] more analogous to how we quantify vehicle traffic. We might miss something if we don't keep doing those more traditional technologies. ... We need states to step up and make bicycle counting and pedestrian counting something that they do on a regular basis as part of their policies, in the same way that we quantify vehicle travel. And we have a lot of work to do there."

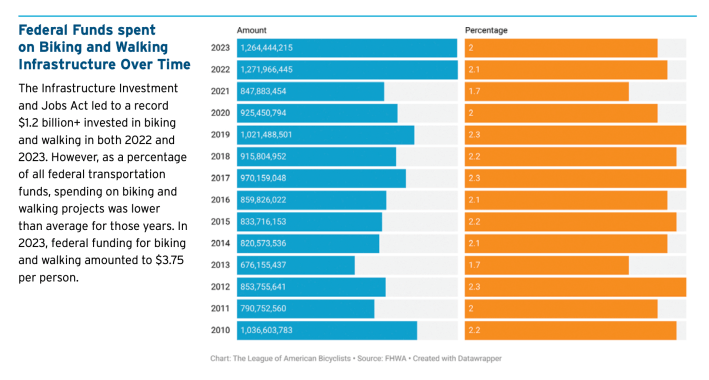

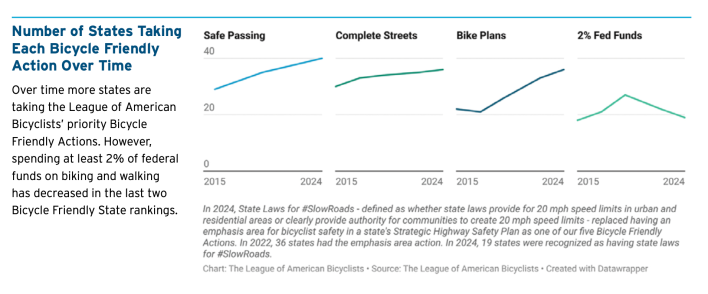

State DOTs also have some work to do when it comes to how they allocate their federal funding across the modes. Despite historic levels of money flowing to biking and walking from the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law, the League found that the percentage of funds that goes to biking and walking is actually decreasing, from an already-pretty-abysmal 2.3 percent "high" in 2017, to a low of just 2.0 percent last year.

"The BIL provided unprecedented resources for biking and walking, and that really is a bright spot to see," added McLeod. "We've had four years where biking and walking spending was over a billion dollars; two of them were the last two years. But unfortunately, the increase in spending on things that aren't biking and walking just increased more — and we haven't seen many states using the flexibility allowed in federal funds to push investments in biking and walking networks even further."

McLeod is careful to note that the League's data doesn't include federal funding from discretionary grant programs like Safe Streets and Roads for All, which largely benefited people outside cars when Secretary Pete Buttigieg was picking the grant winners. With the Trump administration taking the reins of those programs, though, that money could be directed towards drivers — and it's more critical than ever that advocates put pressure on their state officials to resist that trend if it emerges.

He especially urges local advocates to push their states to adopt the League's five top "bike friendly actions," which include spending at least two percent of funds on biking; adopting "Complete Streets" policies and "safe passing" laws; rolling out statewide bicycle plans; and passing policies that support slower streets, like giving cities clear authority to lower limits to 20 mph in places people walk and roll.

More than anything, though, McLeod hopes bike advocates don't forget about state DOTs — and he urges them reach out to the League to learn exactly where they should put pressure on the agencies that are responsible for so many of our worst roadway safety outcomes.

"If you're a local advocate, that's great and that's amazing, but state departments of transportation play a particularly huge role in bicycling," McLeod. "So if you're in, say, Missouri, and your state has [taken just] one of those [Bicycle Friendly] actions — well, you have four potential campaigns right there ... And if your state has a category score that's particularly low, we can tell you what your state did to get that low score — and point towards other high-scoring states [that you can emulate]."