Could ChatGPT Make America More Walkable?

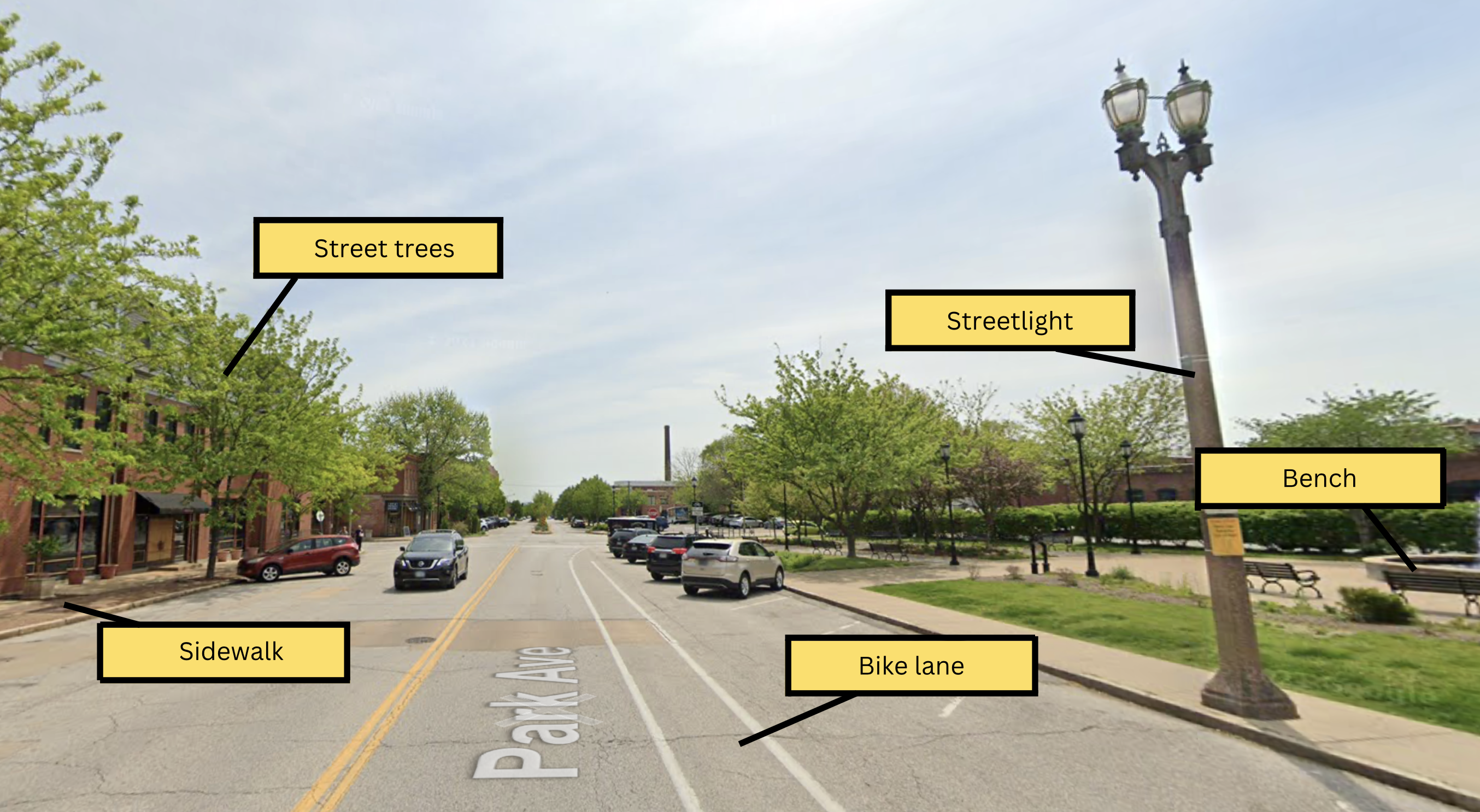

No, generative AI shouldn't plan a whole city — but a new study argues it could help identify gaps in our sidewalk networks, tree canopies, and more.

Stay in touch

Sign up for our free newsletter

More from Streetsblog USA

Tuesday’s Headlines Went the Wrong Way

Multi-lane one-way streets: bad. Single-lane two-way streets: good.

What It Would Take to Map Every Sidewalk In Your State

States and tech companies keep detailed records of virtually every driving lane in America — but not every sidewalk. Until now.

New Calif. Legislation, Backed by Bike Safety Groups, Proposed to Regulate E-Motos/E-Bikes

Electric bicycles are transforming how Californians get around, but the rapid rise of high-powered electric devices has created confusion that puts people at risk,” said Marc T. Vukcevich, Director of State Policy for Streets For All.

The Wonders of Biking in Taiwan

One of San Francisco's most notable urbanists explores Taipei's night markets and bike infrastructure. He wonders: can San Francisco adopt their biking culture?

Why Is the Governor of New York Trying to Make It Easier to Deny Traffic Violence Victims Insurance Payouts?

The governor is still fighting to make it cheaper to drive with a reform that would reduce compensation to some crash victims.

Study: Most Of America’s Paint-Only Bike Paths Are On Our Deadliest Roads

Even worse, most Americans see these terrible lanes and think, "I'd be crazy to ride a bike" — and the cycle continues.